Interviewed and Written by Patrick Mc Gavin 8/09

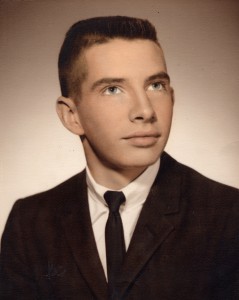

RICHARD DOYLE ’65

Of late a particularly fascinating brand of psychological inquiry has examined the characteristics and personality traits of the first-born. Psychologists have pored over data, behavioral exploration, empirical studies, all designed to understand the motives, tendencies and manner of how a first born of a family thinks, believes or strives toward.

behavioral exploration, empirical studies, all designed to understand the motives, tendencies and manner of how a first born of a family thinks, believes or strives toward.

Conversely the iconoclast, somebody that bends the rules or breaks up the standard narrative, is a significant part of the American experience. The Japanese have a saying that translated believes the nail that sticks out is violently hammered back in. And the very foundation of study, of nature versus nurture, social backdrop, family units, cultural influences, are all valuable tools for understanding how we become who and what we are.

Revolt is an inherent part of the American experience, going back to its founding and the revolutionary spirit that underlined its evolution. It’s natural, even desirable, to find the means to go your own way, against the grain, but at the same time feel a need to be a part of something greater, a piece of the collective whole.

But perhaps a more fundamental belief is simply that lives, though they are inscrutable and examined, must be “lived,” going forward not backward in time. Complications, as they say, always ensue, but that is a part of the puzzle. The life and career of Rich Doyle testifies to all of this. His story is one worth pursuing because every time you think it conforms to something obvious and clear, it is filled with surprise and wonder.

Mr. Doyle explains: “My mother [Virginia] went to Mercy High school. My dad went to Fort Dearborn grammar school and then he went to Leo. His name was James Francis, but everybody called him Jeff. I think my parents met at a dance or maybe they met at a drugstore that my mom worked at, we’re not sure. My grandfather was a soybean farmer in Gibson City; he also raised hens. Any child needs activities when they’re growing up; I was always very active and did things.

“We lived at 8228 S. Elizabeth, in the St. Sabina parish. I’m the oldest of five children. I have three sisters and one brother. I was born in 1947. My father began his career in international banking and he spent most of his life in the credit business. He was a credit manager for a clothing store and several corporations. He taught credit, collections and accounting at Loyola. My mother was a pharmacist. She worked for a lot of privately owned drug stores. My mother didn’t drive; she took the bus every day to 111th.”

Sabina was for many a world of its own, the kind of place that sociologists could have a field day examining the rituals and byways. It was for many a kind of paradise where anything was possible and nothing denied.

“Growing up Sabina was everything, the dances, the roller skating; this may sound kind of crazy but I learned how to dance on roller skates before anything. It was a world unto itself and [Sabina] had everything you’d want.

“I was in cub scouting; I played basketball, I played golf; I played softball; I did everything that kids used to do back then. It was kind of free and open. We spent most of our days at Foster Park. There was always something to do, and we were very inventive. It’s not like today, where there’s not a lot for kids to do.

“I was in cub scouting; I played basketball, I played golf; I played softball; I did everything that kids used to do back then. It was kind of free and open. We spent most of our days at Foster Park. There was always something to do, and we were very inventive. It’s not like today, where there’s not a lot for kids to do.

“We didn’t think about what we didn’t have. In our neighborhood, there were kids everywhere and you could always find a game going on. We played softball in the prairie or the in the street, and we used the sewer covers as bases.”

If Mr. Doyle’s life as a youngster had certain symmetry about it, he nonetheless liked to demonstrate a different side, somebody that was not afraid to show a personal side and had a blessed individualistic streak that manifested itself in different ways, some subtle, some more profound. “After Sabina [grammar school] and it came time to select a high school, there was really no other choice other than Leo. My father instilled in me a deep appreciation for Leo. My father loved the whole concept of Leo high school: the discipline, the Christian Brothers. Leo was a big part of the [Sabina] community; no matter where you went, there were Leo people. Everybody lived in the same neighborhood, even lived on the same block. They’d go to the same grocery store. When you go to school, you’d see in class a lot of the guys that you went to grammar school with or knew from the parks.”

Mr. Doyle had anxiousness about himself as a young kid; he revealed a different desire, one predicated on going his own way and being his own man. One day, a journey outside of the familiar environment of Sabina had a strangely liberating effect on him. The idea of him going to Leo was suddenly throw up into the air by another possibility.

