Interviewed and Written by Patrick Mc Gavin 4/10

DONALD WHITESIDE ’87

The greatness of a man is measured from the neck up, Napoleon said. Donald Whiteside never commanded armies or fought in wars. He has from his early beginnings smart, shrewd and instinctive. He also was a guy that was never afraid to cut his own path. That instinctive feel for unselfishness and camaraderie has allowed for a varied and interesting life encompassing a background in athletics, academia, coaching and law enforcement.

and instinctive. He also was a guy that was never afraid to cut his own path. That instinctive feel for unselfishness and camaraderie has allowed for a varied and interesting life encompassing a background in athletics, academia, coaching and law enforcement.

He was young man who forged an identity of work, discipline, toughness and above all else, leadership. His innate skills in sports, particularly basketball, have paved the way for a remarkable life of travel, adventure and financial independence not typically associated with somebody who spent the first five years of his life in one of Chicago’s most notorious housing projects, the Robert Taylor Homes.

This man grew up largely left to his own devices, without the guidance of a male authority figure. He had his scrapes and acting out, but he also had a strong sense of decorum and right and wrong. Sports solidified him, gave his life meaning and value. It is just a part of his remarkable story.

It is one very much worth telling.

Origins

Young Donald was born April 25, 1969. “My roots started down in the Tennessee area around Nashville,” Donald says. “My grandmother was a very inspirational person in my life. She married a man with the last name of Martin, and she had two daughters. Then she remarried a guy, John Whiteside, my grandfather, the man whose name I took. My mother was their daughter. I think my mother got a lot of her traits from my grandmother.

“We started out in the Robert Taylor Homes and on my fifth birthday, we moved to Englewood area of 66th and Hamilton. My mother still owns that house. For grammar school I went to Luke O’Toole right around the corner, at 65th and Seeley. I went there for kindergarten and first grade. My mother was a single mother, and she decided to put my sister and me into a Catholic school. We started at St. Basil, on Garfield and Wood and we went there for the rest of our grammar school years.

“I was always in the neighborhood. I didn’t exactly detach myself from the neighborhood. I got into a little trouble when I was growing up. I’d carry a slingshot when I was growing up. I broke windows and threw rocks. Our house on 66th and Hamilton was a one-sided street. There were the railroad tracks on the other side, so I was always used to setting up cans and knocking cans off. When I started playing basketball, we made these homemade rims out of wood and we’d stand them in the middle of the street and we’d play full court in the middle of the street. After grammar school we’d started traveling more and playing in different parks against different people. Back then the neighborhood was a little safer. There were gangs back then, but they weren’t as bad as they are today.”

“I was always in the neighborhood. I didn’t exactly detach myself from the neighborhood. I got into a little trouble when I was growing up. I’d carry a slingshot when I was growing up. I broke windows and threw rocks. Our house on 66th and Hamilton was a one-sided street. There were the railroad tracks on the other side, so I was always used to setting up cans and knocking cans off. When I started playing basketball, we made these homemade rims out of wood and we’d stand them in the middle of the street and we’d play full court in the middle of the street. After grammar school we’d started traveling more and playing in different parks against different people. Back then the neighborhood was a little safer. There were gangs back then, but they weren’t as bad as they are today.”

He was a wisp of a kid, standing maybe five-foot tall and weighing maybe ninety-five pounds, dripping wet, as the popular saying went. He was quick, fast, alert to his surroundings and he had a direct, no-nonsense seriousness about the way he carried himself that people noticed. As the only boy in a family of four, including his mother, he was fairly solitary in his pursuits. He liked to read, and as he mentioned, play with that slingshot, but never in a malicious way. Interesting enough, the sport that would open up so many personal and career opportunities was a distant afterthought growing up.

Football and basketball were his first two loves. He loved the great Pittsburgh Steelers’ wide receiver Lynn Swann, a balletic and graceful player whose spectacular play in the Super Bowls made him an athlete many young kids wanted to emulate. As a south sider he also grooved on the exploits of Harold Baines, the great left-hand power hitter of the Sox.

