Interviewed and Written by Patrick Mc Gavin 3/10

Interviewed and Written by Patrick Mc Gavin 3/10

JAMES J ARNEBERG ’45

Scene: The Southwest Side of Chicago.

Time: The mid-1930s, the height of the Great Depression.

It was a volatile time when people moved and acted with a naked desperation, regardless of their age, to get by, to feel worthy and to achieve self-respect. The city’s south side was exceptionally sectarian; it wasn’t just what parish you belonged to or public school you attended. You were always identified with a group, a gang. Associations, friendships, and clans, were quite popular.

A group of young kids in the Little Flower parish proclaimed themselves “The Honore Gang,” named after the street positioned between Wood and Wolcott and caught between the major thoroughfares of Ashland and Damen. Perhaps the group’s reputation exceeded their actual mischief, but most kids of a comparable age who weren’t a part of the group knew to avoid them. People, after all, especially kids, had to get where they were going. Sometimes, however, running into them was unavoidable.

A young boy named Roger Coughlin, probably no more than eleven or twelve years old at the time, was trying to get to 82nd Street from 81st Street on Honore. In the midst of this very quotidian, unremarkable act, young Roger, a resourceful young kid (he would later become a well-known priest), found his pulse quickening and nerves on edge when he spied a couple of the notorious gang cutting across the street to intercept him.

A young boy named Roger Coughlin, probably no more than eleven or twelve years old at the time, was trying to get to 82nd Street from 81st Street on Honore. In the midst of this very quotidian, unremarkable act, young Roger, a resourceful young kid (he would later become a well-known priest), found his pulse quickening and nerves on edge when he spied a couple of the notorious gang cutting across the street to intercept him.

He steeled himself for a confrontation. “I was sure I was going to take my lumps,” he said, recalling the afternoon to a friend years later.

At the moment when the two forces were about to collide, young Roger saw another figure approaching from the opposite direction. “Jimmy Arneberg came walking down the street. He saw me and said, ‘Roger, how are you?’ Those Honore guys just turned around and went running the other way.

I knew Jimmy saved the day for me.”

What is noteworthy, is that Jimmy Arneberg, at the time, was not an adult; neither was he a young man. He was a boy, the same age as Fr. Coughlin. Even at a young and precocious age, James (Jim) J. Arneberg, acquired a remarkable mystique about himself that clearly set him apart from his peers and friends.

“He had a presence,” said Mark Dwyer, a 1966 Leo graduate. “You always knew when he was in the room.” He had constantly shifting and overlapping identities from birth to death: Student, player, soldier, scholar, coach, teacher, administrator and husband and father.

He was a warrior and poet in the best sense. He had the sometimes contradictory aspects of character and psychological profile that resisted easy interpretation. He was an athlete and intellectual. He was fearless, indomitable and aggressive though sometimes shy and emotionally circumspect. He was demanding and unflinching, though he also had a remarkable ability to find and shape talent, even in those who didn’t know they possessed it.

He was of his time but also somebody who clearly transcended it, say those who knew him best. Today, nearly twenty-five years after his death, coach Arneberg casts a long shadow and has had a permanent impact over those who knew him.

“I think of my dad every day and I think of Jim,” said Jim DeLisa, a close friend who was recruited by and played football for coach Arneberg at Saint Joseph College in Rensselaer,  Indiana.

Indiana.

He had, it is safe to say, a golden touch. For a man who died tragically from complications of colon cancer at the relatively young age of 59, his level of accomplishment was staggering. In football, his name was synonymous with victory. In his three years at Leo, his teams lost only one game; they twice won the city’s most prestigious game, the Prep Bowl, played at Soldier Field, pitting Chicago’s best Catholic and public school teams. He is almost certainly the only man to have won the game as both a player and a coach.

As a Marine, he fought valiantly in some of the fiercest battles in the Pacific theater. He saved the life of one of his closest friends. He never boasted about his time and experience there; indeed he tended to downplay his own bravery. He saw his military service as an act of duty, sacrifice and national service.

He had a dark, even morbid, sense of humor about his military service at times. He joked with friends, sometimes showing the scars of the bullet wounds on his chest and observing that if the Japanese were better shots, he’d have spent Easter with the Good Lord. He saw firsthand what his later work as a scholar and historian confirmed, that war was filled with suffering, hardship and death. The exploits and repercussions were not to be used for personal gain or self-aggrandizement.

The stories about him are legendary, to the point that many appear too apocryphal to be true, such as the one in which he was struck by a bus and refused medical treatment because it would interfere with the basketball game he was scheduled to coach. This article is not intended to disentangle fact from myth. It is rather the celebration of a remarkable life, one very much worth revisiting.

