Interviewed and Written by Patrick Mc Gavin 7/09

JAMES M. FARRELL ’61

All families have their own lore, a story, a tale, of interconnections or relationships entwined. James (Jim) M. Farrell likes to tell of the first ever date involving his mother and father.

Both of his parents were first-generation Americans. His paternal grandparents arrived from Ireland; his mother’s family came from Croatia. His father, Francis, was a policeman. “He went by Fran,” Mr. Farrell says. “People also called him Frank or ‘Red,’ because he had red hair. My mother was Amelia. She always hated that name, and I could never understand why, because I loved that name. So she went by Molly.

“A friend of [my father was] dating a nurse, and she fixed my parents up. Her father owned a meat market. It was a double storefront, a butcher store and restaurant. Typically people would go to the butcher store, order something and then go to the restaurant to eat. They go on this date, they go to the restaurant; my mother ordered a steak. They have the meal, enjoy it, and start thinking about desert.

“A friend of [my father was] dating a nurse, and she fixed my parents up. Her father owned a meat market. It was a double storefront, a butcher store and restaurant. Typically people would go to the butcher store, order something and then go to the restaurant to eat. They go on this date, they go to the restaurant; my mother ordered a steak. They have the meal, enjoy it, and start thinking about desert.

“My father says, Would you like something else. She says, Would you care if I had another steak.'” It was, after all, the Depression, and fine food was largely a luxury. It was the start of a beautiful relationship and the couple were wed and have five children. Young Jim was the third born, the second son, was born in 1944. His older sister is named Kathleen, and his two younger sisters are Maureen and Noreen.

Following the path of his older brother John, young Jim was introduced to summer camp culture as a young boy. He remembers going the first time when he was six years old. He spent part of the summer at Notre Dame Camp for Boys, in a beautiful, largely secluded island inlet near Kalamazoo, Michigan. “I got to meet kids all over Indiana, Michigan and Illinois. We even had kids come all the way from New York.”

His father was a cop, but it was his mother, formidable despite standing just five-feet, three-inches, who meted out the family discipline and code of behavior. At church, Mr. Farrell remembers, his mother demanded he pay the strictest attention to the priest and that his view never waver; he was never to look back, for instance, despite any noises that he might have heard from his friends seated behind him, for instance.

Tragedy struck in 1952. Jim’s older brother John died after contracting polio. “That was a killer for my mother,” he says. When young Jim was born, the family lived at 59th and Western Avenue. As a youngster, his family settled in St. Thomas Moore parish on 79th St.

Growing up in a major city in the Fifties was probably a halcyon. Everything appeared free, available and fun. Socially, events were shaped by parish culture. Like most South siders, Mr. Farrell was moored to a specific area. Rather than feel restricted or isolated, he felt liberated by possibility and a richness of life. “Everybody didn’t have cars and everything,” he says. “There were so many kids in your neighborhood you didn’t have to go anyplace. We still have pictures in the church basemen, and there were more than 100 kids on a single block. In Chicago it’s not what area are you from, it’s what parish are you from. Even the public school kids, that’s how they know where you’re from.

Mr. Farrell was moored to a specific area. Rather than feel restricted or isolated, he felt liberated by possibility and a richness of life. “Everybody didn’t have cars and everything,” he says. “There were so many kids in your neighborhood you didn’t have to go anyplace. We still have pictures in the church basemen, and there were more than 100 kids on a single block. In Chicago it’s not what area are you from, it’s what parish are you from. Even the public school kids, that’s how they know where you’re from.

“Going to high school when you go to meet kids from different parishes, there was a sense of the world just starting to open up.”

Fateful move

Every day decisions, small and profound, are shaped by single acts. “Why did I choose Leo?” he asks, pausing. Reflecting on his life, Mr. Farrell says had the family stayed at 59th and Western, it is likely he would have attended St. Rita. “I remember as a younger kid going [to St. Rita] for football games. Fortunately, we moved and I ended up going to a good school.”

