Interviewed and Written by Patrick Mc Gavin 8/08, Edited by Larry Lynch ’75

BENJAMIN DEBERRY ’64

The French existentialist Albert Camus famously said in order to exist, man must rebel. The act of rebellion takes many forms, styles and iterations: against church, state, or man’s inhumanity. The through point is always the same: life is ultimately governed by willingness, need, to try something unexplored or unexpected.

Nearly five decades ago, Benjamin H. DeBerry confronted a momentous decision of selecting his high school. Every second of the hour, we are confronted by choice and decision. Life has a physical relationship and reaction to each of those; they splinter and move, most prominently referred to as a form of dominos in which a single act carries cascading and far-reaching implications.

Nearly five decades ago, Benjamin H. DeBerry confronted a momentous decision of selecting his high school. Every second of the hour, we are confronted by choice and decision. Life has a physical relationship and reaction to each of those; they splinter and move, most prominently referred to as a form of dominos in which a single act carries cascading and far-reaching implications.

Part of that is also having the fortitude and the drive to be different and take on all challenges. In the fall of 1960, Ben DeBerry decided to become part of history by becoming a member of the first group of black students to attend the historically all-white Leo High.

Ben grew up on the South Side, at 94th and Harvard, near State Street. He was the youngest of eight children. His parents, both Mississippians, were part of the greatest mass movement in our country’s history, the estimated five million black Southerners that moved from the rural South to the urban North, in what the cultural historian and journalist Nicholas Leman called “The Promised Land,” between the years of 1940 and 1970.

“My father started off as a foundry worker,” Ben says. “One of his colleagues, his mentor, progressed through the aluminum foundries and my dad followed him. He became a foundry foreman and later became a superintendent with the Curto-Ligonier company.”

Ben’s two older sisters became the first in the family to attend a Catholic high school, St. Michaels on the North Side. They were the family trailblazers. It set up a basic decision for Ben. His choice came down to two schools: Mendel or Leo. Ben was part of an emerging parish, St. Thaddeus, located a couple of blocks from his house. His parish priest told him Leo was integrating its student body. “He thought it would be a good experience for me,” Ben says.

In The Promised Land, Leman sketches the social dynamics of the city: “The South Side is a long sweep of neighborhoods roughly in the shape of an isosceles triangle. The sharp northern point of the triangle is at Twelfth Street, where the bus and train stations were, and the two long sides extend southward for nearly fifteen miles until they reach the southern border of the city.”

“In my neighborhood there was a very renowned jazz club, the Esquire Lounge, where there were singers,” he says. “Farther north, there were three or four places that were world famous for having blues and jazz singers. You’d go into these clubs and see blacks and whites. In my neighborhood, mostly black businessmen owned the stores. A Jewish entrepreneur owned the larger supermarket. The other white people you saw coming into the neighborhood were insurance salesman.”

New generation at Leo

As the new generation of Southern blacks arrived on the South Side, the black middle class sought to move either west or north into previously all-white neighborhoods. Schools like Leo had to adapt to the new realities. “I can’t say I was colorblind but very color insensitive,” Mr. DeBerry says. “I think [Leo] was my first real awakening to what racism was really about. In particular I was aware how the influence that an absence of knowledge or ignorance plays in racism. It probably never occurred to many of the individuals that my aspirations and my parents’ aspirations for me was exactly the same as their parents.”

neighborhoods. Schools like Leo had to adapt to the new realities. “I can’t say I was colorblind but very color insensitive,” Mr. DeBerry says. “I think [Leo] was my first real awakening to what racism was really about. In particular I was aware how the influence that an absence of knowledge or ignorance plays in racism. It probably never occurred to many of the individuals that my aspirations and my parents’ aspirations for me was exactly the same as their parents.”

Mr. DeBerry says the freshman class of 1960 had about twenty African-American students. “It was a very slow influx of African-Americans at Leo,” he says. “In all candor you’d probably hear different degrees of receptivity that blacks had at Leo.” He entered with a trepidation of not knowing what to expect or how he’d respond to an environment that was radically different for everybody, both the new group of black students and the school’s existent student body whose social and group interaction with black peers extended from the limited to the nonexistent.