“What happened was I didn’t start high school at Leo right away. There was a seminary school called Tolentine, in Olympia Fields, taught by the Augustinians. I found out about the school because in grammar school at Sabina, we played them in basketball. We went out to play them and I had a friend who was on the seminary team. After the game, they took us on a tour of the school and we had dinner out there. You lived there, on the campus. It was a small school; the freshman class had maybe 40 guys in it. These were guys that were basically studying for the priesthood. If you asked somebody that knew me then, ‘Was Rich Doyle studying for the priesthood?’ They’d say, ‘Fat chance.’ I was the oldest in my family of five. At the time I was ready to pick a high school, I was thinking of Leo, Mendel or Rita. Basically, the allure of being on my own and away from my family was very appealing. Of course, once I was there, it turned very unappealing. The school was miles apart from the South Side. Back then you didn’t have [Interstate 57]. You had to take the regular roads and back streets to get there, and it took a long time.”

The school was some twenty-five miles from his Sabina neighborhood. It was not a radical act of personal rebellion; but it was also not an insignificant move. The safe and comfortable thing was to follow his friends and continue the family line. It was by now the fall of 1962. The world was changing rapidly and significantly. The dynamism of the moment was to follow your own path.

“The biggest reason I decided to go there was to be on my own and get away from home. Tolentine was a very cloistered community. What I learned about myself didn’t occur until I got to Leo. At the seminary school everything was regimented: class, study hall, being a student. At Leo when you had homework or an assignment they told you to bring the books back to school on Monday. I wasn’t as good a student at Leo as I was at the seminary; I didn’t apply myself [academically]. At Leo, I always had the attitude that homework could wait. There were other things I wanted to do. I probably could have been a much better student.”

Mr. Doyle was not allowed to travel home except for the major holidays. Typical of his daring and avid grasp for adventure, he found ways to alter the daily routine. “Even though [the seminary] was a regimented lifestyle, I did have some freedom of movement and I’d go into towns like Park Forest or Matteson. I’d go to the pizza joints or bowling alleys when everybody else at the school was in chapel praying. The priest would be inside the church, and he’d always say, ‘Where’s Doyle?’ I’d be in throwing quarters at the jukebox. I wasn’t a good seminarian. ”The [Augustinians] wore black belts but they weren’t the disciplinarians of the Christian Brothers. Make no mistake, if you messed in around in class, you paid for it dearly. They all thought I was nuts. I guess I never really grasped the opportunity.” Even so, the year away shaped his view of the world around him. He was not exactly incorrigible but he was a free spirit returning home. The gasp of freedom, even if brief, gave him a valuable lesson. He was starting to find himself and assert his will in the world.

seminary] was a regimented lifestyle, I did have some freedom of movement and I’d go into towns like Park Forest or Matteson. I’d go to the pizza joints or bowling alleys when everybody else at the school was in chapel praying. The priest would be inside the church, and he’d always say, ‘Where’s Doyle?’ I’d be in throwing quarters at the jukebox. I wasn’t a good seminarian. ”The [Augustinians] wore black belts but they weren’t the disciplinarians of the Christian Brothers. Make no mistake, if you messed in around in class, you paid for it dearly. They all thought I was nuts. I guess I never really grasped the opportunity.” Even so, the year away shaped his view of the world around him. He was not exactly incorrigible but he was a free spirit returning home. The gasp of freedom, even if brief, gave him a valuable lesson. He was starting to find himself and assert his will in the world.

“By the time I entered Leo, I was getting into going to the beach. At Sabina, there was always something going on. We’d always go to the Leo football and basketball games. With my friends we’d be going to the dances on Friday and Saturday night or Leo basketball and football games. As a young kid I used to be in awe of those older Leo athletes, guys like Jerry Schmitt or Tom O’Malley. I really looked up to them.

“Even though I was small, I was quick and really into softball. The quality of the softball back then was really good. Once during the Father Perez [Knights of Columbus sponsored league] all of these guys were older than I was and they asked me if I wanted to play. I did and I pitched. I’ll never forget it was the first or second inning, and there was a ball hit between first and second base and Bob Cannady flipped it to me as I covered the first base.

“He looked at me, kind of amazed, and he said, ‘Who taught you to do that.’ He was really impressed at how quick I was. It was a really thrilling moment because again, I was used to going to watch guys I played against at Sabina and Leo.

“It really wasn’t that big a transition to go from the seminary school to Leo. The one thing I was very small when I entered Leo. I was probably five-feet, one inch [tall]. I was too small to play football or basketball. I probably weighed a little over a one hundred pounds.