“A bunch of the guys I used to play grammar school basketball with would say: ‘You need to come out for the basketball team.’ I’d tell them: ‘No. I’m not really interested in basketball. I don’t really like basketball.’ Eventually they convinced me to come out. This was the sixth grade. Actually I missed try outs by a day. They brought to the coach.

“He said, ‘Son, tryouts were yesterday. You’re a day late. These guys said you’re okay, so I’ll give you a look.’ They put us in a 2-3 zone and all I could do was play the top part of the zone and when they tried to pass the ball to the wing, I’d shoot the gap like a cornerback and steal the ball and dribble down fast and lay it up. That became the beginning of my basketball career. The coach gave me a ride home that night, and of course he asked me why I waited so long to come out for the team. That started a great relationship with my coach, and my two best friends from grammar school, John Hamilton and Corey Walden.”

He played baseball until the start of his freshman year of high school. He saw instantly basketball was his métier. This was the sport where all of his physical and mental attributes would best be put to use.

would best be put to use.

“Of course playing basketball grammar school, you go to a lot of tournaments. You go to a lot of leagues, and you play in the St. Sabina league, which is very popular. I got a lot of recognition playing in that. When it was time to go to high school, we all decided to go to De La Salle. The night before the test, my best friend called and he said he was taking the test at Leo.

“And I said, ‘Well, I am too.’ We both took the test at Leo. John was a basketball player up until high school and he was very good football player. Corey didn’t grow much once he got to high school and he had to make the transition from playing center in grammar school to playing guard in high school. He ended up being a very good football player, and he went to Purdue as a cornerback.

“[The Leo basketball coach] Jack Fitzgerald didn’t think I could play for him. You have to remember, I was a late bloomer physically and I was still very small. I started my freshman year at Leo, and I’d play a little open gym during recess and things like that. I impressed the guys a little. I had the bigger obstacle of convincing Fitz I could play. A prominent Leo guy, Mike Holmes said to me: ‘If you want to compete with bigger guys, you have to get stronger.’ I started doing putting push-ups and working out. That was motivation for me. I ended up going to trials, and I ended up doing well and impressing a lot of people and I ended up starting on the freshman A team. We went undefeated.”

The choice to attend Leo was fortuitous for both parties. Like a lot of young men, young Donald matriculated to Leo primarily out of solidarity and friendship with his two best friends. That was perhaps the original rationale, but things had a way of naturally going the route he had hoped.

“My two best friends were at Leo, and then all of the guys I played against at the St. Sabina league were there: Thor Palamore, Darryl Arnold, Asa Powell, everybody from that league went to Leo. We continued our development as basketball players there and just kind of jelled.”

When Donald started at Leo in the fall of 1983, Ronald Reagan was president, the country was finally coming out of a vicious recession and the neighborhood around the school was finishing its considerable social transformation. Demographically Leo was a racially mixed school, and basketball brought a lot of kids together, he said. To get to school he’d take the Damen bus to 79th and go east or the Marquette bus at Ashland down to 79th. His friend John Hamilton lived at 66th and Marshfield and two often planned their trips to rendezvous on their way to school.

When Donald started at Leo in the fall of 1983, Ronald Reagan was president, the country was finally coming out of a vicious recession and the neighborhood around the school was finishing its considerable social transformation. Demographically Leo was a racially mixed school, and basketball brought a lot of kids together, he said. To get to school he’d take the Damen bus to 79th and go east or the Marquette bus at Ashland down to 79th. His friend John Hamilton lived at 66th and Marshfield and two often planned their trips to rendezvous on their way to school.

“I tried a paper boy route and I tried working at Leo, painting lockers and doing stuff like that, but once I became a ballplayer, I was so dedicated to getting better, I just never had the time to work.

“I gained a lot respect very quickly, just being who I am. I’ve never been super outgoing and I’ve never been super shy. I was pretty good with people. I was not phony at all, so I made friends quickly. Leo’s always had its brotherhood. Once you became a Leo man, whether you transferred or not, you always remember that. Coming into Leo, we had guys like Marlon Maxie that went on. He ended up going to Julian and he had a good career, but we still had that connection. Asa Powell transferred to Phillips when things didn’t work out for him basketball wise, but we still have that connection. It’s like part of a fraternity, and once you’re in it, you’re there.

