Interviewed and Written by Patrick Mc Gavin 8/10

EDWON SIMMONS ’93

What’s in a name, Shakespeare famously asked in Romeo and Juliet. Juliet observes, “That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” Names are sometimes a curse, but they sometimes get right at the heart of the matter.

but they sometimes get right at the heart of the matter.

Edwon Simmons is a good example. The name fits the personality, the drive and ambition he has demonstrated since he was an industrious and talented young boy determined to make his path. The slightly different spelling of the first name, contained in the “won,” bespeaks to something important and vital.

It has been his mantra, his mission, to win and achieve for himself and those around him. It’s not a win at all costs mentality, either, and taking pleasure in beating people so much as it means being connected to something meaningful and transcendent.

It also is, a little misleading, contained in the past tense. The preoccupation with goals and achievement remains, but now is tethered to a journey. His story has its own twists and turns, and says a lot about his attitude, passion and foundation.

“Everybody from my immediate family is from the south side,” he said, sitting down at a South Loop coffee shop to talk about his life and background. “Growing up, we lived at 59th and Carpenter before moving to 79th and East End. My mom, Claudette Patrick, raised me until I was about seven years old. Some things came up that she had to deal with, so she had my grandmother take care of me. My grand mother was named Elena Weatherspoon. She passed away six years ago.

“My [grandmother’s] mother came from the South, from Arkansas. My dad’s from Lakeland, Florida. He had five brothers, and two brothers played football, Ron Smith and Darnell Smith, in the NFL.

“I went from kindergarten to sixth grade at the local public school, and then my grandmother transferred me to Beasley Academic Center [at 52nd and State]. That was through the way of a recruiter named Dennis. He convinced my mom to send me to Beasley. Dennis was my baseball coach ever since I was ten years old. I played at South Shore, at Rainbow Beach. I played there, from the time I was ten to sixteen, when I played travel team.

“I went from kindergarten to sixth grade at the local public school, and then my grandmother transferred me to Beasley Academic Center [at 52nd and State]. That was through the way of a recruiter named Dennis. He convinced my mom to send me to Beasley. Dennis was my baseball coach ever since I was ten years old. I played at South Shore, at Rainbow Beach. I played there, from the time I was ten to sixteen, when I played travel team.

“Dennis was also at Leo. I graduated from Beasley in 1989, and there was really no other choice as far as where I was going to high school except Leo. There was no questioning it. My grandmother felt it was the best thing for me to do: go to an all boys’ school, have some structure and don’t have to worry about the girls and get my education and allow me to play sports, which was the backbone of my going to school.”

Baseball was Edwon’s first love. Family lore has him first playing the game when he was essentially just old enough to walk. “There was just something about it that probably goes back to when I was close to three years old and my great-grandfather used to put me on his knee and watch the Cubs’ games. One thing people always ask me is how do I live on the South Side and I’m a die-hard Cubs’ fan. I say, ‘That’s just how I was raised.’ I knew I was good in the game, with the speed, my arm, and my ability to hit the ball.

A new world

Young Edwon entered Leo in the fall of 1989. “It was sort of a clean transition. Beasley was one of the top elementary schools and it prepared me for high school. The difference was theology. That was something different for me, going to a Catholic school where we had to take theology. My family was not Catholic; we were Baptist. Learning the Catholic way, praying before class and learning the Hail Mary, things like were a little different. Once I got past that, the regular part of the school was a good transition for me.”

theology. That was something different for me, going to a Catholic school where we had to take theology. My family was not Catholic; we were Baptist. Learning the Catholic way, praying before class and learning the Hail Mary, things like were a little different. Once I got past that, the regular part of the school was a good transition for me.”

Yet, to some extent he was in this alone. “All of the other neighborhood kids were going elsewhere. I remember the day, August 21st, and I was on my way to school and they were still outside playing. The dress code was different: going to school and having to wear a tie and a collared shirt, when I was used to wearing jeans, a T-shirt and gym shoes. I went to Leo, and now it’s slacks, a clean long sleeve shirt, and tie and dress shoes.”

Baseball was not only his favorite sport; it became a conduit to Leo. “The good thing about playing baseball for Dennis is that a lot of the kids that were ahead of me were going to Leo, guys like Mike Anderson and Michael Moore. They talked about Leo. So, I knew about Leo talking to the baseball guys.

“Once I took the exam and walked around the school, I saw a lot of tradition. I saw the pictures on the wall of the older Leo men, the Leo alumni. You read about them and how they’re doing well and how they came in as a Leo boy and left as a Leo man. That was the thing I took from that. I took the keys to that and I wanted to be just like that, or even better.