Origins

Under his 1943 senior photograph in the Leo yearbook, Jimmy’s list of achievements had a spare simplicity:

James J. Arneberg

Class officer 1,2,3

Lightweight football 1

Heavyweight football 2,3,4

Bantamweight basketball 1

Lightweight basketball 2,3,4

Intramural champs 2,3

James J. Arneberg was born in 1925 (not coincidentally, the same year the Irish Christian Brothers opened Leo). His father, Louis Arneberg, worked in the can company business. His three older brothers were all excellent athletes and students at Leo. The oldest brother was John, followed by Bob and Billy. Jimmy had a sister, but she was tragically killed at the age of four after a Chicago streetcar struck her. Jimmy and his two closest friends, Tony Kelly and Bob Kelly (no relation), were precocious football stars at Cook, the public grammar school they all attended.

In the fall of 1939, just days after Hitler’s armies crossed into Poland, Jimmy and his friends started their high school career at Leo. Richard (Dick) Pendergrast also entered Leo in 1938. “He was going to Cook, and I was going to Little Flower, but I knew him because we lived at 80th and Marshfield and Jimmy lived at 82nd and Marshfield.” Mr. Pendergrast noted.

“John Arneberg, the oldest brother, was an aggressive guy and he was a really good football player at Leo. The second brother was Bob, and he was a good football player, too. As a kid, Jimmy was an extremely pleasant guy. Everybody liked him, and he was very physical and kept himself in great shape,” Mr. Pendergrast said.

Jimmy was an extremely pleasant guy. Everybody liked him, and he was very physical and kept himself in great shape,” Mr. Pendergrast said.

Arneberg was a three-year starter on Leo teams that are arguably the greatest in the school’s illustrious history. They won an unprecedented three consecutive Catholic League conference and city titles. During those three years, the Lions posted a record of 30-1-1, which included undefeated back-to-back Prep Bowl championship teams which won 22 straight games in the 1940 and 1941 football season. The coach, A.L. (Whitey) Cronin, had a career winning percentage of .806 (91-17-3) in his 13 years at the school.

During Jimmy’s sophomore year the team had a ferocious defense that was scored upon only once. Leo beat DePaul 7-6 in the Catholic championship game.

The first school photograph of Jimmy shows him wearing uniform number 77, the fourth from the left in the top row. He displays a ferocious smile and appears as very friendly and approachable. In Jimmy’s junior year, Leo was a juggernaut; they were a feared and lethal team that historians say was probably the greatest high school team in the country that year. The interior line of Jimmy, James Gallagher, Larry Forst, Chuck Mehmel and Frank Lauro was quick, athletic and overpowering. They created massive holes for star running backs Bob Hanlon, Bob Kelly and quarterback Babe Baranowski.

In 1941, Leo was matched against Public League power Tilden at Soldier Field. In front of a crowd of more than 95,000 people, the Lions decimated Tilden in racing to a 39-6 lead at halftime. It was the most lopsided final, 46-13, in the history of the game to that date.

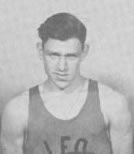

Jimmy was not, even during that era of physically smaller players, an exceptionally big guy. A photograph from the 1943 yearbook shows him in football stance. It is a staged photo and it shows him without his helmet. He looks up at the camera, and makes a stunning impression. His back has a perfect V-shape symmetry, and his legs and calves appear to be incredibly powerful. He was a technician, he was very disciplined, but also industrious and intuitive, and someone who always knew how to thwart his opponent.

Jimmy was not, even during that era of physically smaller players, an exceptionally big guy. A photograph from the 1943 yearbook shows him in football stance. It is a staged photo and it shows him without his helmet. He looks up at the camera, and makes a stunning impression. His back has a perfect V-shape symmetry, and his legs and calves appear to be incredibly powerful. He was a technician, he was very disciplined, but also industrious and intuitive, and someone who always knew how to thwart his opponent.

He was the perfect player at the right time and place. Bob Zahren was a South sider who played with Jimmy at Loras College after the war. He was a year younger than Jimmy, and knew of him since high school when Bob was a rival player at Mount Carmel. “My junior year was the best team I ever played on and we lost [to Leo] 6-0. We finally beat Leo my senior year, but we weren’t nearly as good that year as the year before. That Leo team was just too good.”

The 1942 Leo team recorded four shutouts. It opened the year with a 39-6 demolishing of Loyola, the jumpstart to another remarkable year. In the Lions 46-7 whacking of St. Patrick, Jimmy started the onslaught when he blocked a punt and returned it 20 yards for a touchdown. More than 35,000 fans had gathered for the annual “Mercy Charity,” game at Comiskey Park. Leo showed their fierce rival, St. Rita, no mercy, as they whipped the Mustangs 26-7.

The game of the year was against the school’s historic rival, Mount Carmel. More than 10,000 people jammed the stands at Shrewbridge (now Stagg) Stadium at 74th and Morgan. The Caravan recovered a fumble early in the game and appeared on the verge of scoring. The Lions mounted a great goal line stand and stopped the Caravan inside the five-yard line. Leo’s Don Murphy passed five-yards to Bob Baggott for the game’s lone touchdown. A week later, Leo destroyed Fenwick 33-13 in the Catholic League championship game.

Caravan recovered a fumble early in the game and appeared on the verge of scoring. The Lions mounted a great goal line stand and stopped the Caravan inside the five-yard line. Leo’s Don Murphy passed five-yards to Bob Baggott for the game’s lone touchdown. A week later, Leo destroyed Fenwick 33-13 in the Catholic League championship game.

