Interviewed and Written by Patrick Mc Gavin 8/09

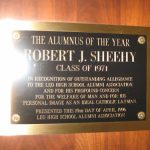

ROBERT J. SHEEHY ’71

A snapshot of Leo High School during the socially convulsive late 1960s, early 1970s: Violence, says one prominent black social commentator and political dissident, is as American as apple pie. America is torn apart by the war in Vietnam, economic volatility, social protest and a new, different civil war occasioned by the civil rights movement. The Chicago novelist Larry Heinemann, who spent a year as infantryman in Vietnam, said upon his return he thought the war had followed him home.

as apple pie. America is torn apart by the war in Vietnam, economic volatility, social protest and a new, different civil war occasioned by the civil rights movement. The Chicago novelist Larry Heinemann, who spent a year as infantryman in Vietnam, said upon his return he thought the war had followed him home.

Leo was both a witness to and a bulwark against the escalating madness. Robert (Bob) J. Sheehy lived about four miles from the school at 79th and California. He entered as a freshman in the fall of 1967. He was a talented receiver on the football team. “The school was so limited in physical resources, the football team had to bus every day to practice at Dan Ryan Woods at 83rd and Western [Avenue]. I lived literally five minutes from there, but after practice, you had to get back on a bus and go back to Leo,” he recalls.

“We came out of practice, back at the school, and we didn’t think of anything just hitchhiking to get home. We didn’t have money for the bus, and hitching for rides was big in those days. Some guys went west, some west north and south and everybody went in different directions. Some days there was a kid, Bobby Rogers, his dad was in the Air Force, and he lived five blocks away. He moved from time to time but he stayed all four years at Leo. He lived in the area, but he drove a car to school. Bobby would pull over and yell at us to get into the car. He’d drive us to Damon or Ashland.”

As the neighborhoods “changed,” from primarily African-American to white, Mr. Sheehy would take the wheel of Mr. Rogers’ car and drive the remainder of the way, just to avoid any further disturbance.

Mr. Sheehy, born in 1953, the third of seven children, five of them girls (his younger brother Jim graduated from Leo in 1977), went to as many Leo football and basketball games during his stint at a grammar school at St. Thomas Moore. His father, also named Robert, attended Leo for two years before finishing at Marmion in Aurora. Mr. Sheehy said his parents probably preferred that he go to the new schools, Brother Rice or St. Laurence, both also run by the Irish Christian Brothers.

“By the time of my freshman year, the demographics had started to change, and most of the kids that I went to grammar school with were going to either Brother Rice or St. Laurence. I had cousins that were going to Leo at the same time, and that definitely sealed it. I played sports when I was in grammar school, and I wanted to play sports at Leo.

First impressions

The dominant memory, Mr. Sheehy says of the first time he visited the school, was nervousness. “My dad drove me to the school that morning. Like anyone, when you go from one level to the next, you’re comfortable in grammar school once you’ve been there for eight years, then you move onto the faces and new places. I used to go to the games, but I really didn’t go to the school that often. When I walked into the school, it seemed massive, but it really wasn’t, concentrating on one block, though it did have four floors, which was unusual.”

Having a Catholic school pedagogical background prepared him for the rigors and discipline of the Christian Brothers. “It wasn’t that much different than the nuns. The nuns in grammar school were just as tough as the Brothers at Leo. By going to a Catholic grammar school, I think I was prepared for what I was about to get into. For the most part, you have almost two different types of Brothers. Some that really intermingled and got along with kids and treated you like a little brother, and there were others for whom you had to walk the line and if you didn’t you were going to pay the price. I think it made all of us better students because if you didn’t do the work, you were going to pay for it. And on the other hand you stayed out of trouble because everything was confined to the school. There was ‘jug,’ and nobody wanted to do that on Saturday. All the Brothers had straps and you’d get it on the hand if you were acting up.

