Interviewed and Written by Patrick Mc Gavin 10/09

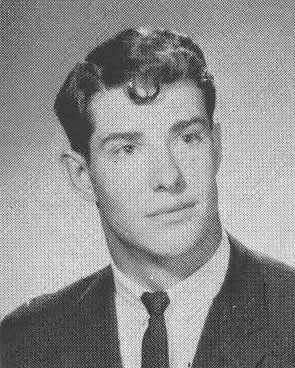

MARK DWYER ’66

“Whoso would be a man,” Emerson said, “must be a nonconformist.” The story of Mark Dwyer is of a man who’s ostensibly gone against the grain. Not every time, mind you. But he found his own road, his own path and took the plunge. It was a way for him to spread his wings and make, no pun intended, his mark. He arrived in a family already demarcated by strict lines, of history and the period. “I was the seventh of eight children,” he begins. “My dad was John Dwyer Sr. He was a doctor. My mother’s name was Mary Lynch. Her parents came from Ireland by way of England. I know my mother was a teacher; my dad was in medical school when they met. They were married in the early thirties. My oldest brother John, who passed in 2005, would be 77 today.

“There’s a before a war family and an after the war family. My dad spent five years in the war. He was a flight surgeon in Burma. The three youngest boys, Paul, Mark and Dennis, were born from 1946 to ’49. Right there that creates two different families.

“At the time there were no specialties. My father and another doctor delivered thousands and thousands of babies on the South side. Today, I still meet people and they say, ‘I knew your grandfather.’ I’d asked them how, and they said he delivered them. I’d say, ‘No, that was my dad.’ There’s hardly a place on the South side I go where I don’t run into somebody that my dad didn’t deliver. He was a physician/surgeon. He did any kind of surgery.

“During the war, my mother was by herself, and the ages of the kids then went from high school to grammar school. They lived in Sabina, and everybody got together. Fortunately she had some friends that were in a similar situation. One of these friends came from a family that owned a meat market. Everything back then was rationed. Because of that connection, my mother had a lot of things that other people didn’t. I can’t verify this, other doctors took over his patients and practice and I guess they must have given my mother some percentage of the business.

“The way I look at it, when my father came back from the war, he was tired. The older ones say the war changed him tremendously. My oldest brother was fifteen years older than me. That’s a big change in what goes on in the world. I was born in November of 1947. We lived in St. Sabina, at 79th and Ada. That was in the old days when everything centered on the parish. We had a gigantic community center and you never left the neighborhood. They had a Sunday evening dance where everybody from the South side would go. A lot of times it turned into a big brawl; you’d get people from the different parishes or high schools, somebody didn’t like Rita guys or Carmel or even Mendel back then. It all meshed together.

“Basically I played basketball at St. Sabina. It had a really strong basketball tradition in grammar school [Catholic Youth Organization]. They always had at Sabina a number of tournaments for all Catholic league schools on the South side. They had one, it was called I think the Sabina Tournament, and the school had never won in all the years it was in existence. The year I was in eighth grade, our team won and everybody went wild. They used to have the championship game for this tournament either before or in between the games for the AAU, the adults’ amateur athletic union. The gym was filled with people, and they all went crazy. You’d have school until two or three in the afternoon and then immediately you went into the gym. There was always something going on: roller skating, running, indoor ball. You had sixteen-inch softball tournaments at 77th and Racine. They kept you busy.”

Different path

Mark was the only one of the eight children not to attend St. Ignatius. He wasn’t crazy about making the long commute to that school. The cultural attitudes of the place irked him. He thought the school was infused with a smugness and entitlement that made the school and its environment uncomfortable. Leo was his destination. Also the world was changing, rapidly, and it was sometimes difficult to get your bearings. The conformity of the Eisenhower years was now pushed aside by the bold adventurism and individualist imperative of the Kennedy new frontier. Still, part of what separated him from his peers as well was the particulars of his family life.

“My father didn’t think Chicago during the summer was a safe place to be because of health reasons. Polio was a big thing at that time. My family always had a summer home in Long Beach, Indiana, right outside of Michigan City. It was sixty miles away [from the South side], but you’re in a different country once you’re there. The air was cleaner. We’d leave on Memorial day and we wouldn’t come back to Chicago until the day after Labor day to come back to school. Up there, you very seldom had to put on shoes, just once a week to go to church. You’re always in a swimming trunks or shorts.