Six players from that Leo team earned all-area, all-conference or all-state recognition: Jimmy Arneberg, end; Bob Hanlon, fullback; Bob Walsh, end; Tony Kelly, center; Bob Baggott, end; and Bob Kelly, half back. Bob Kelly also won the Noble E. Kizer trophy for the most valuable player in the public and Catholic League.

Two years earlier, in the yearbook, Jimmy’s expression was open, curious and suggestive. Now, his face, with its intense, deep set eyes, closely cropped hair and stocky, solid and wide build, projected seriousness intensity and concentration. His look probably reflected the mood and pessimism of the moment. Hitler’s armies had devastated much of Europe and North Africa; the Third Reich had achieved the high point of its military power, territorial expansionism and foreign occupation. The situation in the Pacific was also quite grave, with the Japanese securing stunning military victories against Allied forces.

The games served as a necessary diversion from the bleakness of what was happening in the rest of the world. Jimmy and many of his classmates did not shirk what they regarded as their moral obligation to defeat fascism and preserve American democracy. “There were twenty of us from the Leo class of ’43 that went into the Marines,” Mr. Pendergrast said. “We graduated in June 1943 and we were all pointing towards military service at the time. I left Chicago July 9.

“They would start a platoon every time a new group of recruits came in. Jimmy was about two weeks ahead of me in boot camp. We went to San Diego. When I got out of boot camp, I tied up with a classmate from Leo named Ed Power who played football with Jimmy. In December 1942, our senior year, Ed and I worked for the Railway Express downtown during the Christmas holidays. We worked with a fellow by the name of Izzie Kagan. Ed and I became friends with Izzie, who was from the West Side.

“Eddie got out of boot camp at Great Lakes and he was sent to San Diego to be on one of the destroyers. He and I got together for liberty. There was really only one place to go if you were a Marine or sailor, and that was up and down Broadway, which was kind of the main drag. We were right in front of the YMCA Building. That’s where people used to congregate. We were on the south side of the street and I heard somebody shouting, ‘Dick, Dick,’ and I looked across the street and it was Jimmy Arneberg.

“Eddie got out of boot camp at Great Lakes and he was sent to San Diego to be on one of the destroyers. He and I got together for liberty. There was really only one place to go if you were a Marine or sailor, and that was up and down Broadway, which was kind of the main drag. We were right in front of the YMCA Building. That’s where people used to congregate. We were on the south side of the street and I heard somebody shouting, ‘Dick, Dick,’ and I looked across the street and it was Jimmy Arneberg.

“Jimmy ran right through the traffic, cars honking, cut through traffic and his buddy was coming behind him. Jimmy was always an outgoing guy, and he wrapped us both up in a bear hug. He said ‘I want you to meet my buddy, Izzie Kagan.’ Of course, Ed and I already knew Izzie from working with him. Jimmy and Izzie went into the same outfit, the 4th Marines. Everybody else went into different directions. I was a telephone man and I went to communications school in New Caledonia and then down to Guadalcanal.”

Their paths diverged, though it did not take long for stories of Jimmy’s exploits to come back to Mr. Pendergrast. “After the fighting was over in Guadalcanal, it was a training area and I was there with the replacements. I used to be able to go down to the 4th Marines and visit Jimmy and Izzie and some other guys down there from Mount Carmel who were friends of Jimmy’s. When the training period began, everybody would go back to the barracks.

“Jimmy would stay out there and run the course on his own. That was his personality. He always wanted to do a little more. Even people that didn’t know him used to say how infectious he was. If he once met you, he never forgot your name. I’ve heard a lot of people say this. They didn’t know Jimmy well but he always knew them.”

In 1942, the Marine high command created special “Raider,” units of elite, highly trained and mobile forces designed to fight light infantry amphibious campaigns peculiar to the terrain and nature of Pacific island battles. The “Carlson Raiders,” took their name for the unorthodox Brigadier General Evans Fordyce Carlson (1896-1947). By 1944, when Jim Arneberg had completed his training and was deployed, the nature and strategic imperatives of the battles changed dramatically. The Raiders were absorbed into the larger 4th Marine Regiment. The 4th Marines, combined with the 22nd Marine and the 29th Marine Regiment, was assigned to the 6th Marine Division that fought at Guam and Okinawa.

terrain and nature of Pacific island battles. The “Carlson Raiders,” took their name for the unorthodox Brigadier General Evans Fordyce Carlson (1896-1947). By 1944, when Jim Arneberg had completed his training and was deployed, the nature and strategic imperatives of the battles changed dramatically. The Raiders were absorbed into the larger 4th Marine Regiment. The 4th Marines, combined with the 22nd Marine and the 29th Marine Regiment, was assigned to the 6th Marine Division that fought at Guam and Okinawa.