“We lived two blocks east of Stony Island. It was a ride right down 79th Street. One of the good things was my grandmother was working on 59th and Western at the time. She would drop me off at school on her way to work. I caught a ride with her a lot.”

Sports were the gateway. The point of the team, a collective endeavor, was driven home. Baseball was his great love, but it was not the only thing. It opened up a world of possibilities. “My natural position was shortstop, and the good thing about coming to Leo, was I played on the varsity right away. I came in and started as a freshman and played all four years.

“Leo was also my first time ever playing equipment football. Our freshmen team went 8-1. We were compared to the team from two years earlier that went 9-0. We were undefeated and we played Mount Carmel in the final game. The game was tied, and we were driving and I threw a pass in the end zone, but our guy dropped it. We lost the game by six points. It was a heartbreaker. But we knew we had a great class, we had a great chemistry and we knew we had a great team. I played basketball as well. We won the Catholic League that year as freshmen. We went 27-0.”

“Leo was also my first time ever playing equipment football. Our freshmen team went 8-1. We were compared to the team from two years earlier that went 9-0. We were undefeated and we played Mount Carmel in the final game. The game was tied, and we were driving and I threw a pass in the end zone, but our guy dropped it. We lost the game by six points. It was a heartbreaker. But we knew we had a great class, we had a great chemistry and we knew we had a great team. I played basketball as well. We won the Catholic League that year as freshmen. We went 27-0.”

Camaraderie

Integration at Leo was perhaps slow in coming, but once it started, it ignited during the civil rights era. Edwon was part of a fascinating cultural era at the school, where the last generation of white students mingled freely and closely with the now predominantly African-American enrollment.

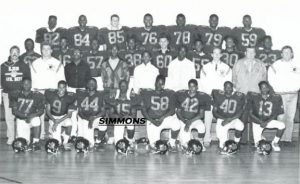

“We had Bryan Joyce, our tight end, and we had Frank Krugler, who was my guard. So we were probably the last class that had white guys on the team and those guys are like brothers to me. Even when we were freshmen, we just clicked. It wasn’t a white or black thing, it was just Leo men. That’s how we looked at it. That’s one thing I noticed about Leo: we never had racial animosity when we were there. To this day, I talk with Bryan.

“The Brothers were about discipline and structure, but it also seemed like they were adapting to what was going on at Leo. It was a transition, the whites weren’t coming as much, but the Brothers seemed to adapt to it, from Brother O’Keefe to Brother Doyle, to the point where we could come to them if we had problems in class or had a problem anywhere. Bob Foster was also a key part of that transition. He was my freshman coach, too.

“At home it was just my grandmother and I. That was a big difference for me being raised by women. I didn’t have a man in my life. A lot of the Brothers, the coaches, and a lot of the Leo teachers were some of my male role models as well.

“When I first entered Leo, I was probably five-feet, nine and probably a hundred and fifty pounds. By my senior year, I ended up being five-ten and a hundred and ninety pounds. I grew and gained some weight and definition. Once I got to playing organized football, I was a quarterback and already one of the leaders of the team. The team bonded together as freshmen that made me like football even more.

“Once I got to playing organized football, I was a quarterback and already one of the leaders of the team. The team bonded together as freshmen that made me like football even more. Going into my sophomore year, we were trying to win another championship. I broke my ankle the first game of the year and it was really a blow to the team. It was a blow to me, especially. It was a fumbled snap. I tried to pick it up, and an lineman dived and fell on my leg. That was the first year coach [Mike] Holmes coached me. After I was hurt, the team only won three games and it was a big disappointment going from 8-1 to 3-6. It basically had to do with me playing quarterback and being a leader.

more. Going into my sophomore year, we were trying to win another championship. I broke my ankle the first game of the year and it was really a blow to the team. It was a blow to me, especially. It was a fumbled snap. I tried to pick it up, and an lineman dived and fell on my leg. That was the first year coach [Mike] Holmes coached me. After I was hurt, the team only won three games and it was a big disappointment going from 8-1 to 3-6. It basically had to do with me playing quarterback and being a leader.

Life lessons

“I missed the whole season. I talked about coming back, but the doctor wouldn’t clear me. That’s one of the things I talked about, how we got along and grew, and that it didn’t really matter about color. Guys like Joyce and Frank Krugler, they’d come over to my house and talk to me about the game and say how much they missed me and just try to keep my head up. They’d come from Bridgeport, and that was a long ride for them. We’d sit and just talk. That was the bond of Leo. They weren’t really even thinking about white and black. That was a totally different side of town to them. They didn’t care. I didn’t care, either. Sometimes I’d go over to Bridgeport and go over to Krugler’s house and his mother would make sandwiches. We were brothers.