Mr. Berry responded with the temperament and sensibility of a social or forensic scientist. He sought out ways to understand others, their differences, fears, what he calls the “perceptual bias that we are all victimized by,” and he worked diligently to turn it all in on itself. He tried to imagine being part of their world. “To survive at Leo, I think I had to develop the coping skills that enabled me to help people see I was a person, not just a black person. I think some were more accomplished at that than others,” he says.

He attached himself to groups and institutions, but he directed his energies and outlets that expressed his individuality. He was active in Boy Scouts until halfway through Leo. He was proved his mettle early, developing a profound and steadfast attraction to work. It gave him an outlet, a solidity that enabled him to see and understand situations different than his own. He reached Leo High by taking two buses, the 95th Street bus to Halsted, and the Halsted Bus to 79th. He’d walk the rest to Leo campus at Sangamon.

Mr. DeBerry also worked an evening paper route that also helped him instill discipline and repetition in his daily routines. His subscribers rarely minded if the paper was late, he says. They knew he was active at Leo with classes and sports. “They became more friends than customers,” he says. “I ended up getting more business from them doing odds and ends, doing their floors, their windows, than I did on the paper route,” he says. To make extra money, he worked as a janitor at the parish. He never looked down on anything.

Despite the profound social changes and altered racial demographics of the South Side, Chicago remained an intensely segregated place. Mr. DeBerry’s neighborhood remained exclusively black. He says he was too young to appreciate it at the time, but in his daily trek to his grammar school, Holy Name of Mary, in Morgan Park, near 112th Street, Mr. DeBerry estimated he passed probably fifteen to twenty Catholic schools. As he got older, the experience burned in him how deeply was Chicago segregated socially and culturally. There remained dividing lines, demarcation zones, in which blacks were simply not welcome.

“I think segregation was very real, and there were very clearly lines or geographic areas that represented borders, places that essentially said: ‘This is where black growth stops.’ Going west of Halsted was not accepted. Going west of Halsted anywhere on the South Side between 71st and 111th just didn’t happen,” he says. If you were black and went as far west as Vincennes, it was a racial provocation that was an invitation to a fight.

It was a time of great polarities. There were fights, but they tended to be settled exclusively fists. “They were not shooting fights,” Mr. DeBerry says. Drugs were scarce to nonexistent; violent crime was also very rare.

Athletics breach social gap

The breakthrough for Mr. DeBerry was sport. Like much of the American social fabric, the ideal of competition and team had a strange and peculiar way of eliminating many of those differences. “Leo was a toughening experience,” he says. “I think as an athlete my experience was somewhat not as difficult as some of the other African-Americans. As an athlete I had a chance to meet an awful lot of guys on a team basis, which often tends to break down barriers that just aren’t naturally broken down.”

In grammar school Mr. DeBerry played competitive football and baseball. He showed particularly skills and talent in football. He essentially invented his own position, a quarterback who lined up exclusively in what today is called the “shotgun,” off the line of scrimmage, or a short punt formation. He walked into Leo secure in the knowledge that he’d be the freshman team’s starting quarterback. It never happened.

He was dropped from the team. The memory still stings. “It was my first time ever having been cut from something,” he says. “By the way, there was no reason I should have been cut, not from a speed perspective or anything else. I think the coach had predetermined who he wanted at some positions from the grammar school teams in the area, and I didn’t fit that profile and I was cut.”

He was dropped from the team. The memory still stings. “It was my first time ever having been cut from something,” he says. “By the way, there was no reason I should have been cut, not from a speed perspective or anything else. I think the coach had predetermined who he wanted at some positions from the grammar school teams in the area, and I didn’t fit that profile and I was cut.”

