Interviewed and written by Angelo Banadano, Edited by Patrick Mc Gavin

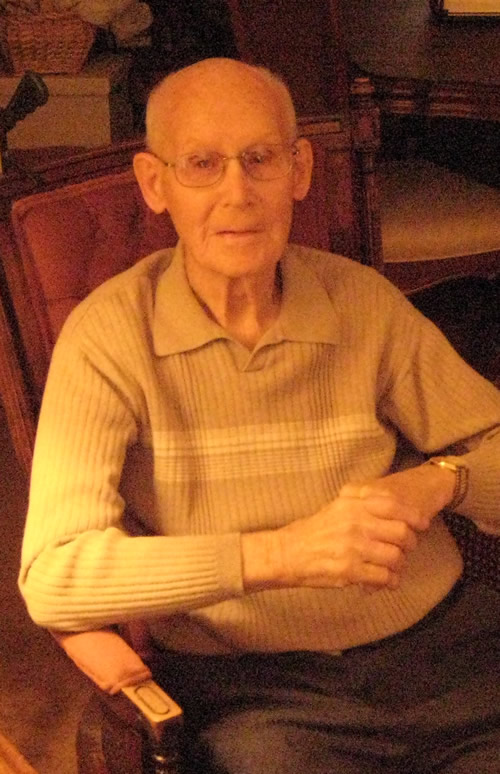

JOHN DALEY ’38

A foundation of literature, art and culture, man’s essential nature, his being, is predicated on the quest. That “search,” as it were, takes on many forms, private and public, inner and outer that moves through space and time. It is both physical and intellectual that forms a narrative, a story, of a man’s life, his thoughts and preoccupations. In our imaginative sympathy for the individual, we recognize instinctively that people belong both to history but also to themselves. Their connection to people, places and events brings an emotional solidity, of chapters or episodes from the life that help us understand better, more completely, the world around us.

John Daley has such a perspective. He is a living embodiment of the volatility and severe disruptions of 20th century American life. His story of struggle, experience, adventure and achievement is not his of one alone, of course. In the dramatic curves and sensations of his life, Mr. Daley gives a tangible meaning to many of the transformative experiences of American life: the Depression, the New Deal, World War II and the modern age. His story encompasses a range of dovetailing identities–student, athlete, worker, warrior, husband, father and corporate chieftain. Mr. Daley fits a discernable type, familiar from the time, of growing up and coming of age in a large, close-knit South Side Irish-American family.

His formative experiences intersect with another important and prominent cultural, religious and social institution: Leo High School. The experiences of Mr. Daley form a recurrent pattern of many friends, colleagues and classmates of the era that marked a time of service, duty, sacrifice and labor. His story features its own twists and curves and bears telling.

Origins

It is one of the most famous openings in the history of American literature. “I am an American, Chicago born (Chicago that somber city), and I go at things as I have taught myself,” Saul Bellow wrote to introduce his eponymous hero in The Adventures of Augie March. All stories have a beginning, however modest or inchoate. That opening describes any number of people. Mr. Daley was born in 1920, the second of six children, five boys, one girl, who grew up at 105th and Torrence, in the city’s historic South Deering neighborhood. The neighborhood stretched the far southeastern ring of the city’s 77 communities.

It is one of the most famous openings in the history of American literature. “I am an American, Chicago born (Chicago that somber city), and I go at things as I have taught myself,” Saul Bellow wrote to introduce his eponymous hero in The Adventures of Augie March. All stories have a beginning, however modest or inchoate. That opening describes any number of people. Mr. Daley was born in 1920, the second of six children, five boys, one girl, who grew up at 105th and Torrence, in the city’s historic South Deering neighborhood. The neighborhood stretched the far southeastern ring of the city’s 77 communities.

The neighborhood symbolized the poet and journalist Carl Sandburg’s famous observation of the “city of broad shoulders.” The latitude and longitude was 41°42.6′N 87°33.6′W. South Deering was an industrial zone dominated physically by Lake Calumet and culturally by the existence of the region’s first steelworks, Joseph H. Brown Iron and Steel company that was founded in 1875 and later renamed the Wisconsin Steel Works. The neighborhood was heavily white European ethnic.