Following his grammar school graduation from St. Thomas Moore, Mr. Farrell also considered Brother Rice. He remembers going to watch Leo play at Soldier Field, and it carried a distinctive hold. “That used to be one of the big things to go down to Soldier Field to see the Catholic championship game or the city championship [Prep Bowl]. You didn’t even have to be in high school, it was just always a super game.”

Culturally, his time was equally divided between St. Thomas and Leo “because the guys I hung around with at St. Thomas went to Leo.” Where you went to high school was important primarily because of sports. People went to the football and basketball games. Unfortunately we didn’t have baseball. That was my screw up because I loved to play baseball.” But even if you were not affiliated with a school team, there were plenty of opportunities to play baseball.

Culturally, his time was equally divided between St. Thomas and Leo “because the guys I hung around with at St. Thomas went to Leo.” Where you went to high school was important primarily because of sports. People went to the football and basketball games. Unfortunately we didn’t have baseball. That was my screw up because I loved to play baseball.” But even if you were not affiliated with a school team, there were plenty of opportunities to play baseball.

Mr. Farrell entered Leo the first time the winter of 1957 to take the entrance exam. He had an immediate rapport with the school, the building, the private space. Logistically, Leo had a direct access, a direct shot on the 79th bus. Some youngsters had a hard time assimilating the sometimes harsh discipline and rigorous techniques of the school’s Irish Christian Brothers. Not Mr. Farrell. It proved an almost natural continuation of the life lessons of home.

A half-century later, Mr. Farrell has no difficulty recalling the physical instruments of that discipline. “Br. McCullough had a board; Br. Hennessy had a drumstick that he used. If there were any indiscretions that you had, if there were errors on your homework or you didn’t have it prepared, [Br. Hennessy] give a little flick of the wrist and it’s amazing how much a drumstick hurts. Guys would be in class shifting their wallets from one side to the other. It didn’t help because he knew what was going on.”

By his own admission, Mr. Farrell was not a great or diligent student, but he had classes that he excelled and it dovetailed with the teaching programs at Leo. “I never really studied hard, but I got decent grades. I loved English and math. You’d always hear about algebra and how tough that was. I had Br. Hennessy for algebra. I realized it was like a puzzle: algebra is this side equals that side, so whatever you do this side you do the same thing to other side. Once I realized that, it wasn’t that hard. Some guys were puzzled by it, saying they’d never use it. I use [those principles] all the time, like when you’re working on your house, building something and you’re trying to get the angles to line up right.”

The brothers, Mr. Farrell says, were tough and demanding, but they were also men of character and colorful eccentricities, in manner or personal behavior. Several were not afraid to show a more personal, even humorous side. “You had to have a sense of humor if you were teaching a bunch of young boys.” He balanced his school work with forays into sports. Officially, he never played on a school team; he always tried out for the basketball team. There was tremendous competition for those slots, and he invariably was the last one cut. In the summer approaching his junior year, he began to grow. “I got taller but I didn’t put on any weight. I don’t care what I did, I could not put on any weight.”

show a more personal, even humorous side. “You had to have a sense of humor if you were teaching a bunch of young boys.” He balanced his school work with forays into sports. Officially, he never played on a school team; he always tried out for the basketball team. There was tremendous competition for those slots, and he invariably was the last one cut. In the summer approaching his junior year, he began to grow. “I got taller but I didn’t put on any weight. I don’t care what I did, I could not put on any weight.”

For extra money, he worked at a newsstand selling newspapers and magazines at 71st and Western. Newspapers formed the lifeblood of the city’s daily conversation. This was a robust era of a lively and varied bunch of newspapers. Chicago had four daily newspapers –Tribune, Daily News, Sun-Times and Herald-American. “I did it on the weekends, but it was a real bummer during the winters. It was cold being inside this newsstand with the oil heater going. Sometimes people would come by, get the newspaper and give you a tip. Others never thought about giving you a tip. When things were slow, I’d run across the street to the White Castle and go in there and get a cup of hot chocolate.”

Memorable days

During the summers, Mr. Farrell developed his growing, even addictive, pleasure to playing baseball. Leo didn’t field a traditional team, but that did not limit the possibilities. By the time of the most prominent young organization Little League came into existence, Mr. Farrell was past the cut off age. He played in a Babe Ruth League.