He was hurt and upset, but not bitter. True to his nature, he found something else. At the invitation of Jim Arneberg, he put his energies into a different sport. He’d never played organized basketball. He was quick, had good instincts and was a good jumper. What he was not was overly tall. He played four years in the lightweight division, his final two years on the varsity program. He would not be prevented this time and he started every game. Players were not grouped by ability but height: players over five-feet, eight-inches played heavyweight; those who did not reach that height played lightweight.

“Lightweight was just as popular,” he says. His success pushed him to go out for the track team his freshman year in the spring of 1961. He experienced instant success and was elevated to the varsity program. His specialties were the quarter and half mile, what was then the 440 yard and 880 yard dash. “Running varsity as a sophomore enabled me to establish my reputation as a good athlete and a promising athlete as a basketball player. That was probably the key factors in making Leo a much more rewarding experience.”

Not wanting to repeat his disappointing football experience, he was the first black athlete on the cross country program in the fall of 1961. The distance covered was about 2.1 miles. The team practiced at Dan Ryan Woods. “Cross country was three of my most interesting years at Leo,” Mr. DeBerry says. “There was one African guy at Brother Rice, an exchange student. I got to meet other guys, not African-Americans, guys who were track enthusiasts and we developed these common bonds.”

Classroom was liberating

If Mr. DeBerry found relief and ease on the courts and fields, he also found himself increasingly drawn to the power, imagination and inventive capabilities of his teachers at Leo. The experience of being taught by the religiously inclined helped reinforce and deepen his brand of spirituality. “I remember some of the conversations I had with the select Brothers about their vocational training and about their missions,” he says. More than 45 years later, he still holds rapt memories of the humor and discipline of Brother Hennessy.

Perhaps his favorite was the eccentric nature and emotional and highly unconventional work of Brother Sloan. “He was a volatile character,” Mr. DeBerry says. “He was renowned for his literal interpretations of English literature. “He’d act out Shakespeare and always did something that resulted in breaking a window or tripping and we’d all laugh. The football and basketball coach Jim Arneberg impressed Ben open, plain, straightforward style that was refreshingly direct. “He was receptive, principled and a picture of competitive fire who had great aspirations to help Leo men become better than he was.”

At Leo, Ben harnessed a talent and skill for working. It gave him an outlet for his energies and provided a foundation that would shape the rest of his professional life. The school was very helpful him land his first job selling records at a store on Halsted. That served a prelude to an even better position at the gilded Frank’s Department Store. He worked as a suit salesman at the store. The job provided an invaluable service in direct contact with clientele. “I don’t think that would have happened had I gone to another school,” he says.

The jobs were crucial in helping him defray the costs of transportation and tuition at the school. The economic stimulus played a crucial role in his independence, a quality that proved necessary very early in his life. “Leo helped precipitate that and get me to understand about customer service and client satisfaction,” he says. The school also helped set up his first significant paying job, a salesman job at Lampkin Leather Goods. “Bob Lampkin had been the basketball coach at the school at one point. They used to make the leather grips. The camaraderie that you develop at a school like Leo, the rich tradition that you begin to inherit, were all very important in shaping any success that I’ve had in life,” Mr. DeBerry says.

The expert combination of school, education, work and athletics helped transform his life. He received a track scholarship to attend DePaul University. “I grew to have a high regard for Leo by the time I was a sophomore or junior,” he says. He developed an affinity for Irish-Americans. He recognized a shared or dual sense of historical destiny and cultural similarities and elective affinities between the plight of the Irish and their large-scale arrival in America and that of African-Americans. “If you could transcend for the moment that you were African-American, the only memories I have [for Leo] are positive.”

He was first male in his family to attend college. He inquired about Notre Dame. The DePaul scholarship offer propelled his decision to remain in Chicago. His personal circumstances altered everything. One summer in high school, a group of friends asked him to drive to a party. He met a young woman named Hellen, a student at Hyde Park. “I thought she was the belle of the ball,” he says. At DePaul he entered the school’s liberal arts program. By the time he entered college, the civil rights movement and the growing student demonstrations against escalated American military involvement in Vietnam transformed American cultural and social life.