“I was healthy enough to play basketball, and we won the sophomore championship as well. I was healthy enough to play baseball. That was probably our best year.

By the time I was a junior, I started to get pretty seriously recruited by different schools. Miami, Northwestern, Houston, Illinois and Florida International call came to watch me play. Baseball was a no-brainer for me. One thing I was focused on about was getting drafted. I didn’t know which one I wanted to do. I wanted to lead Leo to the Catholic championship in football.

By the fall of 1992, Edwon was a team leader. He was the starting quarterback, the pulse of the team. The team played off his spark and energy. “We played St. Rita at Gately [my senior year]. The game was played on a Sunday, so we were the only [high school] game. Rita started out ahead of us 14-0. Richard Willock had five touchdowns that game. The game went to overtime.

“It was third down. We were on about the seven-yard line. We called an option. Instead of pitching the ball, I kept it and took the ball in and scored. It was like something driving me inside, almost saying, ‘You can’t be tackled, or you can’t be stopped.’ Once I turned the corner, it just felt like I had some kind of extra energy that told me I would get into the end zone. It was just a desire to score. The fans on our side went crazy. Rita was our big rivalry. For our class, that was probably one of the best times of my high school career. We’re the last class that ever beat St. Rita in football.

“What was crazy about that [Rita] game was that it seemed immediately after all of my football [recruiting] letters just started coming in. I got a letter from Illinois, Eastern Illinois; it was amazing because I didn’t think anybody really looked at me as a football prospect because I was an option quarterback and not really an efficient passer, like a Donovan McNabb.

“I was a leader and I was a winner. The coach Randy Johnson described me as the heart and soul of the team. I ran the option as best I could. I wanted to get everybody involved in the offense and get the ball to our running back Richard Willock, who was definitely our go-to guy. That team bonded. We started 6-0. We lost to Loyola. We qualified for the state playoffs in the 5A. We won our first game in the state playoffs against Robeson. We came back and had to play Simeon, and they beat us at Gately.”

He stopped playing organized basketball after his sophomore year. He was a scrappy defensive specialist who typically was assigned the other team’s best offensive player. “It was coach [Jack] Fitzgerald’s last year, and I always tell this story about Fitz. He said, ‘Simmons, I have a uniform for you, but to be honest you’re not going to play, so it’s up to you what you’re going to do.’ I thanked him for his honesty, so I decided to get a job and just get ready for baseball.

“That’s what I always liked about Leo and the coaches there: they were always honest with you. They always told you straight up, ‘I think you can play. I think you’re not going to play.’ Straight to the point. That’s what you want. I worked basically after my sophomore year, I worked at Champ Sports, at Evergreen Plaza, during basketball season only. During my junior and senior year, I always worked during the basketball season just to have a little bit of extra money in my pocket.”

A different professional

“By this time I was torn between the next step in my life. The ACT tripped me up as well. I had a 16.5, and I needed a 17. I had one final time to take the test, but it just so happened to come the day after our senior prom. After a night of prom, I just couldn’t get up and missed the test.

“By this time I was torn between the next step in my life. The ACT tripped me up as well. I had a 16.5, and I needed a 17. I had one final time to take the test, but it just so happened to come the day after our senior prom. After a night of prom, I just couldn’t get up and missed the test.

“I decided to just go for the [amateur] baseball draft. I got drafted in the ninth round by Baltimore. I played rookie baseball in Sarasota, Florida, came back the following year for a higher level of rookie ball and then I played Class A in Frederick, Maryland. They drafted me as a shortstop but converted me to play third base.

The experience was very [humbling] because I thought I knew the game, but I didn’t really. I was going basically off God-given talent. The coaches at Leo knew the game, but once you get down [to the professional organization] it is a totally different aspect of learning. They teach how to correctly field a ground ball, how to correctly bunt, how to correctly understand the sacrifice and how to correctly run the bases. Culturally, it was different, playing with mostly Latin ballplayers.

“The schedule of baseball was tough for me. It was kind of punishing. We’d get up early, in the morning from eight to eleven, in the hot sun, have lunch and then be back on the field for a game. The game was either at our local stadium, or we’d have to travel by bus, the longest we’d ever travel was usually about two hours. That was just a whole lot of baseball for somebody who was just 17 years old.