“My first impression of Leo was just absolutely being scared to death of the Christian Brothers. They were a little bit strict. You’d get called up to the front of the class, and if you didn’t do your homework, if you didn’t pass your quiz or have the right answer, the Brothers asked you to bend over and you’d get punished [physically]. Also, I was prepared for how the Christian Brothers acted because in grammar school, the Dominican nuns taught us and they were just as tough and unbending. For the Christian Brothers, discipline was everything and there was no way you could do or get away with what kids do today. I know, I’ve done some teaching and lecturing and talked to kids and there’s no way we could get away with what they do now.

“There were a few lay teachers. We probably didn’t realize at that time that there were not going to be a lot of people that were going into the Brotherhood. The brothers were literally started dying off. So you started to see more and more lay teachers; it seemed like most of them were sports heroes in college or people that distinguished them in many ways. The thing is most of them were just as mean as the brothers.

“I didn’t really like any of the classes. I didn’t apply myself probably in the way I should have. If I had been a bookworm, like some people, I could have graduated near the top of my class, but I didn’t, in part because I was somewhat rebellious of authority and wanted to do things on my own terms. Socially, I connected to both Sabina and Leo because there were so many Sabina people that went to the Leo, so the two were almost interchangeable, the community center, the dances and stuff like that.”

His personal nature was not simply to flout authority. He was drawn to a certain brand of independence, personal and financial. It paid considerable dividends. “I walked to and from Leo every day. The thing that my mother always told her friends was how proud she was that started work at a very young age and that I always paid my own tuition. I had a paper route and I caddied at the Beverly Country Club. If you got five dollars for eighteen holes, that was considered a lot of money. You’d start about nine or ten in the morning and probably go until five. For eighteen holes, the course paid you probably two dollars and fifty cents and then you’d hope to get that same amount in a tip.

“I was always very proud of the fact that I didn’t have to burden my parents with tuition; I started working at an early age. I paid the year’s tuition at Leo, which was one hundred and ninety-six dollars.”

If he was too small for football and basketball, he found something more suitable to his particular talents. It was, like a lot of things he endeavored toward, somewhat unconventional. He was a member of the Leo bowling team. “One of my classmates was on the team, and he got me into it. We use to bowl over at 79th and Troop. You threw against other teams. If you were a good bowler, you were part of the traveling team. I was never a good enough bowler for the traveling team. Some of these guys were incredibly serious about bowling. There were guys that spent all of their childhood years in different bowling establishments. I was at best maybe a once or twice a week.”

If he was too small for football and basketball, he found something more suitable to his particular talents. It was, like a lot of things he endeavored toward, somewhat unconventional. He was a member of the Leo bowling team. “One of my classmates was on the team, and he got me into it. We use to bowl over at 79th and Troop. You threw against other teams. If you were a good bowler, you were part of the traveling team. I was never a good enough bowler for the traveling team. Some of these guys were incredibly serious about bowling. There were guys that spent all of their childhood years in different bowling establishments. I was at best maybe a once or twice a week.”

If his return was somewhat metaphorical, it did not lessen his need to exist on his own terms. “I had an independent streak. I rebelled against my parents at times. The people I was hanging around with, I wanted to do what they were doing. I wanted to be free and be on my own authority. If my parents said I couldn’t do something, I rebelled. I just got back from California on a trip with my sister taking this antique furniture from my parents.

“I’m 62-years-old now and I realized I’m the kind of person I became because of my background and how I grew up. I was not only the first born in my own family, I was the first of my grandparents’ grandchildren and they kind of spoiled me. I don’t like the way they spoiled me. We had five kids in our family and my dad’s sister had six kids, so there were 11 grandchildren and I was the oldest.

“My grandparents really doted on me and I’m sure [subconsciously] I rebelled against that and the all the attention. I didn’t think I really wanted to be that way because my siblings were probably jealous and that bothered me. It made me feel sorry for my sisters and my brother for the way my grandparents [favored] me. Everybody in my family has excelled in their way and they have done things where they distinguished themselves.

“Like I said, I had a paper route, delivering the Southtown Economist and the Daily News. I caddied at Beverly Country Club for five years. That’s where I learned my interest in golf.

Class of 1965

The world order was changing rapidly. Revolutions in China and Cuba and the military expansionism of the Soviet Union in Eastern Europe created a stark conflict of East and West, of democratic capitalism and Eastern bloc hegemony. At the start of the Nineteen-sixties, the tumult was everywhere, the Big of Pigs, the construction of the Berlin Wall, the Cuban Missile Crisis.

On Nov. 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. “I was in English class when the announcement came across the intercom. We were sitting in Brother Carr’s English class and we were just absolutely stunned. We were all given time off school and sit on the floor of the living room and watch the funeral.”