Beach, Indiana, right outside of Michigan City. It was sixty miles away [from the South side], but you’re in a different country once you’re there. The air was cleaner. We’d leave on Memorial day and we wouldn’t come back to Chicago until the day after Labor day to come back to school. Up there, you very seldom had to put on shoes, just once a week to go to church. You’re always in a swimming trunks or shorts.

“Our next-door neighbor up there was Frank Leahy, the Notre Dame football coach. They had a family like the old Irish did, where all the kids were the same age. It was almost identical, kid for kid, in our family, so they were our summer friends and we had a lot of fun with them. They had a gigantic foot lawn with all the kids where we’d play football. He’d come out and try and coach us. We were the lads. They had a huge basement with all the nine or ten [Notre Dame football] national championships.

“My older brother went to Notre Dame, and all the football players you knew about, like Paul Hornung, were always around. I met all of these guys. My brother hung around with them, they’d be at our house and my mom and dad would feed them on the weekends. Those were our summers, and very seldom did we spend any time in Chicago. Except when I got into Leo and I had to start going to summer school.

Standing out

In the fall of 1962 Mr. Dwyer entered Leo. He was small, scrappy and avid for experience. “When I went into Leo, I could measure in for lights,” Mr. Dwyer says. “I was barely five foot. Then one summer, everybody told me I got mononucleosis, I came back and I was almost six foot. Then I was six foot, three. I went from lights to where I had to have to play [heavyweights, of players five-feet, eight-inches and taller].

“In grammar school everything centered around the parish, and the people in the neighborhood, you couldn’t screw up because somebody was always watching you. It was an extended family. The parents gave implied authority of discipline to kids in any way they determined was necessary. If somebody did to one of my kids what was done to me, either grammar school or high school, there’d be a lawsuit. At the time, I hated it, but I think I realized that was the nature of the beast.

“When I took the test at St. Ignatius, I was struck at it being a very old school: metal staircases that you had to be careful because it was worn thin. It was an ornate building in a tiny neighborhood. I don’t recall taking an entrance test at Leo. I went there and I thought it was a more modern building, totally different from grammar school. Sabina was three stories. There were lockers, different styles of room, and it was kind of intimidating. When you’re twelve or thirteen, when you go there the first time, because even if you might have walked the school previously with friends of yours, they’re in different classes now. You’d see them periodically during the day.

“Most of my friends went to Leo. Ignatius would take two or three kids out of a school from the South side. I felt more comfortable [at Leo], because I did go to things at Ignatius with my brothers. I don’t know if they were that much different than Leo. Whether it was any better than Brother Rice or Rita or Leo, but any school you choose to go to, it depends on what you put in. When I was at Leo, I’m thinking these guys were authority figures. Whatever they said, you did, no matter what.

Awakening

Leo was deeply embedded in the community. Even so, going there was certainly an adjustment for Mr. Dwyer. As the seventh in his family, he had the perspective of somebody recognizing a rapidly changing world. Looking back at the start of his time at Leo. Mr. Dwyer says he suffered from a variant of ADD, or attention deficit disorder. Needless to say, in the early nineteen-sixties, that kind of learning disability did not exist in anybody’s consciousness.

“When I was at Leo, I think it was still the majority Brothers. I’d say maybe thirty to forty-five percent were younger ones. I couldn’t remember any of them being Chicago natives; a lot came from East Coast, especially Boston, and a couple came from Michigan. From the time I was at Leo, I maybe had three lay teachers. It wasn’t really my doing. You didn’t choose your classes. You were told what you were taking.

“Leo was intimidating the first month or so. Once you got the books, English grammar books stuffed like the Bible, you understood this was serious stuff here. They were very tough on grammar. Some of the Brothers were intimidating. I think I had to work for myself. That’s why ADD was and is a problem. An understanding of that didn’t exist back then. People thought you just weren’t paying attention and whack.

“When I put my mind too it, I could get good grades, and I don’t want to say when I wanted to but when my mind allowed me to. There were teachers I liked and I did well, especially math. There were teachers that took the time and worked with you. I did Spanish, but it was difficult with the conjugations and verbs. My algebra teachers, those were the Leo teachers I was closest to. It’s like work, you might have a terrible day at work, but you always found that one that one thing that made it worthwhile and that’s how it was for me at Leo. There were days I hated going to that school, but you went because you knew there was that one class that made you feel well going there.

“I never had a car, so I walked. When you get to junior or senior years, you’d get guys who drove and you’d get a ride home. Toward the end of my time at Leo, you had Calumet High School. The way I’d walk home meant sometimes going up to 80th Street and Calumet was at 81st. Our dismissal times were supposedly staggered, but they really weren’t so if a group of Leo guys happened to meet up with some Calumet guys, sometimes there’d be fights. I also had a lot of friends at Calumet. ‘Our Lady of Calumet,’ we used to call it because when you flunked out of Leo, that’s where you had to go. Calumet had dances. My grandmother lived across the street from Calumet.