“We played over at 103rd and Westlawn. I was playing shortstop, and our coach was giving us fielding practice. He was hitting grounders and pop ups to us. He hit a pop up behind me, so I turned around and started running. The left fielder, his name happened to be Jim, too. He ran in. He played football at Leo. This guy Jim was a year or two younger than me but he was probably twice my weight. He weighed probably 230 pounds. I never heard him, and he didn’t hear me until the last minute.’

The two collided, and it was not a pretty sight.

“When they talk about seeing stars, I saw stars. He knocked me cold. I finally came too, and my manager was standing over me. He said, ‘Jim, are you okay.’ I said, ‘Yeah, except for the ring of stars going over my head.’ He said ‘I think you better go to the hospital.’ I was in the emergency room for about three hours before they sent me home. I went to see a doctor the next day and he told me I had a broken collarbone. He put a figure-8 bandage on me. He told me if you were a girl, we’d give you surgery to straighten out the bone. You’re a guy, you don’t have to worry about it. To this day m collarbone goes at an angle.”

Baseball also proved the source of probably the most surreal episode of his young life. In the summer preceding his junior year, Mr. Farrell was part of a team that was invited Joliet’s notorious Stateville penitentiary to play a group of inmates. “When you get there, they have the building out front. We had to change [into our uniforms]. It was sort of like going to an old swimming pool where you put our your clothes in a basket and get a tag. We’d put everything into a basket. They took us on a tour of the prison.

“Just going on the tour, you just knew you’d never want to have to go there. When you go in [the cell blocks], they’d have this circular structure and they’d have a tower in the middle with a guard. The guy could stand there and turn around and see all the cells. There was no privacy. We’d see these guys working out, lifting weights, in the yard.

“Just going on the tour, you just knew you’d never want to have to go there. When you go in [the cell blocks], they’d have this circular structure and they’d have a tower in the middle with a guard. The guy could stand there and turn around and see all the cells. There was no privacy. We’d see these guys working out, lifting weights, in the yard.

“It’s getting time for the ballgame. They had a nice field with stands. Then here come the prisoners. They don’t come in just helter skelter. They’re in single file. They come in, the first guy in line comes in and sits at the top in the first seat and each guy down until that line is filled. It was kind of weird or funny because the walls were very tall, about 40 feet high, but before you got the wall there’d be a drop off. One of the guys is batting and they’d hit a ball and we had this one kid playing left-field. He went there and just disappeared and then all you see is his mitt with the ball inside. It was a fun, strange experience. I can’t remember, but they had good ball players in the slammer.”

Historic day

In 1959, the White Sox qualified for the World Series for the first time since the reviled Black Sox betting scandal of 1919. On Oct. 2 that year, Mr. Farrell was startled one day when a message was delivered to his class that he immediately proceed to the principal’s office.

“I thought, ‘What the heck did I do.’ I get down there, and Br. Reagan said. ‘Your father called and he’s got a couple of tickets for the World Series. Go up there and get a buddy of yours, and I’ll call a cab for you.’ We took the cab, met my father, he gave us the tickets and we head over to the game. We’re in the upper deck of right center field watching the game. It’s my turn to go get the pop.

“I go out and stand in the line, and it’s taken forever. Finally I get up close and I hear a big roar from the crowd. I go walking back and my friend said, ‘Somebody hit a home run and somebody spilled a beer on Al Smith’s head.’ I said, ‘C’mon. What really happened?’ I saw it like most people like seeing a picture of it. I kept my stub and a couple of years ago I got Billy Pierce to sign it.”

Mr. Farrell was one of 47,368 fans at Comiskey Park that day. The Dodgers beat the White Sox 4-3. Charlie Neal hit two home runs for the Dodgers, including the one that resulted in Al Smith being soaked with beer.

