Interviewed and Written by Patrick Mc Gavin 1/11

CURTIS COOPER ’75

Every era has its wonders and aura of innate possibilities. Coming of age on the South side of Chicago in the late nineteen-sixties and early seventies is tinged with the contradictory and the eventful. It was a time of discord and rancor but also solidarity and trust. The extreme conformity and social hierarchies of the previous decade turned into something looser and more spontaneous.

and the eventful. It was a time of discord and rancor but also solidarity and trust. The extreme conformity and social hierarchies of the previous decade turned into something looser and more spontaneous.

Change was everywhere, the ground shook and the country was clearly divided. It was a time of violence and public rupture, of assassinations, protests and intimate, televised horror. A young boy like Curtis Cooper was endowed with freedom and jauntiness to make his own mark. He personified a time and place, of not necessarily fitting in but standing out. It was done through different registers.

He was born, in 1957. He was blessed with God-given talents, a kind of grace of movement that manifested itself quite early in his life. In French, the word histoire refers both to history and story. This is his narrative, potent and real.

Origins

“My grandparents lived in Mississippi,” he begins. “My mother, Thelma, was originally from Chicago. My mother went to Phillips High School [at 244 E. Pershing Road]. My stepfather, Rudy Cooper, adopted me. I have three sisters and two brothers. One of my sisters died. I was in the middle. We were from the South side. When I was a tot, I lived in Hyde Park. We moved further south to the Roseland area around 111th and Yale.”

Education was critically important in his family. “I went to all Catholic schools. I started off at Holy Angels. I went to St. Ambrose grade school. I went to St. Helena of the Cross [at 10115 South Parnell Avenue]. I have three sisters and two brothers. One of my sisters died. I was in the middle. My oldest brother Norman went to Hales. My older sister went to Fenger. My youngest brother and my younger two sisters went to Corliss. My sister went to Northern Illinois and so did my youngest brother. My younger sister went to Western Illinois.”

Education was critically important in his family. “I went to all Catholic schools. I started off at Holy Angels. I went to St. Ambrose grade school. I went to St. Helena of the Cross [at 10115 South Parnell Avenue]. I have three sisters and two brothers. One of my sisters died. I was in the middle. My oldest brother Norman went to Hales. My older sister went to Fenger. My youngest brother and my younger two sisters went to Corliss. My sister went to Northern Illinois and so did my youngest brother. My younger sister went to Western Illinois.”

As a young kid, Curtis showed tremendous aptitude with a ball in his hands. St. Helena had a storied sports background. “One of the interesting things about my Catholic grade school, St. Helena, is that Dick Butkus graduated from there. At our football banquet when I was in seventh grade, Butkus, Gale Sayers, and the sportswriter Bill Gleason came to talk. That was pretty neat. That’s a good memory I have. We had a really good team when I was in seventh grade. But the next year we suddenly didn’t have a team. The school said it did not raise enough money to provide uniforms for the players.

“Bob Foster, who was the coach at Leo, remembered seeing me playing in seventh grade. The other schools, Brother Rice and Mendel, said, ‘We can’t offer you a scholarship.’ Bob Foster and other people from Leo came to our house. My mom said, ‘You‘re going to Leo.’ There were no regrets there. It worked out really well.

In Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, a British aristocrat, down on his luck, is asked how he lost all of his money. “Two ways,” he says. “Gradually and then suddenly.” Change was both volatile and insidious. Sometimes it clamored down, and other times it was quiet and almost unobtrusive. “When you’re young, you don’t assume and think about that stuff,” Curtis said.

volatile and insidious. Sometimes it clamored down, and other times it was quiet and almost unobtrusive. “When you’re young, you don’t assume and think about that stuff,” Curtis said.

You’re not into politics. At that time the area where we lived was definitely pretty segregated. We moved out [to Roseland] in 1967. It was actually pretty integrated and then a couple of years later it was all African-American. When we moved there, the school was majority white and by the time I graduated from St. Helena it was majority African-American.

“For us, growing up, a typical evening was going to the park and just playing. Whether it was basketball, baseball or touch football. That just consumed a lot of our time. We had a couple of different parks that we went to all the time, one at 104th and Wallace and Princeton Park, on 96th, near Chicago State. Between those two parks is where we spent a lot of time. Every park had a basketball court, a baseball diamond, and of course, you just made your own football field.