“There were certain times you couldn’t walk home from Leo, you had to be put on a bus. I think that was the first time you realized some big things were going on in Chicago, especially on the southwest side.

Significant deaths

President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas the day after Mr. Dwyer’s sixteenth birthday in 1963. If that death meant the passing of one form, another death struck much closer and registered more immediately.

“My dad passed away in 1964 and he never wanted us to work and just concentrate on school. Everyone thought because my dad was a doctor, we were extremely wealthy. We may have had more things than other people, but I never thought of us as rich. I had an allowance like everybody else, and if it was all gone by Tuesday, I didn’t get it again until that Sunday.

When he passed away, for whatever reason, I decided to take a job at a hospital. My dad was on staff there, and that probably helped me get in. I was only making a buck ten an hour. After school, I had a relative who’d drive me there and then I’d usually walk home or take a bus. I started in the kitchen and worked myself up to a surgical orderly. I might have made two dollars an hour, but it was money and I didn’t have to hit up my mom for money. I think work was more to keep me busy. I was a nonconformist in the sense that if somebody said it has to be done this way, I’d say, ‘I have a better way of doing it.’

Mr. Dwyer’s athletic career also took unexpected detours. Again, it fit a pattern of self-sufficiency and fighting against order. “I thought I’d be able to play basketball at Leo. I wasn’t much for organized sports. My Sabina coach said you have to be careful playing for high school coaches, all they want to do it corrupt you. I played one year on the bantam, but then I went and played CYO and house league ball. It was just a group of guys; we did pretty well in both CYO basketball. We played at 47th and Ashland, but we traveled all over the place. There was a Sabina team for guys in high school. I remember playing a game at this Old Town boys club, which I forget where it was. It was a tough neighborhood, and they didn’t like to see their teams lose, no matter who they were playing. So there was literally a fence that separated the court from the fans. We played in a lot of grammar school and church and these house leagues. There was a house league at Sabina that we played on.

The third death was perhaps the most shocking of all. “Kennedy was killed the day after my birthday. I think I was pretty noncommittal about a lot of stuff. I knew it was going on but it just didn’t affect me. When I left Sabina and went to Leo, I had a group of friends who went to Leo; the girls from Sabina went to either Longwood or Mercy, mostly. A group of guys got into different classes so I got in with people from different parishes. The guys from Sabina were pretty squeaky clean, and the guys I hung around with were into things. I was moving in a different direction. I got into ‘other things,’ nothing illegal mind you, but maybe staying out late or maybe having a beer before they had beer.

“I started hanging around with a group of guys that [crossed] a stratum of ages. My one brother was eighteen months younger, and the rest of the group was some older guys, and myself but they were all within two years of me. We’d hang around a club at Sabina, a place they called the Lot; it was a parking lot. You had the gymnasium on the west side of Racine, that’s where the dances and the basketball and roller-skating were held. There was another area that older kids hung out in, by that I mean people in college. The parish had an influence on all ages. There was another parking lot that had basketball rims, so you’d play basketball over here and baseball over here. There might be twenty guys and girls at any given time, different ages.

“One summer one of the guys that was the most popular guys in the group was shot and killed. That’s when everything changed. Sabina was an aging neighborhood, and some families like ours had an older group and a younger group. Some only had older groups, just the parents. St. Sabina had a real mixture of nationalities. As the older people moved out of the apartments, other [émigrés] nationalities moved in and they didn’t speak English that well. Obviously you had Italians or Irish with their accents or their brogues, but these people walking down the street are speaking Spanish or Polish.

“One summer one of the guys that was the most popular guys in the group was shot and killed. That’s when everything changed. Sabina was an aging neighborhood, and some families like ours had an older group and a younger group. Some only had older groups, just the parents. St. Sabina had a real mixture of nationalities. As the older people moved out of the apartments, other [émigrés] nationalities moved in and they didn’t speak English that well. Obviously you had Italians or Irish with their accents or their brogues, but these people walking down the street are speaking Spanish or Polish.

“My dad was gone, and most of my older brothers and sisters were gone. My one older brother, who was a bachelor, he all of a sudden said you have a curfew. It limited how far east you could go. [The killing] really shook some people up. You started hanging around in different areas. Let’s not the put the blame on any one person. It takes two people to tangle.