“It was the first time I was really by myself, being alone. I want to say on my first team, we had maybe three Americans, and even some of them were [higher level players] doing rehab so I didn’t even really get a chance to speak with them. Most of the guys on my team were Latin, and they only spoke Spanish, so there wasn’t a lot of communication.

“Playing minor league ball taught me how to be a man really fast. There are things you have to do: get there to practice, be on time. They’d put us in hotels, but we had to pay our rent. Looking back on it I think I should have just went to college. To this day, every young man who wants to play baseball, I tell them there’s no reason to rush and play minor league baseball, when you can really play minor league in college and get your education at the same time. Once you finish your chances of getting into Double A is much higher out of college than high school.

“There were other high school players who were brought down, but where you were drafted had a lot to do with the investment these professional teams put in you. How much money they invested in you determined how much time they put in you to develop and become a better baseball player. Some of the high school guys were drafted later than me, but they only lasted a month or so and then they were cut.”

Jordan rules

“One interesting thing that happened was that the year I spent in Class A was the same year Michael Jordan was in spring training with the White Sox. When we were in Sarasota, we always played the White Sox. That spring Michael was down there, we played them once a week and it was just crazy. It was always exciting to see him down there. I used to joke with him when he’d be in third base, I’d say: Michael, I’m from Chicago. It was always a conversation like that.

“Leo was one of the things that prepared me for [the minor leagues] because I was used to dealing with different people, black and white, I had that interaction high school, and I think it would have been more difficult had I not had that experience. Playing minor league, I had some injuries. I broke my finger and I also broke my nose. They gave me my release papers. I was upset, of course, but I came back to Chicago, in 1997.

it would have been more difficult had I not had that experience. Playing minor league, I had some injuries. I broke my finger and I also broke my nose. They gave me my release papers. I was upset, of course, but I came back to Chicago, in 1997.

“I decided I wanted to try and play football. I asked coach Holmes whether he still had his connections at Illinois. Because I did not qualify [academically], Illinois wanted me to go to junior college and Parkland was right there [in Champaign]. I went down to Parkland and I got my associate’s degree. That spring, [coach Lou] Tepper was fired and I was without the chance to go to Illinois. The new coach, Ron Turner, was not going to honor the scholarship.

“A couple of years earlier, when I was finishing Leo, I re-bonded with my father. One of my uncles on my dad’s side was Ron Smith, a receiver who played with the Philadelphia Eagles. He went to San Diego State. I talked with my uncle about playing in college. He said he could make a call to Ted Tollner, who was the coach there. I still had tape from Leo, which I sent out to them, and my uncle also let them I know I played minor league baseball. One thing my grandma made certain when I signed my [baseball] contract was that they provided for my schooling in there. Major league baseball, or I mean the Orioles, had to pay for my schooling.

“Once they saw the tape, they had me come down. I was basically a walk on, because I didn’t have to pay [for my tuition] or cost them a scholarship. I met them, it was a good fit. San Diego was a beautiful place, the school was beautiful and they allowed me to join the team. I had a good time. We’re the last class to go to a bowl game. I played with Az-Zahir Hakim and Kyle Turley, guys that played NFL. I played safety and mostly special teams.

“It was quite an experience. We played at Jack Murphy Stadium. The first couple of weeks, the Padres were still playing, so you’d have the dirt and infield on the field. It was exciting also because you were playing in an NFL stadium as well. You could see the alumni, the student body, it was a totally different atmosphere when you play major college football. We called our uniforms ‘tuxedos,’ because they were all black. We were in the old [Western Athletic Conference], so we played BYU, Boise [State] and Utah. We played North Carolina in the Las Vegas Bowl. We lost the game, but it was very interesting.”

New challenges

Mr. Simmons graduated with his degree in psychology from San Diego State in 1999. His journey was an interesting, even unorthodox one, and he had a point of view and subjectivity that was different than most. He was forced to adapt quickly to the outside world, and learn how to get by on his own.

Mr. Simmons graduated with his degree in psychology from San Diego State in 1999. His journey was an interesting, even unorthodox one, and he had a point of view and subjectivity that was different than most. He was forced to adapt quickly to the outside world, and learn how to get by on his own.

“I went to Iowa City where my Leo classmate, Richard Willock, played football. He tried the pros, and it didn’t work out. Some teammates from Iowa invested in a clothing store. I helped Richard run this urban clothing store. We sold clothing and shoes. We did it for three, almost four years but then the recession hit. I moved back to Chicago, and I became a counselor and I worked for a social service agency for a couple of years.”