“At the same time, we weren’t naïve about what we happening around us. There were some gang bangers, people involved in gangs, but they didn’t mess with the athletes. It was part of the good parenting we had. They kept us grounded and focused studies and sports.”

Leo beckons

“I enrolled at Leo in the fall of 1971. Actually, I had to go summer school, so my first taste of Leo was that summer of 1971. I took a couple of classes during the summer. My [early] memory was the Christian Brothers. They obviously had a reputation, but with me, they were pretty cool. You have to understand I had a Catholic education, so I went from nuns to Christian Brothers, and it wasn‘t really that big of a difference.

“At Leo, there were a lot of activities and sports to do. There was swimming, touch football and three or four other sports to participate in. I remember losing by one point the title of athlete of the summer. The reason the other guy beat me was because he swam better.

“At Leo, there were a lot of activities and sports to do. There was swimming, touch football and three or four other sports to participate in. I remember losing by one point the title of athlete of the summer. The reason the other guy beat me was because he swam better.

“You couldn’t play varsity as a freshman, but I was the on the varsity for three years. Sports in general were a very big deal back then. It was pretty much accepted if you were good in sports, you were well respected. I was also a good student, averaged a B, and I was on the honor roll a couple of times.

“When I first started at Leo, I took the bus. I had to jump right in, got a bus at 103rd and Halsted took it down to 79th Street. Back then it seemed like it was no big-deal. Going to Leo wasn’t like culture shock. I was used to integration. By the time I started Leo, the racial balance was 70/30 white, I’d say. By the time I graduated, it was probably the other way.”

If the first six decades of Leo’s existence promulgated, unfairly or not, a certain kind of social identity given its history and the neighborhood around the school, the rapid change meant Leo had to change. The school became a microcosm of larger developments. Transition was necessary, but not always easy, especially for those on the front lines.

“I felt a tension there at times. You’d see in more socially. In the lunchroom, blacks and whites were separated. Sports made it different, though and I wasn’t your typical student, either. By playing football, [black and white students] were in the same locker room, we practiced together, and we are trying to win games together. So we did all of that together.

“Al McGuire, the great basketball coach at Marquette, said something that will always stick with me. He said sports, especially in the sixties and seventies, have done more for integration than the Supreme Court could ever do. I believe that absolutely. A lot of the white football players at Leo then were probably not used to being around blacks. They were from Mount Greenwood, Bridgeport and the Southwest side and probably a lot of them weren’t used to being around black kids. Some of them probably had preconceived notions, maybe even some prejudice and some ignorance. By the time we were seniors, we were friends and got along great and that’s probably the beauty of it.

“Some of that was the Christian Brothers. Again, they had a reputation for discipline, everybody knew about [corporeal punishment]. In my case I didn’t see that. They upset me a lot. It was not racial. They were mean spirited to all people. Like I said, I went from [grammar school] nuns to the Brothers, so I didn’t have ay problems with them. If you talked to another African American who was enrolled at the same but was not a Leo man as far as sports, they might say something different.

It was not racial. They were mean spirited to all people. Like I said, I went from [grammar school] nuns to the Brothers, so I didn’t have ay problems with them. If you talked to another African American who was enrolled at the same but was not a Leo man as far as sports, they might say something different.

“I had some problems with some of my white students. There were times when I had to jump in and say, ‘That‘s not cool.’ I was an athlete, and that was different. The fact is if you’re scoring touchdowns, they were going to leave you alone. There was a group of us from St. Helena that started with me at Leo: Ken Mason, Dwayne Porter, Ronald Roscoe, though I’m not sure if he finished at Leo, Dwight Robinson. All of those guys went out for the football team.

“I had a ‘scholarship,’ though it was called grant-in aid. Tuition then was $750 a year, and we didn’t have a lot of money, so that was a big deal. I was blessed. I was very fast. It all started when we lived in Hyde Park.

“I was playing against guys that were older than me. My brother Norman, who went to Hales, was the first football player there to get a scholarship to a Big Ten school. He went to the University of Illinois. He started as a defensive tackle his sophomore year. In his junior year, he injured his knee against Purdue and he was never the same after that. Norman was six years older than me, and he used to bring me along to play with him. Because of my brother Norman at a very young age I was competing against older guys. As a result of that I matured faster than my peers athletically.”