“The older ones [in the family] had a very different view of the world. The world they grew up was parochial and homogenous, a ‘white world,’ if you will. I went to Leo during the time of the first group of black graduates. You’d get out of Sabina’s neighborhoods, which was lily-white and you’d get different nationalities. Then you went over to Leo, and it was the first time a lot of people had any contact with any black people.”

It marked an end of innocence. Leo and the neighborhood were now tethered to the rest of the world. The close-knit parochialism of the neighborhood gave way to something much different, fluid, and constant. Thinking back, Mr. Dwyer says, simply, plainly: “Most of the things I think about Leo are good things. The bad things you just kind of shove away.”

New directions

Following his graduation in 1966, Mr. Dwyer confronted new dilemmas and choices. He tried college for a bit, taking classes at Wright Junior College on the west side, but he discovered soon it was not for him. Mr. Dwyer always had a finely shaped sense of what his abilities and interests were

“Vietnam was going on. I could have been drafted, but I happened to be at a family party and one of my brothers-in-law asked me about school and I told him I didn’t like it, and he asked whether I was thinking of going away to school. I said it would have been a waste of money, since I wasn’t that well disciplined. He asked me if ever thought about going into the service. He said I could get a trade I could use afterwards. He said I could be a medic, and that the Air Force was a safe place to go. I got a delayed enlistment and eventually I went into the Air Force in 1967.

“I left Chicago in early November, a Monday and I went down to a base in Amarillo, Texas. It was warm during the day, but at night, you’re out in the middle of the desert and it could be twenty or twenty five degrees. You go through the indoctrination, the shots, you get your head shaved. At one of the orientations, a guy looked at me and he was ordering people to different areas and I asked what was going on, and they said this guy was deciding which career path the different people were going to go. I told the guy, ‘It’s in my contract. I’m going to be a medic.’ He kind of laughed. He said, ‘You’re over six feet tall. You’re going to be a security policeman and you’ll be in Vietnam within a year.’

“I went through basic training. From Amarillo, I was sent down to San Antonio. I went through security police school. I did a six-week training with the Army because the security policemen are going to be sent to Vietnam. My orders sent me to Scott Air Force base outside of St. Louis. I had weapons training. I was familiarized with hand-to-hand combat. I was kind of picked out to be a normal cop, I went into what they call traffic. I was directing traffic in the morning, and then during the day escorting money between the banks. We wore different uniforms. Then I got hooked up with being a general’s honor guard. I spent three years there. When things came up that looked like I might get orders to Vietnam, I’d get sent somewhere for ninety days for temporary duty.

“My godfather, protector or whatever you want to call him, retired. He told me I had a choice: Vietnam or Alaska. You’d go and provide regular law enforcement, just like a regular Chicago cop, because an Air Force base is like a small city. Going to Alaska, you’re going to go to the Strategic Air Command. As a sergeant you’d be marching around B-52 or jet fighters, in sub-zero degree weather. I hate the cold. I said, ‘I’ll go to Vietnam.’

Easter Rising

“On Easter Sunday of 1970, I left Chicago and went to Vietnam. That was an eye opener. I was a sergeant. Before I left, I went back down to San Antonio and trained with the army again: weapons, combat tactics, scenarios and ambushes.

“I took a commercial jet liner operated by the military and flew into Cam Ranh Bay. You saw mountains, and you don’t see those in Chicago. There were fighter jets, helicopters, bombs exploding, and I thought: ‘This was for real.’ I was supposed to stay around Saigon. By the time I left the United States and got to Vietnam, the orders changed and they sent me up north. They sent me to a camp called Phu Cat. The Air Force personnel were not allowed off the base. We had maybe a hundred F-4s that we provided security for. We provided traditional law enforcement, and then also security against attacks and ambushes. We had a K-9 unit.

“I got moved into nighttime security. I was always very fortunate, the way I carried myself, I didn’t get the horrible jobs. I was a desk sergeant. When the sergeant who outranked me would be off, I would take over for him. I didn’t have it bad anywhere. When I went into night security, they made me combat security control, which was control for security for the whole base. We might have had two hundred posts, security policemen with weapons; you had the perimeter of the base, which is three or four hundred yards outside the base. You had to coordinate with the Army and the marines. They were there in case there was an actual attack. The bases were so big that when we did get rocketed or mortared, they very seldom hit a target. The first couple of months I was there, I was pretty nervous, but I settled down. I realized nobody had been killed on the base.

Anybody I ever talk to, I still say that was the best year I had in the service. I made some great bonds with other people in that situation. I never had any problems to quell something.”