He was reconnecting with his mother and just as significantly, his younger brother Jason Avant. “We lived together for a short time, when he was just a baby, probably about nine months. That’s when I went to live with my grandmother and he went to live with his father. We were separated. He was going back and forth between Chicago and Decatur. He was about nine years old and he came into Champ Sports, where I was working. I told the manager he didn’t really have the right pair of shoes and pants. He gave me an advance on my check, and we got him the right kind of shoes and pants. We were connected for a while. Then he moved back to Decatur.”

Their journeys separated them. With Mr. Simmons involved in his career in Iowa City and then working in Chicago, he lost contact with his younger brother. What he did not know was that his brother was a brilliant athlete in his own right who became the top-rated football prospect in Chicago as a wide receiver at Carver High. Jason was also a coveted basketball recruit. Football was his game.

Fortunately for Mr. Simmons, he had a fortuitous encounter with a cousin of his younger brother. “I ran into him at a lounge, and I asked him, ‘Where’s my little brother?’ He gave me a number to reach him. It was probably one o’clock in the morning when I called him. He was in his freshman year at Michigan. I said, ‘Bro, where are you?’ He said, ‘I’m at the University of Michigan playing football.’ The following weekend I went down and watched him play at Michigan. Once I went to Michigan, it’s been nonstop. After that, I never missed a game at Michigan. Now, we’re like two peas in a pod.”

Jason Avant was a college All-American at Michigan. The Philadelphia Eagles drafted him in the fourth round of the 2006 draft.

“Once Jason got into his junior year at Michigan, I started collecting phone calls and helping him decide what [sports] agency he was going to sign with. Whatever agency he was going to sign with, I was going to do scouting for the following class. He ended up signing with Octagon. I worked with them as a talent scout who helped them sign guys that followed Jason at Michigan. I helped them sign Leon Hall, Lamar Woodley and Charles Godfrey.

“I’m still working with Octagon, consulting with them. My brother is going into his fifth year, and one thing we started was a foundation. This past year we did his first football camp, as part of his foundation at Morgan Park. We had ninety-eight kids, and I was happy about that.”

Mr. Simmons’ own work and career were two-fold: he worked with the sports agency recruiting new clients. He worked in social services, primarily for at-risk kids who were struggling academically.

“I do tutoring for Silver Learning Center. Last year I was at T.F. North [in Calumet City]. We tutored kids during the lunch period; it was the pilot program and it went very well. We focused on kids that were struggling, and we helped them. We came in the third quarter and any kid that was failing two or more classes in their third quarter passed in the fourth quarter. I’m excited about that, and ecstatic about education and helping the kids that lack motivation or don’t want to go work. I tell them: we’re in school. We might as well get the work done. We want kids to have options.”

He also has his own family. Mr. Simmons has three children, daughters Arion and Alexandria and his one-year old son, Tyler.

Coming home

At the invitation of coach Holmes, Mr. Simmons added a new title: coach. He is working with the Lions’ varsity who works with the quarterbacks and wide receivers. It satisfied something deep and elemental, coach Simmons said. “I decided I had to come back to Leo. I want to instill the tradition of hard work and never give up attitude. I’m excited. The kids are totally different when I was coming up. It seems like we had more desire to always want to win. We wanted to go to practice. We wanted to get better. I’m trying to teach them about the need to be on time and being prepared.

“We have a talented quarterback [Gerard Baker]. I want to guide him and show him to be a leader. We’re trying to show how to play for one another, how to be leaders, not about talking, but going about your work and leading by example and everything else will fall in line. I’m constantly getting on the seniors that they’ve been here for four years, and also let them know this is their last year. The majority of kids don’t play football after high school.”

By going backward coach Simmons moves inexorably forward.

“My heart is with Leo, and it will always be with Leo. Until I die, I’ll be a Leo man.

It totally gets you to be disciplined. It’s all about discipline. You know what you have to do. Your schedule is laid out for you. You’re expected to do this, and if not, there are consequences to that. You didn’t want to have to deal with the consequences. You learn so much in those four years of high school, and it elevates you to college and after that.

“That’s one of the things we’re trying to do with the black alumni is we’re trying to get more black alumni to come back and explain to the kids we have now at Leo that you can be whatever you want to be if you just keep your heart and mind and stay on the structure that Leo gives you. It gives you the perfect structure of how to be a real man. We need men to raise men and men to be men.

“Mentoring and coaching is so exciting. I have pride wearing my orange all the time. Yes, I am a Leo alumnus. We have pride in this school, we have pride in you. It’s not just a school. It’s a brotherhood. Some guys go away to school and they join a fraternity. That’s their second fraternity.

“Leo is the first fraternity.”

Speak Your Mind