Football was his outlet, and it provided a single direction and focus that impacted pretty much everything he did. “I wasn’t a profound thinker,” he said, but he absorbed everything and observed his surroundings. “Like most young kids, especially African Americans I was living a day at a time and all that I ever really thought about seriously were school and sports. Before I knew it I was a star at Leo. My freshman year we played nine games, and we probably went 6-3 or 5-4. We had a pretty good team. Put it this way, Bob Foster was looking forward to us becoming sophomores.

Football was his outlet, and it provided a single direction and focus that impacted pretty much everything he did. “I wasn’t a profound thinker,” he said, but he absorbed everything and observed his surroundings. “Like most young kids, especially African Americans I was living a day at a time and all that I ever really thought about seriously were school and sports. Before I knew it I was a star at Leo. My freshman year we played nine games, and we probably went 6-3 or 5-4. We had a pretty good team. Put it this way, Bob Foster was looking forward to us becoming sophomores.

“When I first came to Leo I was 5-feet, 5-inches tall, probably 145 pounds. I played running back, defensive back and I was a return specialist. During my sophomore year, I went both ways. I didn’t leave the field. I wasn’t that big, and the coaches, like Bob Foster, said that because it was such a long season, they made the decision to just keep me on offense. I had a natural flair, good speed and good vision and quick balance. I was practicing really well. There were games early in the year I didn’t leave the field. But the Catholic League was a very tough league.

“Looking back, when I was at Leo, the neighborhood was all black, but the school was majority white. Mount Carmel and De La Salle, it was kind of the same thing. People said that Leo would be the first to close, or that it would co-educational. All of these years later, and we’re still there.

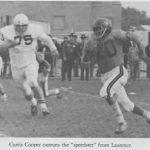

“Mount Carmel was our big rival historically, especially for the coaches. The same with Brother Rice and probably Rita. From my perspective it was different. Being from the Roseland area and going to St. Helena I had a lot of friends who played at Mendel. I had a lot of friends from the neighborhood that competed and went to school at Mendel. For me they were all rivals. In the Catholic League back then, everybody was your rival and everybody was really good. The only school we didn’t pay a lot of attention to, even though they were good, was Loyola, because they were so far away [in Wilmette]. The game was so physical and punishing and they’d really let you play. The hardest I was ever hit was during a game was Laurence.

“We used to scrimmage Gordon Tech even before our first game, because their coach [Tom Winiecki] was a Leo man and good friends with Bob Foster. I was kind of the marked man. They were always trying to stop me. I remember there was one play they wouldn’t let me go to the ground and they just kept hitting me. Probably the dirtiest team was Weber.

They were always trying to stop me. I remember there was one play they wouldn’t let me go to the ground and they just kept hitting me. Probably the dirtiest team was Weber.

“We practiced at Dan Ryan Woods after school and Gately was our home stadium. We played mostly Saturday nights or Sunday afternoon. The best game I ever had was against Mendel my junior year. I rushed for more than 200 yards. The best run I ever had was 92 yards. Bob Foster got so excited, he started running with me before his pants started to fall down. When we saw that during the film session, a lot of the guys cracked up.”

Personal style

Football was central, but a young Curtis showed resolve and quiet determination to gain his own independence. “I was in the middle of my family. During the summer starting my sophomore I worked at a Jewel store at 103rd and Indiana as a stock clerk. It was interesting. It gave me something to do and provided more discipline. Probably most important it allowed me to buy an inexpensive star. I was able to start driving to school, and that was pretty cool, to have that kind of freedom of movement.

“Bob Foster was one of my great influences at Leo. Bob was mean, but Bob was fair. If you produced, he was fine, but if you missed assignments or screwed up he was just mean. You couldn’t make mistakes with Bob. I got chewed out on the sidelines a lot with Bob. I was used to it after a while. I used to think: ‘Bring it on.’ If you produced, he didn’t care. Bob was all about winning. He taught history. Sometimes I’d get a message he’d want to see me. I‘d go into see him, thinking he was grading papers or going over his lecture and he‘d be there, sitting at his desk, drawing up football plays. That intensity and purpose I appreciate it now, I think. Looking back, I’d have to say Bob was pretty cool. [One thing for sure if you were a Leo man, Foster protected you.] He wouldn’t let anybody mess with you if you were on his team.