Jimmy Arneberg saw extensive fighting during two crucial Pacific battles: the Second Battle of Guam (July 21-August 8, 1944) and Okinawa (April 1-June 22, 1945). More than 1,700 American soldiers died during the Guam operations. Jimmy Arneberg was instrumental in preventing another death when he saved the life of his buddy, Mr. Kagan. According to a Chicago Tribune report, “he saved the life of [his] friend, who had been hit by a flame thrower, by smothering the flames with his own body and then carrying the man to an aid station.”

Afterwards, when the late Mr. Kagan said he was going to recommend Jimmy Arneberg for a medal, “he really hollered at me.” Jimmy Arneberg incurred the bullet and shrapnel wounds at Okinawa. He was awarded the Purple Heart for his bravery. Friends and associates believe the two qualities that saved him during the war were his faith and his humor. He was not a man who feared death, they say, and so brought a certain equipoise to the horrifying circumstances of battle. “Jimmy was a good Catholic,” Mr. Pendergrast said. “He used to march Izzie off to Catholic church. Izzie would say, ‘Don’t you know I’m Jewish.’ He’d say, ‘Keep going, maybe you’ll become Catholic.”

After the war

The Japanese surrender in August 1945 ended the war. Military personnel were repatriated home in the early months of 1946. Jimmy Arneberg was 21 years old and ready for the next stage of his life. College was the logical destination. “The GI Bill was in effect,” Mr. Pendergrast said. “It paid all your tuition and seventy-five dollars cash bonus for expenses. A married guy got one-hundred and five dollars.”

Arneberg began his college career at Georgetown University in Washington. His close friend, Bob Hanlon, went to Notre Dame. “People always said he didn’t get along very well with [Notre Dame football coach] Frank Leahy and he transferred after a year to Loras,” Mr. Pendergrast said. Jimmy joined his friend Hanlon. He stayed only the fall semester at Georgetown. He left there and transferred to Loras College for the spring semester of 1947.

Arneberg began his college career at Georgetown University in Washington. His close friend, Bob Hanlon, went to Notre Dame. “People always said he didn’t get along very well with [Notre Dame football coach] Frank Leahy and he transferred after a year to Loras,” Mr. Pendergrast said. Jimmy joined his friend Hanlon. He stayed only the fall semester at Georgetown. He left there and transferred to Loras College for the spring semester of 1947.

Whether it was fate, circumstance, luck, or a special providence, the two helped take the small school in Dubuque, Iowa to the mountaintop.

Their arrival coincided with that of a new, ambitious coach named Wally Fromhart. Bud Noonan was a freshman at Loras College. He is also a historian of the school’s football program. “Loras was a long-time foe of St. Ambrose,” Mr. Noonan said. “During the 1930s and early 40s, Loras had a very difficult time with Ambrose. We went ten or 11 years without beating them. In ten of those years, we didn’t even score a touchdown. We were not used to Loras having a successful team.”

The 1947 team was different. Jimmy Arneberg helped lead a cohesive, disciplined offensive line that dominated the point of attack and opened gaping holes for Mr. Hanlon, the team’s star runner. Bob Zahren, the Mount Carmel product, played against Arneberg when the two were in high school. “He was the right guard and I was the left. He was probably the most talented player I ever played with,” Mr. Zahren recalled. “He was an exceptionally strong and very quick kind of player.

“In practice the linemen would pair off. I think Jimmy was the best player position for position on the team. He was very quick, very strong and very agile.”

Largely because of Jimmy Arneberg and Mr. Hanlon, Loras’ losing streak against their bitter rival St. Ambrose ended that year, in front of a record crowd of about 10,000 people, who watched the game at the school’s Rock Bowl. Loras won the game 20-6. The 1947 9-0 team was the last undefeated team in Loras’ history, although “We’ve had about 75 years of playing football,” according to Mr. Noonan.

watched the game at the school’s Rock Bowl. Loras won the game 20-6. The 1947 9-0 team was the last undefeated team in Loras’ history, although “We’ve had about 75 years of playing football,” according to Mr. Noonan.

Jimmy Arneberg received Associated Press small school All-American honors. Though he only played the one year at Loras, he was elected to the school’s Hall of Fame in 1975. The entire 1947 team was officially enshrined in the school’s Hall of Fame in 1988. Mr. Hanlon stayed and went on to become the school’s first professional player when he played with the NFL’s Chicago Cardinals.

It was as if, after realizing he had achieved his goal of athletic “perfection” in both high school and college, Jimmy Arneberg shifted gears again. Now he would focus on his scholarly ambitions and pursuits. After completing his sophomore year in the late spring of 1948, Jimmy Arneberg left Loras to enroll at DePaul University, the school from which he would ultimately graduate.

Coming home

Leo remained the centerpiece of this man’s life, social network and family foundation. The war and his academic pursuits meant that he would leave, but there was always a place for him at Leo. In 1951 he returned to the school as a coach of freshman football and varsity basketball. In basketball, the varsity teams were split into two distinct groups: the “lightweights,” for player five-feet, eight-inches and smaller, and the “heavyweights,” for anybody taller than five-eight.