A new dawn

If the times were changing, Mr. Farrell says there was no immediate indication. It was the start of a new decade, the Sixties, but this was before the convulsive changes and cultural confrontations that profoundly shook up the country. Chicago was the epicenter of the changes in popular culture, especially music. Mr. Farrell did not pay particular attention to changes in music and culture.

confrontations that profoundly shook up the country. Chicago was the epicenter of the changes in popular culture, especially music. Mr. Farrell did not pay particular attention to changes in music and culture.

“I had a friend who can still remember all those songs. He’d always be calling the musical stations that had the quizzes and he could name them just by hearing a few notes. I envied those kids on ‘American Bandstand’ that could dance. I considered myself fairly athletic and coordinated, but I had two left feet whenever I tried to dance. The first thing I remember about the Sixties was the Cuban Missile Crisis [in October 1962].

Mr. Farrell graduated from Leo in 1961. He was not entirely certain of the right direction for the next phase of his life. He decided on college, originally spending a year at St. Mary’s College in Winona, Minnesota. “I didn’t really have a clue about what to do next. I probably would have been better off going to a trade school,” he says. He transferred after after his freshman year at St. Mary’s to attend Loyola University on the North Shore. He was on campus on the fateful day of Nov. 22, 1963, the day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. He heard about the shooting from a fraternity brother. “I told him to quit goofing off,” he remembers. Once the news settled in, he headed to the school’s Student Union.

College was not quite his métier. “I was a horrendous student and I finally dropped out,” he says. He spent a summer delivering beer and soft drinks. He tended bar at an establishment his father owned at 59th and Kedzie. “I worked there, came home one day and looked through my mail,” he said. He received the government letter he knew was inevitable: his draft notice. By quitting school, he’d given up his college deferment.

“I figured it was just a matter of time. I finally called the draft board to get my number pushed up so I didn’t have to wait forever. They told me: ‘We don’t have to push your number up.’ Shortly thereafter I got my letter. The choice was either to get drafted or to enlist. If I enlist, I’m going to be in three years rather than two. I wound up getting drafted.

If many dreaded what awaited, Mr. Farrell was not one of them. His background was uniquely suited to the dictates of the Army. “Having a good Catholic education with all the discipline helped,” he says. “I had discipline at home, I had the nuns in grammar school and the Irish Christian Brothers at Leo.

“Basic training was a piece of cake.” He performed his basic training at Fort Campbell in Kentucky. “In basic, they give you a whole battery of tests to find out what you’re going to wind up doing in the service. Then you go in and talk with somebody. I went in and this guy says: ‘Are you going into OCS [officer candidate school]?’ I said, ‘No.’

‘Why?’

‘Because they didn’t ask me.’ He said, ‘If they asked, would you want.’ I said, ‘yeah.’ He says, ‘They were looking at your test and they didn’t turn it over. They were missing about fifty or sixty points on your score and you easily qualified.’

“I wound up getting lined up to go to Infantry OCS. After basic, you go to advanced individual training [AIT], and they sent me to Fort Knox, Kentucky for armor training. I got called into see the first sergeant. He said they lost my results and I had to go back before the board. I thought, I’m going to Vietnam, I don’t want to be stuck in one of those great big metal boxes with RPGs [rocket-propelled grenades] coming at me. I wanted to stay with the infantry. This time I just answered the questions the way I wanted–I was irritated with the service by now. I thought it would ruin my chances, but [the first sergeant] said they found my results and I’d be going into Infantry OCS. That meant I was going to be in for three years.

In Vietnam, Mr. Farrell obtained the rank of captain. Like most soldiers, he honed his survival instincts. He commanded a platoon of approximately 40-80 men. He was assigned to the 25th Division. The unit was involved in some of the war’s fiercest fighting with North Vietnamese Army (NVA) regulars. He spent seven months in the field and was awarded the bronze star. As part of his OCS training in Fort Bennington, Georgia and Fort Bragg, North Carolina, Mr. Farrell became a specialist in television and radio operations. For the duration of his Vietnam service, he was assigned to head a television and radio station in a harbor of Nha Trang.