Coming home

Mr. Dwyer was not the only member of his family to serve in Vietnam. His oldest brother John, a doctor, was drafted and like their father, served in a mobile medical unit in Saigon. “A lot of the work he did was for removing limbs. When he came back from Vietnam, he went from general practice and became an orthopedic surgeon. That was his practice until the day he died.”

Mr. Dwyer had spent four crucial years, during a time of tremendous social upheaval, in the military. During one leave, he came home to the family house on Ada and discovered that his mother and sister had moved out. During another leave, he returned home during the contentious events of the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Again, Mr. Dwyer was his own man. (During his stint in the military he was fond of listening to music like the Broadway album of the rock musical “Hair,” and the legendary three day music festival, “Woodstock,” art strongly reflecting an anti-war, anti-military stance.)

“I was on leave and dating a girl from Chicago. The older family members were very conservative and establishment. The girl was involved with the protest movement. My girlfriend and my sister got into a big argument, and I remember that was the last time I remember dating her.

“When I got back from Vietnam I was supposed to go to a base in Marquette, Michigan. Somehow the orders got changed again and I was maybe going to get sent to Dover, Delaware, where I used to do temporary duty. I thought that was great. I get back and they’re short of airmen to walk around the planes. Dover is the depository for bodies and they wanted me to do that. I said, ‘Sorry, I had enough of that in Vietnam.’ I decided to take an early out. I left there and flew into Midway.

“My younger brother picked me up, and we met my mother and my sister at a place up on Ashland and 93rd. A terrible storm hit and all the power goes out. It was pouring rain. This was June 17, 1971. We sat there and drank. The lights come back on and my brother was dating this girl and he said: ‘We have to go over to this place on Kedzie.’ He said his girlfriend was bringing one of her girlfriends.

“That’s how I met my wife. Her name is Lynn Tracey. We started dating and I never dated anybody else. We got married in 1973. My oldest son, John, was born in 1976; Anne Marie was born in 1980, and Mark was born in 1988. Early on, I was going to Lewis University, in Romeoville. My brothers were all college graduates, and I told them: ‘I got my college education in the military.’ College is more than just book learning, but common sense but how to mesh with people outside your normal environment.

“My wife’s father and brother were Chicago policemen. They both told me I didn’t want to become a Chicago policeman. I took a test with the state police and took the physical. There are too many issues: you can get shot and killed; policemen have a tendency to go over the deep end on a lot of things. I’ve had friends who were shot and killed. I’ve known some people that have had some real problems. I don’t know I wouldn’t have gone the same way.

“I went to Lewis, got married and that changes everything once you get married because you have bills. I was going full-time and I was working part time for an equipment supplies company. I couldn’t get the courses I wanted for the spring semester, so I decided to go full time with the supplies company. I drove a truck and eventually I was a division manager. I stayed with that until 1976. I had actually started part-time in the summer in ’71.

“I went to work for a liquor company selling wines and spirits on the south side. My older brother was in the packaging industry selling paper products. He hooked me up with a company, and that’s how I got into designing boxes, cushioning materials and I happened to take a bent toward specialty packages, electronic components.

“I ended up in that industry until 1988. There were no more wars, and most of my business customers were military contractors: McDonnell-Douglas Air, Kraft, people that were making weapons systems. No war, no more weapons. I did a couple of stints as a national sales manager doing trade shows.

“There was an opening at the assessor’s office. One of the Leo graduates, Tom Lowery, helped me get an interview. I started there as an analyst to determine whether or not people should get a reduction [on their property tax bill]. Because I know something about computer programming, I went to work in the systems department and data control. I went into management, and I spent 13 years downtown. For seven years now I’ve been out in Bridgeview, at 102nd and 76th Ave. The kids are all gone, and we live in Alsip now.

“Most of the things I think about Leo are good things. The bad things you just kind of shove away. I go to about every third reunion. I went to our fortieth reunion three years ago and saw a lot of old friends. You move on and you have own families and your circles of friends. During the time I was in service, I knew probably a hundred guys, and they went to a hundred different places.

“You run into them at wakes and wedding.”

I am trying to locate Mark Dwyer his phone number has changed. We were stationed together at Scott Air Force Base. I saw his picture at the Air Force Security Force Museum at Lackland Air Force Base this past winter and it reminded me of our friendship. If you can be of any help please contact me. Thank you Mike Stafford 449 16th St. Red Wing MN 55066 (651) 491-7372

Life is a learning process, some do it the easy way, some do it the hard, thanks for the lesson!!