“When I got to Leo, the teachers were probably evenly split between the Brothers and the lay teachers. The Christian Brothers taught a lot of the classes, but there were other teachers that I had great relationships with. Coach Fitzgerald taught a class, either sociology or government class.

“Brother [Francis] Finch was an older Christian Brother who was fairly laid back. Brother Finch, they named the gymnasium after him. Guys would talk with him just to get the history of Leo. He taught chemistry. Brother [William P.] Doyle was one of my favorites. He was very spirited, very emotional and a Leo man of great heart. Brother Teasley was just different. He was African American. He wore thick glasses. Guys would try to make fun of him, but he wouldn’t go for it. He was very passionate about Leo. He didn’t go for any screwing around. I had a tremendous time at Leo. If I had to do anything over again, I’d never change that.”

Basketball

“I made the freshman team and we had some success. Coach Fitzgerald was still close mouthed about me. But if I had a good game, he’d tell me and give me encouragement. He kind of kept his distance. My sophomore year it was the same. The thing that [upset] him about me was we’d have summer league and I wouldn’t show up until about half the game was over because I was already playing so much around the house.

kept his distance. My sophomore year it was the same. The thing that [upset] him about me was we’d have summer league and I wouldn’t show up until about half the game was over because I was already playing so much around the house.

“It wasn’t that I didn’t want to play in the summer. My freshman and sophomore years, at Leo, I was playing a very structured game, and I felt like I was being held back whereas when I was playing regularly outside, with friends or different pick up games, I could do what I wanted. I also became more committed between my sophomore and junior year. Coach started to turn the team over to me. I was playing behind Randy Doss and Bob Anthony. Every year I had to keep trying out again. I didn’t mind. I wanted to show him how much I’d improved.

“He wanted me to step up and be a leader as a junior, and I probably didn’t step up as much as I could have because we had a great team. The only guys that played on varsity, as sophomores were Darryl Arnold and Damian Evans.”

At Leo, traditional was important, and a player’s progress tended almost ways to be hierarchal and based on merit, rather than reputation or promise. Players had to show they belonged and they were prepared to make the proper sacrifices. As a freshman young Donald quarterbacked a team that never lost a game. As a sophomore he showed considerable toughness that was not afraid to show an independent streak, if the situation called for it.

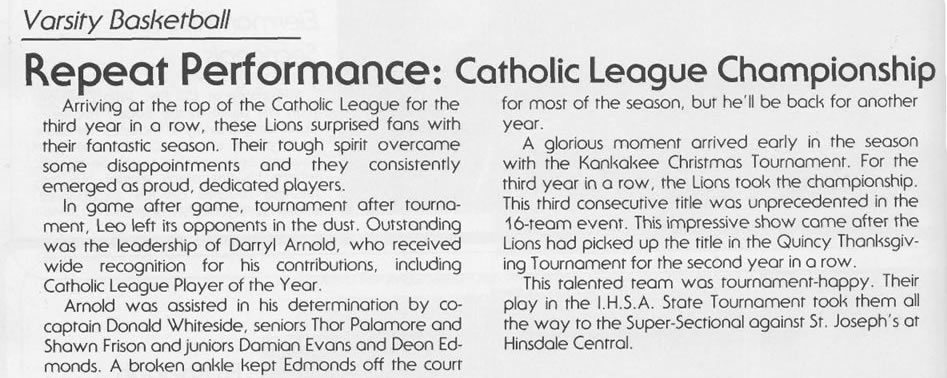

Fortunately for both, Donald and coach Fitzgerald worked out a détente. By the time of his junior year, Donald realized he was part of something very special. Coach Fitzgerald took over the Leo team after coach Tom O’Malley left to direct the program at Evergreen Park. Like the rest of the Catholic League, Leo joined the Illinois High School Association (IHSA). In Donald’s two years on the lower levels, the varsity Leo teams finished 42-12.

With Whiteside now part of a seasoned, talented group headed by Mr. Doss, Mr. Anthony and Chris Henderson, Leo proved to be in a class by themselves.