The ruling activities were sports and the church. With his brothers, Mr. Daley played sports with a rigor and devotion that established the daily rhythms and physical activity of the neighborhood. “Baseball, basketball, football, I played them all,” Mr. Daley said. Sports were an important measure of a young boy growing up. As Irish immigrant families became more assimilated to American culture and society, sport was a gateway with an emphasis on dedication, discipline and desire that proved an important crucial early life lesson. Growing up, Mr. Daley said, he believed that toughness was not discernable virtue worthy of praise though a culturally ascribed, inbred attitude that flourished in his family and larger South Side Irish neighborhood.

If Wisconsin Steel Works established the industrial base of the South Deering neighborhood, St. Kevin’s Church established the civic and cultural life. The steel works and the church were built simultaneously in 1884. The Daleys lived literally steps from the church. In 1925, when Mr. Daley was five years old, a new, larger space was built to include a new church, a hall and rectory. The Daley children each attended the school through the completion of eighth grade. Following his graduation from St. Kevin’s in the summer of 1934, Mr. Daley faced a dilemma of where to continue his education. In one of those fortuitous actions combining fate and as it turned out, luck, Mr. Daley settled on the advice of his older brother and cousin who insisted he attend Leo High School.

Sure, it made sense; Leo was a haven for South Side, Catholic Irish émigré families. Built in 1926, Leo had something its rivals Mount Carmel or St. Rita did not. It was a newer, more dynamic school whose own history was very much a work in progress. Men like Mr. Daley were put in the unusual position of establishing and shaping the reputation, name and honor of Leo.

Historical discord

Mr. Daley, his family and friends, did not, of course, live in a vacuum. He entered Leo in the fall of 1934, about a year and half into the presidential administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt. The 1929 stock market crash ruptured an already fragile American economic and social order, plunging millions into unemployment and hastening the Great Depression. Family, service and religion were the bulwarks that provided some sanctity and stability from the nightmarish social and economic order.

Upon his arrival at Leo, Mr. Daley found a great release and order in organized sport. He had played sports constantly growing up. The organized teams at Leo provided his entree into team activity. He had the natural attributes of the athlete, wiry, quick, determined and focused. The campus at Leo, 79th and Sangamon, was quickly transformed into his home away from home. His friends and family called him Jack. After coming up through the underclass ranks, Mr. Daley earned a spot on the varsity in his junior year.

That nurturing and development process set the stage for a memorable and epic moment of his senior year, beginning in the fall of 1937. By now, Mr. Daley filled out physically and had a natural poise and feel for the game. He was a two-way starter at two crucial positions, quarterback and safety. In that era, communication between the coaches and players was fairly primitive. The quarterback and safety effectively became the coach on the field. They set the tone on both ends, creating order, shouting encouragement, telling teammates of where they should line up and affirming their responsibilities.

That nurturing and development process set the stage for a memorable and epic moment of his senior year, beginning in the fall of 1937. By now, Mr. Daley filled out physically and had a natural poise and feel for the game. He was a two-way starter at two crucial positions, quarterback and safety. In that era, communication between the coaches and players was fairly primitive. The quarterback and safety effectively became the coach on the field. They set the tone on both ends, creating order, shouting encouragement, telling teammates of where they should line up and affirming their responsibilities.

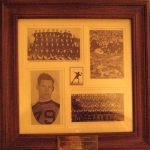

Mr. Daley was part of the first wave of great players at Leo, joined by star running back Johnny Galvin, Tommy Martin and Jimmy Cooney. They embodied a team-first approach given to unselfishness, dedication and camaraderie that culminated in the highest achievement. After suffering a loss in an exhibition game to begin the year, the Lions routed the Catholic League. Galvin was explosive in the open field. Football, as practiced between the two world wars, was a very punishing and physically aggressive game. Teams rarely passed. Common of that period, Mr. Daley ran most of his team’s plays out of a running-dominated formation. It was typically considered a short punt formation, the quarterback lined up several yards behind the center.

In a precursor to what became the famous and feared wishbone offensive attack, Mr. Daley took a direct snap from center and had the option of running the ball himself, throwing it or handing off directly to one of his running backs or pitching at an angle, trying to create mismatches with the defensive alignment. Galvin was the star, a fierce athlete who astonishingly played most of the year with an injured shoulder. Mr. Daley was the conductor. The Lions’ 6-0 shutout of St. George in the Catholic League championship punched the team’s ticket to historic Soldier Field for the “Kelly Bowl” (named after the city’s mayor, Edward Kelly) that matched the champion of the city’s public league and Catholic League.