In the mid-1950s, Leo continued as an elite football program. After coaching freshmen for several years, coach Arneberg assumed what many thought was his rightful place, when he was named head coach of the Lions varsity team.

Coach Arneberg posted six winning seasons in his seven years directing the football program. His first team was a transitional program. The Lions finished 5-4, but the coach knew he had a special talent in junior running back Ed Ryan. The 1956 team is one of the greatest in school history, but the season started off slowly with a tough loss against DePaul. If there were doubts about the new young coach, he put everybody’s fears quickly to rest.

Bob Foster, the Leo president, was the left guard on that team. Like many, he held a special regard for the coach. “It would appear on the outside that things didn’t really mesh between us,” Mr. Foster said. “I was very quiet and if you know anything about him he was very extroverted. He was my coach, and I would have run through a wall for him. He was a tremendous role model.”

Bob Foster, the Leo president, was the left guard on that team. Like many, he held a special regard for the coach. “It would appear on the outside that things didn’t really mesh between us,” Mr. Foster said. “I was very quiet and if you know anything about him he was very extroverted. He was my coach, and I would have run through a wall for him. He was a tremendous role model.”

For a great many people, football was the orbit around which their world revolved. The games were played on Sundays, as were the Chicago Bears’ and Chicago Cardinals’ games. The team drilled and practiced fiercely Monday through Friday. They attended a special Saturday Mass in preparation for the big game. Regular season games routinely drew five-figure crowds. Mr. Ryan recalls playing virtually year round. “On Saturday, you’d draw your equipment,” he says. The equipment was closer to armor, a protective sheath that turned players into warriors. The game was slower than today, more physical and the risk of injury was pronounced.

As a running back, the focal point of his team’s offensive attack, Mr. Ryan was subject to almost constant physical forms of abuse. He played through injuries, a pulled hamstring, busted ribs. During one game, the pain Mr. Ryan experienced was so unbearable that he nearly collapsed. “The chant in the stadium was: ‘Take out Ryan, the poor guy’s dying.’”

Years later, in a story that appeared in the September 1987 Chicago Sun-Times, Mr. Ryan revealed that he played his entire senior year hampered by a dislocated right arm. “Arneberg, with the help of Bears trainer Ed Rozy, devised a harness to immobilize Ryan’s arm,” the story said. “Ryan would cup his forearm over his stomach, where the quarterback would deposit the ball.”

Mr. Ryan earned the honor of the Sun-Times offensive player of the year. With his friend, Rich Boyle, the fullback who ran mostly inside, they formed a punishing two-way rushing attack. Leo’s biggest win was their 25-13 stomping of bitter rival Mount Carmel. Ryan scored on runs of 49, 25 and 82 and gained more than 200 yards. It broke a two-year losing streak to the hated Caravan.

Leo defeated Fenwick 27-13 for the Catholic League title. They dominated at the line of scrimmage and out-rushed the Friars 367 to 121. Three hundred and twenty-two of those yards were on the ground. They had an 18-1 advantage in first downs. Even so, Fenwick capitalized on some mistakes and strong special team play to take the lead, 13-7, late in the second quarter. Mr. Boyle scored in the waning seconds of the first half and the Lions never trailed again.

were on the ground. They had an 18-1 advantage in first downs. Even so, Fenwick capitalized on some mistakes and strong special team play to take the lead, 13-7, late in the second quarter. Mr. Boyle scored in the waning seconds of the first half and the Lions never trailed again.

Leo went on to defeat neighborhood rival Calumet 12-0 in front of a crowd of a 66,282 in the Prep Bowl at Soldier Field. The Lions capitalized on a special team’s mistake by Calumet, a snap that sailed over the head of the punter. Mr. Ryan scored on a four-yard touchdown run, capping a six-play, 34-yard drive. After a penalty negated a second touchdown by Mr. Boyle, Mr. Ryan scored on a follow-up play.

Leo finished with 313 yards, all on the ground; they limited Calumet to just 69 yards of total offense: 59 rushing and 10 throwing.

Coach Arneberg earned special plaudits for his humility and sportsmanship. Chicago Tribune sportswriter Ed Stone told the story:

“A stocky young man with the rugged features of a prizefighter walked into Calumet`s gloom-filled dressing room. The same (Calumet) Indians had just been beaten by Leo, and some of them were even in tears. But the visitor soon revived their spirits by just saying a few words. Then he left. He was Jim Arneberg, Leo coach, who was on his way to a victory celebration across the field. He had nothing but praise for Calumet, even though the City League champions were completely dominated by his Catholic League powerhouse.”

While that Prep Bowl championship team was his greatest accomplishment at Leo as head football coach, he also found the time to create the school’s legendary day camp and ran it for 11 years. It was a pioneering program designed to offer a physical and intellectual outlet for young kids.

His other teams were known throughout the city and especially the rest of the South side for their toughness, discipline, chemistry and refusal to ever give in. With the exception of a loss to Mendel, the Lions ripped off sixteen consecutive victories over the two seasons. The only down note to his coaching career was the 1959 team.

The yearbook description astutely, tartly summed up the year: “It was said that the Lions were held together only by tape and the desire to win.”