With Whiteside now part of a seasoned, talented group headed by Mr. Doss, Mr. Anthony and Chris Henderson, Leo proved to be in a class by themselves.

“As a junior I was more or less than sixth man. I’d come in and get some minutes, but I wasn’t really aggressive. When I was played junior varsity as a junior, I was really aggressive and [Fitzgerald] wanted me to carry that into the varsity games. I always felt the seniors had the spotlight and I didn’t want try to outshine them.”

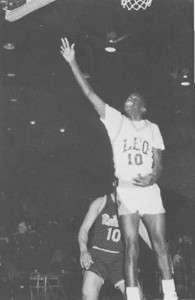

Leo captured the Catholic League and raced to out to a 27-2 record. The Lions were part of the large schools Class AA state competition. Leo won the regional and sectional title. They faced St. Joseph at the Class AA supersectional at Hinsdale Central high school.

The game was back and forth, featuring multiple lead changes and ties until St. Joseph wore down the Lions with their superior depth and pulled away for the victory.

After deferring to the team’s senior leaders, Donald knew it was now his time to take control of the team. “A lot of schools came in and saw us because we won a lot of games those two years on the varsity. They came into see as juniors because we had Randy Doss and Chris Henderson, who ended up going to Ohio State and DePaul. Bob Anthony went to a junior college and he ended up at Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Randy Doss ended up transferring there as well.

“I wasn’t super aggressive offensively, though I had the talent. There were a couple of plays that coach Fitzgerald ran for me. And when we ran them, I’d usually made a basket. It wasn’t like I couldn’t shoot. I knew where my talents were. I was a very good ball handler and floor general. We had guys that could score. We had Darryl Arnold, Thor Palamore, Damian Evans and guys coming off the bench like Deon Edmonds and Shawn Frison. We were pretty deep.

wasn’t like I couldn’t shoot. I knew where my talents were. I was a very good ball handler and floor general. We had guys that could score. We had Darryl Arnold, Thor Palamore, Damian Evans and guys coming off the bench like Deon Edmonds and Shawn Frison. We were pretty deep.

“In the Catholic League, our biggest rival was St. Francis de Sales. De La Salle was a good rival, but we never lost to them. St. Francis de Sales we lost to them in the regular season, but then we played them in the state tournament. My senior they were bigger than us. We lost to them at the Rosemont Horizon and that was the only team we lost to in the regular season. We were ranked No. 1 nationally for one or two days and then we lost to Simeon at the Rosemont Horizon.”

On St. Patrick’s Day of 1987, his senior year, Donald’s Leo team again faced St. Joseph in a Class AA supersectional at Hinsdale Central. The winner advanced to play in the state quarterfinals in Champaign. Donald registered 12 points, an assist and steal in what proved to be his final game for the Lions. The game was tied after three quarters, though again St. Joseph pulled away in the fourth. His career at Leo ended, but the range of accomplishment was quite stunning.

In Donald’s two years the team won 90 percent of their games, going 27-3 each year. The next stage in his life was deciding where to attend college.

“The first school to show interest that I knew about Loyola Marymount. We beat Dunbar on a last second shot for the championship of a Christmas tournament at Kankakee. The thing was, [Marymount] was on the West Coast and I wasn’t a big plane guy. I’d never flown in a plane and I wasn’t keen on flying in a plane.

“Northern [Illinois] was the only school that stayed in there. [The head coach] Jim Rosborough and his top assistant, Robert Collins, I’d talk to them on the phone. I’d gone on a retreat and sprained my ankle severely and I was wearing a soft cast. When I did my visit to Northern, I was on soft crutches. Jim Rosborough was very good about it. He came to my house, he talked to me and I believed in him. He was sincere, he told me about the other guys they’d signed and I knew most of them or played against them. I said I definitely want to play there. I was the last one to sign.

“Northern [Illinois] was the only school that stayed in there. [The head coach] Jim Rosborough and his top assistant, Robert Collins, I’d talk to them on the phone. I’d gone on a retreat and sprained my ankle severely and I was wearing a soft cast. When I did my visit to Northern, I was on soft crutches. Jim Rosborough was very good about it. He came to my house, he talked to me and I believed in him. He was sincere, he told me about the other guys they’d signed and I knew most of them or played against them. I said I definitely want to play there. I was the last one to sign.