Having a Catholic school pedagogical background prepared him for the rigors and discipline of the Christian Brothers. “It wasn’t that much different than the nuns. The nuns in grammar school were just as tough as the Brothers at Leo. By going to a Catholic grammar school, I think I was prepared for what I was about to get into. For the most part, you have almost two different types of Brothers. Some that really intermingled and got along with kids and treated you like a little brother, and there were others for whom you had to walk the line and if you didn’t you were going to pay the price. I think it made all of us better students because if you didn’t do the work, you were going to pay for it. And on the other hand you stayed out of trouble because everything was confined to the school. There was ‘jug,’ and nobody wanted to do that on Saturday. All the Brothers had straps and you’d get it on the hand if you were acting up.

“I escaped a lot of that. I was a quiet, middle of the road student, not a very good student, but I did the work without getting scared too much. As much as the Brothers made an impression on [earlier generation Leo students] because there were more of them in the school, the lay teachers made as much if not more of an impression on me during my time at Leo.

“I think you could relate to them more better. They could relate to you. In most cases they were just five, six, eight years older than us (though they seemed much older). These were guys who were just out of college and Leo was their first teaching job. They appeared older but they weren’t. To this day, we’re friends with a lot of them. They were tough, they weren’t any easier on us, but you could relate a little easier to them.”

The sixties were as much a state of mind as duration of time. The world was changing dramatically, instantaneously. Vietnam, wrote Michael Herr, is what we had instead of a happy childhood. Chicago was in the middle, of Martin Luther King’s protest marches about equal housing opportunities for blacks to the wild, dangerous actions of the 1968 Democratic National Convention, where protesters and police met in Norman Mailer’s famous phrase, “like armies in the night.” In the spring of 1968, during Mr. Sheehy’s freshman year, Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis, leading to a couple of very tense days around Leo.

“The public schools were led out early out of fear there might be trouble or social disturbances. I remember Calumet was our neighboring school, and the kids were going home [early]. That was probably the most tumultuous time. Rocks were being thrown at the windows. They actually bused us out of school on CTA buses. It was tough for a couple of days. There were problems inside the school in those days, but probably no different than what any school was facing in those times as far as fighting and things. For the most part people got along, and if you didn’t, you weren’t going to stay in school.”

That was probably the most tumultuous time. Rocks were being thrown at the windows. They actually bused us out of school on CTA buses. It was tough for a couple of days. There were problems inside the school in those days, but probably no different than what any school was facing in those times as far as fighting and things. For the most part people got along, and if you didn’t, you weren’t going to stay in school.”

Mr. Sheehy entered Leo a scrawny, tough five-foot, nine-inches. At the start of his time at the school, his reach exceeded his grasp. It was a way that he stood out, in the end.

“I played two sports as a freshman, football and basketball, because in those days you couldn’t play three sports because football in the spring paralleled baseball. (I think it was a couple of years after I got out that they cancelled spring football.) I was small. I was a quarterback coming out of grammar school, and on the freshman team, I was like fourth string. I played a little defense that helped me get on the field, but I didn’t play much as a freshman. My sophomore year, I was probably even lower on the depth chart because we didn’t have [junior varsity] on the varsity at Leo. I was on the team, just going along. The head coach at the time, during spring ball my sophomore year, approached me because I had a growth spurt, jumping up to where I am now, about six-foot, three-inches.

“He basically put it very bluntly: He said, ‘You can stay at quarterback. I won’t move you if you don’t want to, but I don’t think you’ll ever see the field, there are too many guys in front of you. Why don’t you think about going for another position. We need an end.’ That sounded good, so I moved to end.

The position shift changed a great deal for Mr. Sheehy. No longer buried on the bench, he found himself. With each day, he gained confidence and a surer sense of himself. “Everything that spring seemed to work out well for me. Unfortunately one guy ahead of me got hurt, another guy they wanted to play defense more than offense. They moved him over and they tried me at split end my junior year and from that point on it really worked well for me. The current Leo president, Bob Foster, it was his first year of head coaching. My junior year we had a very talented team. I was one of only three juniors that really played that year. The whole [starting] team was mostly seniors. We just had a rough, tough year, hurt by a lot of injuries and things didn’t click how we wanted.

“We were picked to win the South side [division] and challenge for the Catholic League playoffs but we ended up with just a .500 season. As a result, Bob Hanlon had decided to resign. I think the writing was on the wall, coach Hanlon was going to take this last team and that was going to be it. They hired Bob as a teacher and an assistant coach with the idea probably he was going to take the team over.