It was a different kind of experience. The team lost every game that year. They suffered heavy injuries and graduation losses. After a remarkable four year run where they won three conference champions and the Prep Bowl, a downside was perhaps inevitable. The team’s best player, fullback Bob Lake, was injured in the first game of the year against De La Salle. Mr. Lake did not dress against Mount Carmel and he saw only limited action the following two games.

Coach Arneberg rebounded by going 6-3 in 1960. Then in 1961, in his final year at Leo, coach Arneberg finished the season 4-3. The Lions won their first four games that year, but again injuries took their toll and the team dropped their last three games of the season. Perhaps most significantly, coach Arneberg’s final victory as coach of the Leo program came against the team’s greatest rival, Mount Carmel.

The precise reason for coach Arneberg’s departure from his beloved Leo has never entirely been provided. Mr. Foster said legend had it the coach had angered a powerful monsignor by asking for a salary increase. He and his wife, Marikay, had a growing family with four children. Perhaps he needed a job that paid better. The quick expansion of new school programs in the south suburbs were very enticing and difficult to turn down.

Coach Arneberg left Leo to take over the Homewood-Flossmoor program. Mr. Foster points out that coach Arneberg’s top lieutenant, his friend and former high school and college teammate, Bob Hanlon, replaced him at Leo. Even in his absence, the Leo program would bear his unmistakable imprint. The famed boys’ clubs and activities groups that he organized, ran and founded were pioneering acts of organizational brilliance.

teammate, Bob Hanlon, replaced him at Leo. Even in his absence, the Leo program would bear his unmistakable imprint. The famed boys’ clubs and activities groups that he organized, ran and founded were pioneering acts of organizational brilliance.

His influence and impact on his successors and disciples, men like coach Hanlon, Mr. Foster and Tom O’Malley was such that even when gone, his spirit would retain its hold over the school for decades to come.

He would coach at Homewood-Flossmoor for four years. “He was always the kind of guy who wanted to try different things,” Mr. Pendergrast observed. In 1965, he took his first college coaching job at Saint Joseph College in Indiana. It was at that time a small male school of about 1,300 students. He shook up the quiet, conservative culture there.

Mr. DeLisa was one of his first recruits. “I played quarterback at Mendel, and I heard of him,” he said. “Everybody had heard of him because of this man who’d do chin ups on the doorway while he was teaching. When he talked to you, he just mesmerized you. He was a great man to play for because of how he conducted himself.”

College campuses around the country were volatile places in the 1960s, but Saint Joseph was largely immune from the social turmoil. “You knew where he was coming from,” Mr. DeLisa said. “I remember one of the black kids went to talk to him and he said, ‘I don’t see color. I play the best. Whoever was the best was the best.’”

In 1967 he left Saint Joseph to take the athletic director’s job at Loyola Academy in Wilmette. His reputation preceded him. “The headmaster at Loyola was a Jesuit priest and he was walking with the football coach and the track coach,” Mr. DeLisa said.

“He says, ‘Where is this Jim Arneberg I’ve heard so much about? I want to meet him.’ All of a sudden out of nowhere this guy comes flying down the hall throwing body blocks into the garbage cans. ‘Father,’ the football coach says, ‘there’s your new athletic director.’”

In 1971 he returned to the South side to initiate the new sports program at St. Xavier University on 103rd Street. He was the school’s first men’s basketball coach. “At St. Xavier they were going to have [Chicago Eight defendant and anti-war protester] Abbie Hoffman speak. Jim was the basketball coach at the time. ‘Not in my gym,’ he said. ‘If they want him to speak, I’m going to shut off the lights.’ They called the cops and the cops were a couple of Leo guys. They just said, ‘Coach, would you please just turn on the lights because there’s no way we’re going to arrest you.’

He had a square humor, but many people found it endearing and it brought him closer emotionally to the people he was around. Mark Dwyer, a 1966 Leo graduate, recalled a story. “He had an interesting way of talking with people,” Mr. Dwyer said. “Once during intramurals, he was trying to goad a kid into taking a bet with him over which player would make the most shots. Of course, he wouldn’t bet money; he’d bet stuff like push-ups or something like that. There was a guy named Ed who was a legendary player in the Sabina house leagues who for some reason never played on the Leo team, just the intramurals. The kid took Ed, and of course coach Arneberg refused to bet because he knew he’d lose the bet.”

A new beginning

In 1974 he joined his friend Mr. De Lisa at Stagg High in Palos Heights as a dean. It did not take long for him to make his mark there either. “I was a teacher and coach. He didn’t coach when we first started. I was sitting in front and he was talking about whether we were going to have a study hall for the whole school. He asked whether the faculty wanted a quiet or talking study hall.

“But there were two teachers, one was a former Big Ten lineman and the other was a guy that pounded weights all the time. They said, ‘This is good. But when we’re in there, they can talk or do anything they want.’ So one more time, Jim says, ‘Does the faculty majority want a quiet one or a talking one?’ These two guys started to say again, ‘We don’t care.’ Jim started tugging on his belt. He stared them both down. ‘Do you two think you’re the only tough guys in this room?’ These guys’ eyes just went. ‘Because if you do, we’re going to step outside and settle this.’ They said, ‘We’re going to have a quiet study hall.’