Sophomore Football

“I was a running back, and I also had spot duties on defense. If they had a wide receiver who was really fast or dangerous, they’d put me there to cover him. I also was back there for punt returns and kick off return. Probably nowadays that’s unheard of for one player to do all of that. That was something I could always hang my hat. The game back then was so physical. Football was pretty much a year-round sport. There was winter conditioning, weight lifting and spring practice. “Even before the season started to we went to St. Joseph’s [in Rensselaer, Indiana] for a special camp and preseason training. The way I remember is one year, we were there for probably a week. The next year I’d want to say it was even longer, probably ten days. We had triple sessions, so we practiced three times a day. It was grueling. I have to say, as tough as it was, when it was over, I felt strong. I felt could I could beat anybody. That’s the best shape I’ve ever been in my life.

“I was a running back, and I also had spot duties on defense. If they had a wide receiver who was really fast or dangerous, they’d put me there to cover him. I also was back there for punt returns and kick off return. Probably nowadays that’s unheard of for one player to do all of that. That was something I could always hang my hat. The game back then was so physical. Football was pretty much a year-round sport. There was winter conditioning, weight lifting and spring practice. “Even before the season started to we went to St. Joseph’s [in Rensselaer, Indiana] for a special camp and preseason training. The way I remember is one year, we were there for probably a week. The next year I’d want to say it was even longer, probably ten days. We had triple sessions, so we practiced three times a day. It was grueling. I have to say, as tough as it was, when it was over, I felt strong. I felt could I could beat anybody. That’s the best shape I’ve ever been in my life.

“I didn’t really do other organized sports. I practiced with the track team to help stay in shape and maintain my speed and endurance. I practiced with the flyweight [basketball team, the 5-8 and under team]. As far as sports, basically I just played football. During my junior year, I started getting letters from colleges and schools.

“Probably the highlight was when I got a letter from Notre Dame. It was signed at the bottom by Ara Parseghian. The letter itself was kind of vague. It wasn’t an offer. It just said, ‘We are interested.’ I was so excited. I showed it around the neighborhood. I was on cloud nine, just to get a letter from Notre Dame. Here I was, a young kid, from a tough neighborhood, trying my hardest to be avoiding gangs and staying out of trouble and now I’m getting letters from Notre Dame.

“I had offers from mid-level schools, like Northern Illinois and Western Michigan. St. Joseph’s wanted me badly. There was a guy named Mr. Kerns who was an assistant coach at St. Helena. He kind of adopted me as far as football. He was important in me going to Leo and he followed my career. He had a son a couple of years ahead of me who played at St. Joseph. I went down and visited.”

Family ties

His older brother Norman was such a dominant influence it made sense Curtis would gravitate toward a similar path. “I was familiar with [Illinois] and the campus because my brother was down there. I felt I could compete at a Big Ten school. I admit it was an ego thing. It was important to me. They also had a very good business department. Those were the factors that led me to go to Illinois, and I walked on.

“Back then, they called it grant in aid. I played down there, mostly on special teams. Mike Holmes was a year behind me at Leo. Mike first went to Colorado and then he came to Illinois. He was big time there. I wasn’t anything like Mike. I was labeled as a wide receiver. By the time I got to Illinois I was probably five-foot, seven inches and about one hundred and sixty pounds.

Illinois. He was big time there. I wasn’t anything like Mike. I was labeled as a wide receiver. By the time I got to Illinois I was probably five-foot, seven inches and about one hundred and sixty pounds.

“It was pretty eye opening, playing major college football. They recruited and brought in guys from everywhere. These were guys that were six-feet, two inches tall, weighed two-hundred pounds and could run the 40 [yard dash] in 4.5 seconds. They were bad boys, skilled, athletic and very fast. It was hard to compete against those guys. I stayed in shape. Most important I made some good connections and made a good life down there.”

Football was the means to pursue even greater distinction. He adjusted quickly to the privileged atmosphere. “I had a head for business. I liked business and I found it very exciting. I made the honor roll a couple of times down in Champaign. They had a subsidiary of Jewel’s down there Eisner’s Food Stores and I worked there over the summers.

New directions

“After I graduated I started handing out some resumes. One of the companies that caught my eye was Great America. At that time they were part of the Marriott chain. I got hired to work in their marketing department. I started out as a sales rep and eventually I became a regional manager. They were up in Gurnee. The way it works is you’re assigned territories. My territories were the South side, the south suburbs and Indiana.