In the fall of 1970, the pieces fell beautifully into place for Mr. Sheehy and the rest of the team. They found their collective will and discovered their own personality of toughness, grit and solidarity. A team that had little outside support stunned everybody. “We were picked to finish last in the South side division. We lost just one game and played for the Catholic League championship and lost to St. Rita. We got a lot of publicity. In those days the Tribune and Sun-Times reported mostly on the Catholic and Public League teams; the suburban schools received very little print. The fact we kept winning week to week built up a lot of recognition for the team, and none of us were used to it.”

In the fall of 1970, the pieces fell beautifully into place for Mr. Sheehy and the rest of the team. They found their collective will and discovered their own personality of toughness, grit and solidarity. A team that had little outside support stunned everybody. “We were picked to finish last in the South side division. We lost just one game and played for the Catholic League championship and lost to St. Rita. We got a lot of publicity. In those days the Tribune and Sun-Times reported mostly on the Catholic and Public League teams; the suburban schools received very little print. The fact we kept winning week to week built up a lot of recognition for the team, and none of us were used to it.”

Leo’s success and Mr. Sheehy’s natural ability had other immediate implications. Major universities were suddenly inquiring about him and coming to watch him play. He was being recruited for a college scholarship. “There were a bunch of schools interested in me: Illinois, Wisconsin, Notre Dame for a while, Purdue obviously, as well as interest from Northern Illinois, Wichita State. I did make a trip to Northern Illinois, I had made a trip to Illinois, two to Purdue; Notre Dame recruited me early on, then dropped off. Just before the time came that you had to commit, George Kelly, the linebackers’ coach at Notre Dame, came to one of our basketball practice. I talked to him and he said they wanted me. I had a heart to heart talk with Bob Foster, and he pretty much said what happened was they were going after another kid and they didn’t get him, and I was on their [secondary] list and they moved me up.

“Coach Foster said Illinois and Purdue wanted me from the start. He said, ‘My only advice is go where somebody really wants you.’ That helped me a lot. My parents didn’t really care where I went, they were just happy that I had the opportunity to go anywhere, but they liked me to stay local, so that if I ever did play, they wouldn’t have to travel great distances to come watch me play and not have to go to Wichita State. It was a fun experience, the recruiting process. I ended up taking the scholarship to Purdue.

“Sports at Leo were good to me,” he says.

“I think it was just because I loved sports that I was part of [the basketball team]. I started as a sophomore on JV team. Then junior year I didn’t get in at all on the basketball team. It was fun being on the team. My senior year, I played halfway through the year and the colleges recruiting me for football wanted me to come visit the school on weekends. I was making a hard time where I wanted to go, so I ended up quitting probably halfway or three-quarters through the year. Then I end up playing baseball my senior year. There were no conflicts with football, and I had fun because I hadn’t played organized baseball in three years. I was the catcher.

“We didn’t have a really good baseball team. There was a Catholic League all-star game between the South and North side. The game was at Comiskey Park. They had a requirement that two kids from each team had to be picked, so I was picked more or less not on my ability but because they had have two [from Leo]. I also tried out track for one year and I lasted about a month. Running was not my favorite [activity], but I did learn how to properly run in that period. Leo track used to run on the third floor, that was the indoor track facility. If you’d go up there you had to be careful nobody came out of the classroom when they were doing sprints or you’d get killed.”

two kids from each team had to be picked, so I was picked more or less not on my ability but because they had have two [from Leo]. I also tried out track for one year and I lasted about a month. Running was not my favorite [activity], but I did learn how to properly run in that period. Leo track used to run on the third floor, that was the indoor track facility. If you’d go up there you had to be careful nobody came out of the classroom when they were doing sprints or you’d get killed.”

Socially, personally, Mr. Sheehy found his own métier. Leo was the center of his world. He had friends from his own neighborhood at St. Thomas Moore, but he also branched out and cultivated new friendships, with people black and white. If life outside the school was almost hallucinatory, Leo was a stabilizing place. He was, by his own admission, not a great student. He was no fan of the geometry or trigonometry courses, but he liked and did well in English, history and the school’s business curriculum. “My sophomore year I worked at Beverly Country club in the snack shop. My freshman year I worked at Beverly Woods restaurant as a dishwasher. My senior year out of high school all the way through college, I worked at the Wilbur Company Burial Vault.”