Ben’s political revolt took subtle forms, like joining the Black Student Union and taking part in a student symbolic seizure of the ROTC building. He married in 1966 at age 19. The couple’s daughter, Benet, was born in 1967. Her birth and Ben’s growing responsibilities necessitated a cool head and a studied approach. He worked a series of full-time jobs during the day while pursuing his education at night. He shifted to the school’s business program, and he specialized in marketing and sales. He worked a variety of jobs—a factory operator at 3M Company and a series of apparel sales jobs that developed out of his experience at Leo at Frank’s Department Store. He rose to the level of manager in custom services for Illinois Bell.

His corporate kicked off in earnest once he obtained his bachelor’s degree from DePaul in 1970. He began as a salesman for Inland Containers, a division of Inland Steel. He worked there for 11 years. After the division was sold, Mr. DeBerry joined the Dutch manufacturing concern, Van Leer. He worked there for nine years, rising to the level of vice president of sales and marketing. Having developed his business acumen for twenty years, Ben took the leap into entrepreneurial investment. He bought a controlling interest in Dock’s Seafood, the South Side-based fast food chain. He developed the brand and pushed its revenues higher each year. After seven years in the company, achieving the level of CEO, he sold his interest to a private equity firm.

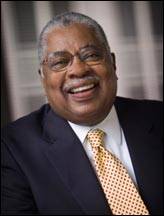

In 2000 Mr. DeBerry instituted the next phase of his professional life. His next challenge was mastering the complex field of executive search. The profession helps companies to identity, assess, recruit and attract top executive talent in strategically growing their practice areas. Ben worked for seven years in A.T. Kearney’s Chicago office. On July 9, 2007, Mr. DeBerry was named the president of the Carlyle Group Ltd. Working out the 21st floor of the company’s Michigan Avenue office, he oversees a firm with seven partners in fields of consumer, industrial, real estate and professional management.

identity, assess, recruit and attract top executive talent in strategically growing their practice areas. Ben worked for seven years in A.T. Kearney’s Chicago office. On July 9, 2007, Mr. DeBerry was named the president of the Carlyle Group Ltd. Working out the 21st floor of the company’s Michigan Avenue office, he oversees a firm with seven partners in fields of consumer, industrial, real estate and professional management.

After living for many years in Flossmoor, Mr. DeBerry and his wife Hellen live in Chicago. They have two sons, Ben, the general counsel for Ziegler and Brandon, a 1998 Leo High alumnus, who recently graduated from the law school of Notre Dame. Their daughter, Benet, is a professor at the University of Illinois-Chicago. The DeBerrys have four grandchildren.

Ben ascribes a significant part of his professional success to his formative years as a student and athlete at Leo. “To be able to succeed at a team environment was very important. You can’t underestimate that. I think understanding people’s differences and being able to focus energies and efforts to achieve goals, that was clearly birthed at Leo High School,” he says.

He served on the school board for many years. By his own admission, his time at Leo was alternately bruising, conflicted, tense and fraught with challenges and obstacles that he had to surmount. He never backed down. He confronted classmates when he thought their behavior crossed the line. He stared down conventional beliefs and attitudes of the time and sought to educate the misinformed. “I emphasize some of my best friends are from Leo, so it must have worked out in the end,” he says.

His parents’ neighbors marveled at the sight of so many young men, black and white that congregated at the family’s house decked in white dinner jackets, for a graduation party that remained buzzed about for years to come. “[Leo] helped me to become a better person, a better man and a better black man,” he says.

“I became very confidant of who I was by being a minority in an environment that was really not used to seeing minorities.” He left Leo, but the school remains firmly etched to his identity.

“It is very common in my world to meet a Leo man or meet somebody from Mount Carmel who wanted to be a Leo man.”

Ben was one of the classiest guys of the class of ’64

Golfed with ben in the Inland Steel golf league back in mid 70’s what a great guy and a true Leo man!