“My job was to sell company outings, and deal with the human resources and personal department, employee benefits of different companies. I‘d go in there and said, ‘Take these tickets and make them available on consignment.’ [It was a way to provide incentives and benefits to their own employees.] I‘d also try to get corporations to have their picnics and other company outings and family events at Great America. Eventually I got promoted to regional manager. What that meant is that I trained other people to do the same job. It was fun, I liked it, but I basically outgrew the position. There was a ceiling at how much you could make.”

Mr. Cooper worked at Great America, now owned by Six Flags, from 1981 to 1988. He was ready for his next challenge. “I also had some friends who were working in radio,” Mr. Cooper said. Niche radio, especially programming tailored to the lucrative and rapidly mobile and expanding black middle class, exploded in Chicago and the rest of the country. It became a big and flourishing business. For the next two decades, Mr. Cooper made his mark for a number of radio stations in Chicago, most prominently V103, a legendary station noted for its rhythm and blues and classics programming. Radio became increasingly consolidated and a lot of conglomerates jumped in.

“I have one daughter, Courtney, who went to Marian Catholic in Chicago Heights. She‘s now at Illinois, so she’s second generation to go there. She‘s studying business with a minor in Spanish. She just finished doing a semester in Seville, Spain. When she was younger, we were in South Holland. Now, we live in Orland Park.”

An athlete by nature, Mr. Cooper was always interested in doing sports marketing. Four years ago, the perfect opportunity arrived. He jumped at the chance to work for the Chicago Bulls. He is now a senior account executive.

An athlete by nature, Mr. Cooper was always interested in doing sports marketing. Four years ago, the perfect opportunity arrived. He jumped at the chance to work for the Chicago Bulls. He is now a senior account executive.

“My responsibilities involve corporate partnerships, and includes everything from signage in the stands, to the rotating advertising you see at center court to radio advertisements during Bulls’ broadcasts. We do a lot of special promotions [special giveaways, player promotions] with companies like Walgreen’s or Harris Bank.”

Mr. Cooper works at an office suite at the United Center on West Madison. Because of the wide reaching ramifications of Michael Jordan and the dynasty he created during the nineties, when the Bulls won six championships in eight years, the Bulls’ brand remains an international one.

A new dream

Now, behind Derrick Rose, the Chicago high school legend, the Bulls are one of the league’s elite teams. They annual lead the NBA in attendance. “Winning helps of course. In radio advertising agency, you don’t typically deal with somebody from the company directly. It’s usually a middleman or somebody from the marketing department. With the Bulls, I [interact] with chief executive officers, top executives, the president of McDonald‘s, for instance, the big media buyers. I know guys that have juice and it‘s very exciting.

“That’s a key difference. When you’re selling radio advertising, you can close the deal by the end of the day. With the Bulls, you’re lucky if you can close a deal in a month. In radio, you’re dealing with fairly fixed amounts, low five-figures, maybe fifteen or twenty thousand at most. Here we’re talking about deals in the six figures that sometimes go up to $1.5 million, or multimillion accounts.

Leo made a lasting impression.

“I can’t really speak of it now. When I was there, the Catholic school shaped me with discipline. I understand now why mother insisted why we go there. The discipline and structure helped me, and it definitely kept us away from the gangs. On top of that it helped me get into sports and the fellowship and camaraderie that you get from being part of a team. From sports you not only had the added discipline, but you learned about goal setting. There were some growing pains. That football movie with [Denzel Washington], Remember the Titans, that was Leo to some extent. There wasn’t much mingling between black and white students. People develop and change over time. Now, I look forward to the alumni gathering every year.

“I enjoy talking with the [current] students. I’ve done some fund raising for them. Ben DeBerry called me once about me about helping raise money for the athletic department. We got together and recruited some other alumni, and we turned [the money] over to Leo. When they pick up and phone say they need, I jump in.”

I worked with Curtis at Marriotts Great America back in the mid 80’s. We were both Sales Managers. Curtis was a professional. Poised, strong business sense, nice guy, and had swag. We all enjoyed working with him very much! Great guy!

I want to say that Curtis Cooper was a great athlete and friend. My name is Gregory Lincoln and I was a Leo Grappler under John Byrne and team Captain and I got to meet Curt back then. Awesome Leo man and student and athlete.