By the time of Mr. Sheehy’s graduation, in the spring of 1971, Vietnam still raged, but the Nixon Administration had begun a gradual policy of de-emphasizing American combat units. “In those days you had the lottery, and I had a high number, and I didn’t end up going, but a lot of my friends did. At the tail end of that in my senior year, they were tamping down. They had the lottery, but they only took about 100 names.”

College life

The West Lafayette, Indiana campus of Purdue University marked the next stage of Mr. Sheehy’s personal evolution. He traded the almost fractious, musical rhythms of urban life for the quieter, more contemplative rural culture. University culture was also quietly changing, moving from the militant, confrontational tactics of the Sixties to the more culturally conservative milieu of Nixon’s silent majority. “It was very interesting. Even back then, you went to Illinois and they had bars on campus and a lot of fun things to do. At Purdue, they had a Pizza Hut on campus, and it was more of a family restaurant. That’s where you went to drink; they had strict rules. If you went there to drink, you had to eat. Purdue was oriented to fraternity and sororities. We were pledging to a fraternity, but we opted out because it was too hard with football and academics.”

Even so, he discovered his own culture shock. “My freshman year, in the dorm, you’d see these friendly, quiet kids that were leaving at five in the morning, and they’d come back at nine o’clock. Nobody ever questioned where they were going or what they were doing. It turned out they were farmers, and these kids had to go home and still do their chores. Their parents wanted them to have the experience of college and still live on campus. That didn’t mean they didn’t have to go back home and work the farm. We were exposed to a wholly different lifestyle. Purdue was a good campus and a good school.”

Even so, he discovered his own culture shock. “My freshman year, in the dorm, you’d see these friendly, quiet kids that were leaving at five in the morning, and they’d come back at nine o’clock. Nobody ever questioned where they were going or what they were doing. It turned out they were farmers, and these kids had to go home and still do their chores. Their parents wanted them to have the experience of college and still live on campus. That didn’t mean they didn’t have to go back home and work the farm. We were exposed to a wholly different lifestyle. Purdue was a good campus and a good school.”

Making the transition to big-time college football stood its own considerable challenges. It was not just a game; it was a serious business. “I was on the team. I was on college scholarship all four years. I didn’t get into the games very much. What happened was when I was a sophomore, the coach that recruited me was fired at the end of my sophomore year and I was basically second string then with a senior ahead of me.

“It was looking promising that I’d get to play a lot more the following year. Alex Agase came over from Northwestern to coach Purdue. Within a week before we were going to play Wisconsin, I got demoted. Agase basically said, ‘This year for me is a wash. I’m just looking forward to get my [own recruited players in].’ He was moving in a lot of freshmen behind a lot of us juniors. They had four or five years and if they didn’t have a winning team, they’d usually get fired. So it worked out differently.”

Unorthodox family business

Mr. Sheehy studied industrial management and business at Purdue. His childhood sweetheart, Kathy, whom he’d eventually marry and have a family with, was attending Quincy College in central Illinois. If he received a stark lesson in the politics of major college football, Mr. Sheehy primed himself for the next stage of his life.

Mr. Sheehy was born into an interesting, not to say unorthodox family business. His paternal grandfather, Roger Sheehy, founded the family’s first funeral home, at 76th and Halsted, in 1913. “My grandfather was a postal carrier. He liked it, but in those days, if you wanted to be a funeral director, you went down to City Hall and you filled out a license and they gave you your certificate. He started in the business and went along very well for a number of years. In those years you’d wake out of a house, so you didn’t have the capital expenditure you do in a building.

in 1913. “My grandfather was a postal carrier. He liked it, but in those days, if you wanted to be a funeral director, you went down to City Hall and you filled out a license and they gave you your certificate. He started in the business and went along very well for a number of years. In those years you’d wake out of a house, so you didn’t have the capital expenditure you do in a building.