In Vietnam, Mr. Farrell obtained the rank of captain. Like most soldiers, he honed his survival instincts. He commanded a platoon of approximately 40-80 men. He was assigned to the 25th Division. The unit was involved in some of the war’s fiercest fighting with North Vietnamese Army (NVA) regulars. He spent seven months in the field and was awarded the bronze star. As part of his OCS training in Fort Bennington, Georgia and Fort Bragg, North Carolina, Mr. Farrell became a specialist in television and radio operations. For the duration of his Vietnam service, he was assigned to head a television and radio station in a harbor of Nha Trang.

Letter about a friend

“You see these movies about the Second World War and the South Seas, that’s what this was like. We had a radio station just outside of Cam Ranh Bay. I get a letter from my mother that said a friend of mine was stationed nearby. One day I was taking a Jeep ride, I go to Cam Rahn Bay to the Air Force Base to find out about my friend. His nickname was Magnet Ass because he got hit so many times. He was shot down once. He told me he was coming down in his parachute and he sees all of these guys in black pajamas running. He hits the ground, he’s got his pistol, and he hears somebody yell, ‘Get your ass in here.’ It was the door gunner of a helicopter. He didn’t have to be asked twice. This was George Muellner. He lived a few houses down on the other side of the street from me. We went to St. Thomas Moore and Leo together. He also graduated from Leo in ’61 and ended up being a three-star general.

“It was nice to see somebody from home.”

Mr. Farrell returned to the United States, via California, in 1970 and he completed his military service at Fort Devens in Massachusetts as a counselor at the military stockade. He faced what he calls one of the most difficult decisions of his life, of deciding whether to remain in the military or return to civilian life.

“One of the hardest things I ever did was to get out. There are a lot of nice things about [the military]. I didn’t like the war. Vietnam was still growing strong. It was going really strong when I was going there. I just didn’t like being in a war. I have no use for [television broadcaster] Walter Cronkite. We were winning the war, we should have won the war. The Democratic party stuck it to us, with Cronkite saying the war was over. We won all of our battles. The war was lost at home.”

Mr. Farrell returned to Chicago and began his post-military life working for the International Business Machine (IBM) Corp. He worked at offices in Evanston, Palatine and the Loop. He worked originally in hardware before moving to the quickly-growing software field. Inspired in part by a welcome home parade for Vietnam veterans in 1980, Mr. Farrell undertook a meticulous effort to reach all of the officers that served under him in Vietnam. In the end he found seven of the eight men, a great many of them pleasantly surprised and honored by his efforts to make contact.

The computer industry was both fundamentally altered by radical changes in digital technology and the advent of the Internet. Mr. Farrell’s run at IBM came to an end after his position was eliminated in 1993. By then, he had shifted focus to caring for his now elderly parents. “I became a kind of professional caretaker,” he says. His father Francis passed away in 1993 at the age of 85. His mother Amelia reached the age of 90 before succumbing to illness in 2004.

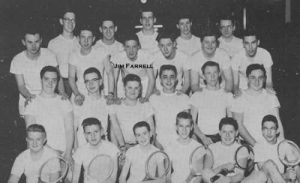

Mr. Farrell remains a central part of the Leo community. He was elected to the school’s prestigious Hall of Fame in 2000. He is the director of the school’s alumni association. He was named Leo’s Alumni Man of the Year in 2003. When he graduated in 1961, he was part of a class he estimated at 230 people and a school enrollment that was approached 1,100. Today, those numbers are just a fraction of that. He is entrusted with maintaining those times and memories. Like the Irish Christian Brothers that shaped him, Mr. Farrell is a serious, highly devout man; he also shows a playful and humorous side when the moment calls.

The school’s alumni banquet is a marvel that draws former students from throughout the country. Mr. Farrell helps orchestrate the logistically daunting yearly event. “We’re thirty years older than Brother Rice but they have a lot more alumni than us just because they’re such a bigger school. [Mt.] Carmel is the only one that can rival us, but they’ve been around for more than a 100 years.”

It is a way of course to remain connected but also to reflect on a life. The order of Leo had profound personal implications that helped set a tone, a principled and orderly way to live and work. “You knew what the rules were, and as long as you played by the rules, you were fine.

Speak Your Mind