In 1937, Soldier Field was a much different physical space, an open-ended structure that allowed overflow crowds for historic boxing matches (like the famous Jack Dempsey/Gene Tunney rematch that drew 104,000 people in September, 1926). Leo’s showdown with Austin High produced its own history, drawing 120,000 fans on the Friday after Thanksgiving, believed by historians and credible accounts the largest assembled body to ever watch an American sporting contest. The west side school Austin was the pride of the Public League boasting a star running back, Bill DeCorrevont.

Tunney rematch that drew 104,000 people in September, 1926). Leo’s showdown with Austin High produced its own history, drawing 120,000 fans on the Friday after Thanksgiving, believed by historians and credible accounts the largest assembled body to ever watch an American sporting contest. The west side school Austin was the pride of the Public League boasting a star running back, Bill DeCorrevont.

The score was zero-zero after the first quarter,” Mr. Daley said. They had a great running back who eventually went on to Northwestern. I remember in one play, when I was on defense, playing safety, he was running in the open field and I thought I had a great shot at him.” Their bodies met in full force.

“Well, he put his shoulder down and he knocked me backwards about ten yards. I was about 151 pounds, and he was almost 200.” The play symbolized the essential imbalance of the two teams. Leo controlled the clock with their running game in the first half, but they could never quite get past the talented and tough Austin defense. Austin’s greater size and speed finally wore down the Lions. The Tigers scored two second-quarter touchdowns to lead 13-0 at the halftime break. Austin added a touchdown apiece in the third and fourth quarters. They beat Leo 26-0.

Leo lost, but the 1937 team marked the breakthrough for the ostensibly new school that was just beginning its second decade of existence. The team proved Leo had the capacity to compete at any level, and the team presaged the dominant Leo teams that would follow in the 1940s. The team’s success helped shape the early identity of Leo as a tenacious, disciplined and top-notch school that was an emerging force to reckon with. More than seven decades later, Mr. Daley cherishes the memories of the game if not the result.

Public works

With a large family to help support, Mr. Daley eschewed college in order to work. Following his graduation fro Leo, he decamped for Idaho, where he worked for the Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC), a public relief works program instituted in 1933 by the Roosevelt Administration under the aegis of the New Deal to spark a dormant economy and help coordinate public land conservation. The workers lived in spartan conditions, similar to military “boot camps,” were subject to strict age limitations, but the experience sharpened Mr. Daley’s work ethic. “I made $30 a month,” he said. “I sent $25 of that to my family.” In all, Mr. Daley spent six months in the CCC; his primary responsibility was cutting sagebrush. On weekends, he traveled to Boise, living in a YMCA (the bed costs a quarter a night).

The CCC was one of the most popular New Deal programs though by the end of the decade, the economy started to recover and job opportunities opened up in the private sector. The outbreak of war in Europe shifted the program’s emphasis to national defense and forest preservation. In 1939 Mr. Daley returned to Chicago. In another fortunate example of excellent timing, Mr. Daley caught the attention of an attractive young neighborhood girl, Ellen.

The CCC was one of the most popular New Deal programs though by the end of the decade, the economy started to recover and job opportunities opened up in the private sector. The outbreak of war in Europe shifted the program’s emphasis to national defense and forest preservation. In 1939 Mr. Daley returned to Chicago. In another fortunate example of excellent timing, Mr. Daley caught the attention of an attractive young neighborhood girl, Ellen.

After two years of courting, the couple was married on Thanksgiving of 1941. By then, American participation in the European war appeared inevitable. Two weeks later, Japan launched a surprise aerial attack at Pearl Harbor and President Roosevelt declared war against the Axis powers of Germany and Japan. In 1942, with Ellen pregnant with their first child, Mr. Daley was drafted.

He spent his basic training in Oregon and California. Mr. Daley shipped out with the 96th Infantry Division, also called the Sustainment Brigade. Mr. Daley was part of a 200,000 American fighting division that combined with a Filipino guerillas staged a crucial landing invasion at the gulf of Leyte against the occupying Imperial Japanese Army that launched Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s Philippine Campaign of 1944-45.