“That was Jim’s first day at Stagg High School.”

Stories like that spoke to the complexity of his character. He projected an essential toughness, but many say his greatest strength was his ability to convince young people of their own value.

After a couple of years as a dean, coach Arneberg returned to the classroom to teach honors English classes; he also helped out the lower levels coaching football. “A freshman coach asked him to help him out,” Mr. DeLisa said. “There was one young kid that drove the rest of the coaches crazy. The freshman coach says to Jim. ‘I’m through with him. He’s too much of a pain.’

“Jim said, ‘Don’t. Let me work with him. Trust me he’ll be a running back.’ They were playing the biggest rivalry, Sandburg. We were stuck on the five-yard line and Jim says, ‘Let’s throw a screen pass.’ We throw a screen to this one running back and he goes 95-yards for the touchdown. Jim runs down the field, jumps into the end zone, tackles the kid and lifts him up because he was so excited.

“Football wise he was just brilliant. We were playing Tinley Park for the sophomore conference championship. A guy who played for Jim at Leo coached Tinley. Before the game I went up to Jim and said, ‘This is what Tinley does.’ Jim would say, ‘Try this out. It will work.’ The game was 14-14 going into the fourth quarter. I tried what Jim said and our fullback went 44 yards for a touchdown.”

“I was talking with the other coach after the game. He said, ‘Did I see Arneberg on your sidelines?’ He smiled and said, ‘I figured.’”

Final battle

He was generous, thoughtful and gracious. With his former Leo teammates, he founded the coronary club. They got together for dinner and played racquetball. He picked up every bill. Around his friends’ children, he was the classic great uncle: friendly, mischievous and funny.

It was during his time at Stagg that his cancer was first diagnosed. News of his illness stunned the Leo community. He was such an icon that many people figured he was indestructible. “Many of us thought that Jim would live into the hundreds,” Mr. Foster said.

Coach Arneberg was serene about his fate and condition. He found a divinity in the last years of his life, coping graciously and profoundly with the excruciating consequences of his illness. After his surgery for colon cancer, he helped to coach at Stagg, holding his colostomy bag. He still took his swims in the river.

“A person that wants to die has no fear. I was always aware of this,” Mr. DeLisa said. “We were driving, and my wife and Jim were in the front seat. He started talking about his sister and how lucky she was. My wife asked why and he said she was four years old and got hit by a streetcar. He said, ‘Just think, four years old and straight to heaven.’ My wife asked, ‘Is he always like that?’ I said, ‘It’s not an act. This man wants to go.’ All the guys were aware of that. He did not fear death at all. That’s the only man I can honestly say he wanted to go.”

James Arneberg, student, athlete, soldier, scholar, coach, husband and father, died at his home in Palos Heights on April 22, 1985. His last words were: “The lady is calling me. I’ve got to go.” At his funeral, the music began with the Leo fight song and ended with the Marine Corps hymn. Izzzie Kagan, the man whose life he saved during World War II, was one of the pallbearers.

He was survived by his wife, Marikay, his three daughters, Mary Catherine, Mary Carol, Mary Carmel, his son James, five grandchildren, and two brothers, John and Robert.

And by thousands of his natural heirs from Leo, Homewood-Flossmoor, Saint Joseph University, Loyola Academy, St. Xavier University, Stagg and Moraine Valley Community College and all points in between. The basketball program he founded at St. Xavier is now directed by coach O’Malley, and is one of the strongest in the country. Mr. DeLisa incorporated coach Arneberg’s ideas and theories on coaching clinics, organization and structure and adapted them for the five years his family ran the prominent Gatorade coaching clinics.

Mr. Foster, who played for him at Leo, eulogized James Arneberg the most pointedly, simply, yet eloquently: “He was unforgettable.”

I played for Jim for four years,worked at the Leo Boys Club, and was working at Stagg when Jim died in his apt. across the street from Stagg. The kids at Stagg loved him; he was tough but they knew he cared about them, and was concerned about how they fared after Stagg. They don’t have to be Leo guys or St. Joe guys; they just have to experience the man, to know. Kids just know!

I played for Jim in both football…2yrs and heavy weight basketball for 3yrs…he was good human being and a fantastic catholic…I lived near concisely park and he pick me up mornings for school at Leo…I think he use to drive his wife close to that area…..he said I was able to save the $.25a day so I could could on a date that next Saturday….bit the conditions were I had to attend mass before school in the chapel…I have done that most of my life…I went on to attend his nemesis st.Ambrose……that was 1950-1954 at Leo….it was a great time in my life…..Jim was a hero to so many students in those days……it was such a nice tribute….thank you…….jack miller ..dunwoody, ga.