“I loved it in DeKalb. Once I saw the student [athletic] center, a place where I could go play basketball and it didn’t close until almost Midnight, I was sold. Probably every school had that, but that I was the first one I’d seen. I just showed my ID and I could come in anytime I wanted. The biggest shock was being in school with women. Being at Leo with all guys for four years, I got to college and there were women wearing very loose t-shirts, everything was so laidback and I couldn’t concentrate at first. “

“Then when I almost lost the opportunity that’s when I really buckled down.”

In the first significant setback of his life, Donald was declared academically ineligible for his second semester at Northern Illinois. “The first orientation I came up to, I met with my advisor and I got all of these two hundred and three hundred level classes. Nobody really told me what that was. I just got my schedule and I went back home. My first year at school, I just got caught in a little bit over my head academically.”

He never lost his faith in his ability and he simply made the commitment to get his grades in order. “I padded my GPA that semester and it was never an issue after that,” he said. He could still practice with the team, but he was unable to travel with them for the road games. “The team would go on the road, but I couldn’t go. I could work out. I made friends quickly.

“I was friends not only with a lot of NIU students, but also the [Kishwaukee students, a local community college]. I would socialize a lot. The program wasn’t very popular. The biggest reason people wouldn’t go to the games is because they didn’t know any of the players. I’d say, ‘Now you know me.’ That would kind of increase our fan base. Some of the guys weren’t very social, so I had to patch that up and we started having success and turned the program around quickly.

Donald was part of an all-sophomore starting line up the following year. The program showed signs of improvement, but the administration made the then controversial decision to release Rosborough, after just his third year. The school replaced him with Jim Molinari, a member of the fabled DePaul coaching staff and a former player and protégé of the great Ray Meyer.

“Coach Molinari started focusing on the little things right away and he built a foundation. He started to turn things around. We started coming together a lot as juniors. In a 14-game home schedule, we won thirteen of those. The only one we lost was to Northern Iowa on a last-second shot. In all of our road games, we only won four, so we were 17-11. We had come together, and we learned how to win. We played a tough schedule.”

home schedule, we won thirteen of those. The only one we lost was to Northern Iowa on a last-second shot. In all of our road games, we only won four, so we were 17-11. We had come together, and we learned how to win. We played a tough schedule.”

It was a prelude to a magnificent and memorable senior year for Donald. “My senior year we started on the road against Maine. We won, and our next game was on the road against Minnesota. They jumped out on us 17-1 and it was a very good Minnesota team. We lost that game. Then we won eleven straight, with DePaul being the last time during that run. DePaul had really thrashed us the last game of our junior year.”

As the senior leader, Donald averaged nearly 12 points a game, led the team in steals and assists and played nearly 36 minutes a game for a Huskie team that won a school-record 25 wins against just six losses. NIU were the regular-season champions of the Mid-Continent Conference and earned an at-large berth in the NCAA championship against St. John’s at Dayton. “We started out and we had the jitters. We were down 25. We made a great comeback and I had a shot to tie the game with a minute to go. I just ran out of gas and I aired it. Even so, it was a great experience, great for NIU campus and the Midwest.”

At NIU, Donald lettered four years and he remains the school record holder for three-pointers made in a game (eight), season (78) and career (204). He is also number six on the school’s career-assists leaders and is one of only two players in school history to have recorded more than 1,000 career points and 300 assists.

Personal

“Originally I was going to go into accounting, but instead I went through general education and I ended up going into communication. I was interested in talking with people, so I went that route. It wasn’t really a hard decision. We got to write scripts and work with the cameras.”

The most profound moment in college also originated on a basketball court. It proved transformative in a wholly different way. “My second year at Northern, I was shooting in the athletics center, and a young woman came in with her roommate. Her roommate was very tall, about six-foot, three-inches.

“The roommate said can my friend have a shot, and I said, ‘Sure.’ She moved out of the way and here was this woman who was barely five-feet tall. They walked out of the gym and I thought that was the last of it. It was family week, and I figured she was somebody’s sister and she wasn’t even in college. It turns out some other people were trying to introduce her to my roommate.”