“For a number of years they did that until the forties when they determined it was not a healthy option, emotionally for instance of exposing young children to that. That’s when funeral directors started looking for properties and opening up chapels. The home at 76th and Halsted was the first one they opened and they sold it in the early sixties.”

Mr. Sheehy’s father and two uncles maintained the family business. Interestingly, Mr. Sheehy says his own father took a parallel track with his grandfather. “He started out like my grandfather in the postal business. He was not going to go into the [funeral home] business, but then he injured his back and he could not continue in that line of work,” he says. In 1975, following his graduation from Purdue, Mr. Sheehy had several career options. “Coming out of high school I didn’t know if I wanted to go into the business, that was the last thing on my mind. So that’s why I went to Purdue,” he says.

He did the necessary post-graduate work at Worsham College, a school of mortuary science then located in the Loop. “When I got out of college, my father said, ‘Here’s what I suggest you do. Work here for six months or a year and then decide if that’s what you want to do and go to school and pursue it.’

“I worked here and I really liked it. I thought, ‘This is what I want to do.’ The worst thing in any field is to be forced into doing something you don’t want to do. Even if you’re making a lot of money, it’s a tough road.”

By the late-70s, the family was operating four different funeral homes on the south side. The company principals were his father, his uncle and a close family associate. “Our generation was coming into the business. My cousins were older and they had been in the business. Andy, the associate, also had a son and he was ready to get into the business. We could see the writing on the wall, and there were too many people in the business to handle all of this,” he says.

By the late-70s, the family was operating four different funeral homes on the south side. The company principals were his father, his uncle and a close family associate. “Our generation was coming into the business. My cousins were older and they had been in the business. Andy, the associate, also had a son and he was ready to get into the business. We could see the writing on the wall, and there were too many people in the business to handle all of this,” he says.

The family split the business four ways, with each segment taking ownership of a particular funeral home. In 1995, Mr. Sheehy and his father (eventually joined by his brother James) shifted their operation to Orland Park. So they opted all to take their own funeral home. My uncle took 127th; my dad, my brother and I took 79th Street; Andy took the Pulaski; my brother and I brought the company to this location, in Orland Park, in 1995. Today, Mr. Sheehy is the president of Robert J. Sheehy & Sons. The company operates funeral homes in Orland Park and Burbank. Mr. Sheehy directs a staff of some 30 employees, one-third of them full-time.

Mr. Sheehy is a witness to the intricate, subtle changes in the business. “In the past everything was more predictable, even traditional. When somebody passed away, it was a two-night wake, you had a Hearst, a limousine and a flower cart. Now, people are looking for different things and how they handle it. They still wake, but they may want a memorial service or a cremation. Everything has changed, just like any industry, so you have to move along to what people want. That’s not always easy. Once you’ve been in a business for a certain period of time, you get to knowing what to expect and that not the case today. We tell our people, ‘Expect the unexpected.’”

It is an emotionally intricate business that is a powerful and sometimes painful reminder of the fragility of life. “We just had a young man, 21 years old, who died in a motorcycle accident. I have a son that’s 20. All the way through, you’re raising your kids and you hear these terrible stories and the families are right in front of you going through this horrific time. You also become very humble and thankful for what you have because you see some families have to struggle. It keeps you more level headed.”

Mr. Sheehy and his wife Kathy have two college-aged sons. He is a member of the Leo Hall of Fame, a past president of the alumni association and a former president of the high school advisory board. He is also on the board of directors of the State Bank of Countryside and employee trustee of Teamster, local number 727.

Leo laid the groundwork, a young man who experienced the great social and cultural tumult of the times and found his own voice. “You learned to grow up in those four years, and you learn to respect each other. I’m glad I went to school with kids from the inner city. I saw a whole different life than growing up at 79th and California was so much different than the kids growing up at 79th and Halsted. Going to a school that was racially mixed I think was a healthy thing for anybody, especially in those days.

“I think a lot of my classmates are some of my best friends to this day. We’ve all stayed close. That’s what I think Leo is all about. I’ve always run into kids of my generation or younger who went to public schools and they say they are jealous of the fact they’re still close with their high school friends but they don’t have that.”

Speak Your Mind