The landing was the largest amphibious assault to date by American fighting forces. Begun by minesweeping operations, fighting broke out Oct. 31, 1944 and lasted through Dec. 31. It marked both a decisive turn for the Allied forces and a personal triumph for Gen. MacArthur, forced to retreat two years earlier from the Philippines. Mr. Daley performed with valor and discipline during the three-month conflict. During one incident, he participated in a rescue operation that repelled a Japanese frontal attack and enabled a group of fellow infantrymen to escape from a trapped hole. During the near hand-to-hand combat, Mr. Daley incurred serious injuries to his hand and arm after a thrown grenade stuck his upper body, rolled down his arm and discharged. Mr. Daley was one of a reported 15, 584 casualties sustained during the operation. Mr. Daley was awarded two Bronze Stars for valor his actions.

Mr. Daley recuperated from his injuries at a Philippine hospital. The decisive Allied victory in the Philippine campaign, dislodging the occupying Imperial Army forces, reduced significantly Japan’s fighting capacities and air power and precipitated the decisive shift toward the invasion of Japan’s home islands, the most crucial of which Mr. Daley volunteered. Now fully recovered, Mr. Daley was part of a massive Allied force that seized the Ryukyu Islands of Okinawa, some 350 miles from the Japanese mainland. Launched on March 26, the land battle last three months.

By the end of the air campaign on June 23, Allied forces inflicted devastating losses the Imperial Army never recovered from. Following the atomic bombings of two Japanese cities six weeks later, Japan surrendered. Reflecting back on his military service, Mr. Daley said, proudly: “I think I did help my country, and I was glad to do it.”

Homeward bound

Following his discharge from the Army, Mr. Daley was repatriated home. After the miseries induced by the Depression, the American entry into the European and Pacific war had mounted an economic recovery. The war produced a “second industrial revolution,” for manufacturing materiel, ships and planes that significantly improved the fortunes of companies like Wisconsin Steel Works.

Mr. Daley returned to a much different country, growing, prosperous and accorded a much greater social mobility. The almost insatiable demand for steel in developing industries, the rise of automotive culture and the growing of new and emerging communities turned Wisconsin Steel into a thriving company. Mr. Daley made a seamless transition from soldier to civilian worker. At Wisconsin Steel, he quickly rose to the job of inspector.

The first son of Mr. Daley and his wife, Ellen, Jackie, was three-years-old upon his return home. With the birth of a second son, Kevin, the family lighted out for the developing suburban community of Lansing. Even so, the family retained its connection to Leo High School. Both of Mr. Daley’s sons graduated from the school. Jackie earned distinction as both a student and athlete. In 1960, he received the school’s outstanding student/athlete scholar prize. He attended the Miami University, in Oxford, Ohio.

The first son of Mr. Daley and his wife, Ellen, Jackie, was three-years-old upon his return home. With the birth of a second son, Kevin, the family lighted out for the developing suburban community of Lansing. Even so, the family retained its connection to Leo High School. Both of Mr. Daley’s sons graduated from the school. Jackie earned distinction as both a student and athlete. In 1960, he received the school’s outstanding student/athlete scholar prize. He attended the Miami University, in Oxford, Ohio.

Mr. Daley worked for 35 years at Wisconsin Steel Works. Following his retirement, Mr. Daley and his wife traveled the country and experienced other parts of the country. For a time they lived in Arizona for the more agreeable weather conditions. For many, the South Side is a world unto itself. Even in leaving, many find almost impossible to leave it behind. In 1986, the couple returned to Lynwood. The Daleys are approaching their seventh decade of marriage. They have two grandchildren and attend church every week.

“I met a lot of nice at Leo,” he said. He remains a man of different masks who responded to a call of duty and carried that through the remainder of his life.

In Bellow’s opening to his great novel, the protagonist continues his line of thought:

“go at things as I have taught myself, free-style, and will make the record in my own way: first to knock, first admitted; sometimes an innocent knock, sometimes a not so innocent. But a man’s character is his fate, says Heraclitus.”

His character has been resolute, firm, daring and open. He has left a mark.

Speak Your Mind