I was at Leo 1950 to 1954

At that time there was a class for screw ups called “JUG”

One day I was in the “JUG” for some forgotten reason, but I had bought these big

combat boots at Franks, too big for my feet and I was in the first row. Jim came over to talk to me about football, a game for which I was too small. I think when he saw how big my feet were in those boots, he thought I might fit into the game. One of the Carlson’s Raiders, truly an exceptional man !

Jim Arneberg founded one of the finest boys’ day camps in Leo’s Boys Club. Finest because I still have fond memories of many summers spent there (1960-1968) learning how to swim. play ball and just getting along with others. The memory is so fond – that I recently returned to the camps’ location at the northeast corner of 143rd Street and 108th Ave, in Orland Park, IL to revisit the site – and now in its place were a couple of very large and expensive estates. Quite a shock, but that’s progress I guess. But, those homes could not squash my many memories of watching movies (The Birds and Nevada Smith come to mind), jumping on the trampolines, playing a lot of soft-cover baseball and so many road trips to roller skating, Brookfield zoo, bowling, and of course, Cantigny – the military museum in Wheaton. And guys like Jim, Joe Devine, Ray Bauer, and Bill Hanlon were great camp counselors. And at the helm was Jim – the nicest, gentlest, coolest guy of them all. Thanks Jim for what you gave us kids back then. I know that you are known for greater deeds and actions – but this one sits with me just fine. If anyone remembers, and wants to share a story or two, I’d like to hear from you. Rick Cieply rcieply@yahoo.com

Being the oldest son of Tony Kelly, I have more memories of Jim Arneberg than there is space for my comment. In October of 1951, when I was born, fathers were not allowed in the room when children were delivered but, had that been allowed at the time, I’m fairly sure Arne would have been next to my Dad, shoulder to shoulder, at the time of my birth. From that day forward to the time of his passing, Jim Arneberg was a big part of my life. Whether it was Leo Boys Club, to which I went for 8 years and worked at for another 2, to playing in one of his summer basketball leagues while he was at SXU or the combined celebration of his and my Dad’s 50TH birthday in the summer of 1975, he was a huge part of my life. My brother Tommy, who was around 5 years old at the time, once commented after Jim made one of his dramatic exits from our house “….that man is crazy!” He was everything described in the article but in addition he was, as the saying went in years past, a “Damon Runyon” character. A “one of a kind” man. When he was sick, my Dad, Bob Hanlon, Bob Kelly, Ike Mahoney, Rocky McCarthy (Ike and Rocky were childhood/neighborhood friends) and others would go visit Jim. They would shave him, make him as comfortable as possible and, ultimately, watched him die. As mentioned in the article, Jim passed on April 22, 1985. Less than eight (8) weeks later, on June 9, 1985, my dad passed away. To this day, I believe watching Arne at the end took a lot out of my Dad. Arne was a scholar, athlete, coach, mentor, etc but what he was best at was being a GREAT FRIEND and I’m so glad to see that his legacy is still with us almost 30 years after his passing:)

I can’t think about my Leo days without thinking of “Arnie”. They seem to be interchangeable. In class, when called upon, I always felt compelled to give the right answer for fear of what may happen to me if I were wrong. 🙂

My father played at DeLaSalle in the mid-40’s. As a team they were not very good. But individually my dad reaped many accolades. When it came time for me to pick a HS I wanted desperately to go to Leo. I did most of grade school at St. Thomas More, before finishing up at St. John Fisher [my parents kept making siblings so we were on the move a lot]. We used to flag or ride the bus to old Shewbridge Stadium and watch Leo play football. My best buddy in those years had his older brother go to Leo. And Leo played football like no one else on the Sout’side at the time.

But my father refused to let me go to Leo. Instead making me take the test to Rice. there was no way I was going to go to Rice after a bad experience with personnel therein while at SJF. Cut to the quick, I ended up at Evergreen Park HS. In 1964 two teams came out of no where in the old Southwest Suburban Conference vying to be champions. One was EP, who had no football history; the other, Homewood-Flossmore coached by Jimmy Arneberg. We were both 4-0-0 when we met at H-F’s field in 1964. Defense dominated the game as the first half was winding down. There was about a minute and a half left when….

Out of no where an over thrown pass was caught by a chugging end for EP in the back of the end zone. First blood. H-F had the ball after the kick off in decent field position. However, in trying to run a crossbuck HF’s QB handed the ball to an EP defensive guard twho ran into the end zone untouched. After the next KO HF was intercepted on the first play. One play later another pass found its way into the waiting arms of an EP receiver. In one minute thirty seconds the roof caved in on HF. EP scored another TD later in the game for the win and Team of the week in Chicagoland.

However, after the game I can never forget Mr. Arneberg coming across the field just to grab me and tell me how I was as good as my father was back in their day!. What opposing coach ever did such a thing!!! I was that defensive guard who took the ball out of the HF QB’s hands and ran the opposite way for a TD. What a thrill, right? No, the real thrill was Coach Arneberg grabbing me after the game to tell me I played like my father was know to have played. And I better understood why my dad did not want me to go to Leo: they won and DLS did not.

Best to all the Arnebergs. Semper Fi.

✝️

You were truly an inspiration

Now I know the whole story

Roy