“The roommate said can my friend have a shot, and I said, ‘Sure.’ She moved out of the way and here was this woman who was barely five-feet tall. They walked out of the gym and I thought that was the last of it. It was family week, and I figured she was somebody’s sister and she wasn’t even in college. It turns out some other people were trying to introduce her to my roommate.”

Her name was Patrice Washington. Like Donald, she was a Catholic from the south side. They were a match. They have two children, Regina, a 15-year-old sophomore at Oswego East High and their son, Donald (DJ), an 11-year-old.

The next stage

“After my senior year, I told coach [Molinari] I didn’t think I was ready to play in [the NBA] and he wanted me to start coaching right then. I told him I still wanted to play a little more. Coach Rosborough contacted an agent and I went to Australia. I played in Hobart, Australia. I originally tried out with a Hobart team and a team farther up the Northeast coast. One team took Doug Overton and the other team took a guy who’d just been cut in the NBA.

“I went to a state league in western Australia about four hours from Perth. I didn’t have anything to do but play basketball. I was averaging like 41 points a game. They had me come over. I tried out for the team. We didn’t completely turn it around, but we had some success and became very competitive.

“The biggest guard’s name was Ricky Grace. I had really good games against him, and that propelled me into the spotlight. I went back the following year with the same team. It was a great experience. I didn’t make much money. Right after my second year, I went to South America and played in Venezuela for about two months. I had a good time down there. It was good money, I was paid in dollars and it was against better competition.

great experience. I didn’t make much money. Right after my second year, I went to South America and played in Venezuela for about two months. I had a good time down there. It was good money, I was paid in dollars and it was against better competition.

“I went to Latvia the following season. It was a good experience. There were some American players, a guy from Ohio State, another guy who played at Robeson, a couple of guys from the East coast. It was a hard league. It wasn’t a warm place, the conditions weren’t great, it was ‘old Russia,’ and I decided to come back and teach and coach basketball at Leo. It was the fall of 1995. I taught theology, history of religion, and I taught a couple of physical education classes.”

After a remarkable 17-year run of averaging more than 20 wins a year, coach Fitzgerald left to take the job at Richards High in Oak Lawn. Tony Rappold took over the Lions’ program. Coach Whiteside was a natural around the younger Leo kids, counseling them and giving them first-hand instructions on the proper way to play the game.

The coach still had an innate desire to play.

The biggest stage

“After my first year of teaching, my wife said, ‘You still want to play basketball, don’t you?’ I said, ‘Yeah, a little bit.’ She said, ‘Go ahead and I’ll support you.’ So I started working out really hard to get my name out there. I had a very good summer league, named MVP and played against some well known professional players. There were some agents who said they wanted to represent me and I said I wasn’t going to sign anything unless it was concrete and something on the table. A guy named Willie Scott approached me. He brought Larry Thomas, Isiah Thomas’ brother, to come and watch me play.

“I went back to teaching. I got a call one day. ‘This is Isiah Thomas.’ I said, ‘What’s going on.’ He said, ‘I’ve heard some good things about you and I was thinking about bringing you out here for a workout.’ He said, ‘How much do you get paid?’ I said, ‘I get, after taxes, about eight hundred dollars, every two weeks.’ He said, ‘When you get out here, I want you to act like I’m trying to give you two hundred and fifty thousand and they’re trying to take it away from you.’ I said, ‘Okay. I’ll see you next week.’

“Later I got a call saying they wanted me to fly out to Toronto. They bused us somewhere else in Ontario. All these guys were filling out these forms, about their medicals and everything. All of these guys looked and me and saw that I was nobody and just went back to what they were doing. I filled out my paperwork. The next day was the first day of workouts. We did a full court zigzag drill. I scored on a couple of people. It was just warm ups.

“It was a full court and two on two drills. I took the ball away, I dove on it and I got the ball and I kicked it out to Hubert Davis. He drove on Doug Christie, and he kicked it out to me and I hit a three. People started asking who I was. Later that night, we were doing drills where you’d play against different guys and if you made baskets, you’d play against rotating players until somebody stopped you. I kept the ball for ten possessions. It just blew up from there.

“I didn’t really know anything, when the training camp ended and the regular season began. I went back to my hotel room and I got a call from coach Fitzgerald. He said, ‘Congratulations.’ I said for what, and he said, ‘You don’t know’ and I said no. He said, ‘You made the team.’ I started getting all of this great attention from all over the place. I had a couple of big games to start the season. It was a fun ride. It didn’t hit me we were playing the Bulls. My idol [Michael Jordan] was at the other end. It’s really him and I’m really here.”

Coach Whiteside averaged about three points in 27 games with the Raptors. He remains, with 2000 graduate Andre Brown, as the only Leo alumni to ever play in an NBA game.

“I went to the [Continental Basketball Association] and played for the La Crosse Bobcats. I played for Flip Saunders. Even when I made the team in Toronto, a guy was writing me and said if things don’t work out they’d like me to come and play with them.

“I played in the CBA and then I went to Atlanta. The NBA is so different because everybody is trying to get to that level and it’s so selfish. I was just trying to be on a team trying to win. It was the same thing when I went to Atlanta. They had to take care of their investment. It was a nice ride. I got to tell kids about it, especially kids trying to get there.

“I left Atlanta and went to the Czech Republic. I went to a city, Opava about two or three hours from Prague. I loved every part of it, so much better than Latvia. I went to Prague every weekend. I had a ball, made good money. I got a signing bonus and I got another bonus for performance and how we did as a team. The only bad part was I got there too late to be eligible for the playoffs. Then I went to Spain. I had an out clause. My wife was pregnant. My daughter was already born by then and Patrice was pregnant with my son. She was miserable, and that made me miserable. I ended up leaving the team and coming home in playing in the CBA.

“After my son was born, I worked a regular job for a couple of years. I had an option of going back to the CBA or going to the [American Basketball Association].” He took part in on the inaugural Chicago Skyliners. They played their games at the Rosemont Horizon. Coach Whiteside played his final professional game in the summer of 2001 in the ABA championship at Kemper Arena in Kansas City.

The next challenge

Donald earned his degree in communication from Northern Illinois in 1994. He returned there as a top recruiter for coach Rob Judson, a former assistant coach at Illinois. It was his first college coaching job, and he relished the opportunity to coach in an excellent league, the Mid-American Conference and recruit the top conferences and schools in Chicago and the Midwest.

Coach Whiteside spent five years at Northern, enduring an up and down career. The administration decided to change coaching staffs. “When we were let go as coaches at NIU, I took a job as an assistant director at the NIU recreational center. I tried to keep my foot in basketball. He was looking for a job as an assistant.

He took a second job as an assistant coach at Kishwaukee, a community college near DeKalb. The program was pretty low. “I started making calls and recruited players from Chicago. I put them with some other guys and we took off from there.”

Interesting career move

“For the last three years, even though I was coaching [at Kishwaukee], I got to know the [NIU police] chief [Donald Grady]. We had some similar interests. We both like cars and we both liked movies. He said, ‘You need to come over here. I’ve got a position for you.’ He told me they wanted to take the aptitude test, which was held at the recreation center. I took both tests and I passed them. They wanted me to come over for these panel interviews, but I had a job interview to work the recreation center at Ohio State University. I thought I missed my chance. But they said they had a learner’s program where I don’t make the same amount of money as the other guys, but once I passed the tests, I would get paid like a regular officer.

“I went through the academy, a twelve-week course. I studied the law. It was fun.” Add to coach Whiteside’s multiple identities police officer. He has been a member of the NIU department of police and public safety for three years. He now balances that with his family, coaching and recruiting.

Donald Whiteside: student, player, coach, teacher, husband, father and police officer. Through it all, Leo provided the foundation. The school is always with him, he says.

“I think Leo was instrumental in character and development, my overall spirit, my outlook on life, I attribute to my time at Leo. That’s where I got focused on what I wanted to do, that’s where I set a lot of my goals.

“I was really happy with my time there.”

Wow, Mr. Whiteside! Wow! May God continue to keep you.