Three weeks before the death of President Kennedy, the two rulers of South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem and his brother Nhu died in a military coup. The continual political and military unraveling of South Vietnam deepened the extent of American military involvement, leading to a widening conflict that mandated increasing number of military service personnel. By the time of Mr. Doyle’s graduation from Leo in 1965, the American military had upwards of half a million men stationed in southeast Asia.

“I never thought about going to college. So when I graduated from school, I got drafted into the army. I did my basic training at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. I was fortunate enough to go to specialized schools. I spent two years in the Army, one year stateside and became. In Vietnam I was a radio operator, even though I’d never been to a signal school.

“I love my country with a passion and my military service and I’m extremely proud of my military service. That’s something that nobody can ever take away from me. My father was in the army and he served at Omaha Beach. The expression ‘Greatest Generation’ didn’t come until years later. When they coined the term baby boomers, everybody knew what they referred to, the offspring of the members that served in World War II. We were part of a special generation as well. There was a tremendous amount of upheaval in the country, but those who went into the military were also part of something very important.

“My father went to the officer candidate school. When I first went into the Army I was having hard time because of the way I was being treated by the drill sergeant in basic training. I called my Dad up and I told him I didn’t like this and that they’re kicking our ass. He told me, ‘That’s their job, to mold me into a man.’ I’ll never forget what he said. He told me, ‘I won’t be very proud of you if you don’t clear up and become the best soldier you can become.’ After that I won the soldier of the month contest. I was promoted four times in two years. I’m proud of what I did and nobody can ever.”

The war ripped apart the country. The bombing campaigns in North Vietnam sparked international protest. College campuses proved the forefront of the growing dissident movement protesting America’s participation in the war. The growing number of American casualties only accelerated the war’s polarization at home. Mr. Doyle spent a year in Vietnam during some of its most ferocious fighting, during the time of Tet Offensive, named for the Vietnamese lunar new year in January 1968, a massive North Vietnamese and Vietcong offensive that shifted the battles from the rural countryside to the streets of Saigon and Hue.

The war ripped apart the country. The bombing campaigns in North Vietnam sparked international protest. College campuses proved the forefront of the growing dissident movement protesting America’s participation in the war. The growing number of American casualties only accelerated the war’s polarization at home. Mr. Doyle spent a year in Vietnam during some of its most ferocious fighting, during the time of Tet Offensive, named for the Vietnamese lunar new year in January 1968, a massive North Vietnamese and Vietcong offensive that shifted the battles from the rural countryside to the streets of Saigon and Hue.

Mr. Doyle strenuously disputes the perception of the war as a lost cause. “General [William] Westmoreland and General [Creighton] Abrams should have been allowed to run the war instead of the politicians. I do not believe what the historians say that we lost the war, or that we should not have been there. We weren’t allowed to win it.”

After his two-year commitment neared its end, Mr. Doyle was faced with a difficult decision. “My commanding officer told me I should re-enlist because he thought I was a very good soldier. I just decided against it because I missed my family and my friends too much and I wanted to go home. I left as a specialist fifth class, which is basically the same thing as a sergeant.

Civilian life

“My experiences and time in Vietnam certainly influenced my political beliefs. At the time that I first entered the Army, I probably was apolitical. The way I vote now is dictated by what I witnessed there. I came back to Chicago on Aug. 13, 1968, a couple of weeks before the protests at the Democratic National Convention, during the riots, when protesters were throwing bags of excrement at police and other authorities. I’m sure that also formed some of my own beliefs. That’s probably why I became a Republican.

“I got a job working down at the Board of Trade. I had some health issues that developed from working there, and I just realized it wasn’t worth it to continue doing that. I spent ten years down there. I got into politics. I did canvassing, grunt work, basically, and I worked for people. I never voted nationally as a Democrat, but Chicago is obviously a Democratic city and that’s what you work for if you’re involved in local politics.

“Since 1983 I’ve been involved in Veterans Affairs, particularly the issue of raising money for hospitals and improving the medical care for veterans. I don’t think the federal government does enough to take care the veterans, and they don’t get the quality care and medical attention they really deserve.

“I quit playing softball some time ago during a game at Kennedy Park. Some huge, three hundred pound guy stepped on and crushed a bone in my hand. Mostly I play a lot of golf. I’ve had four holes in one. I’m about a ten-handicap. It helps me deal with stressful situations.” (His email address is a play on his golf prowess.)

Mr. Doyle is retired, but he remains active and vigorous. Whatever Happened to the Class of 65 was the name of a Time magazine article turned into a book that tracked the interlocking fortunes of the members of a suburban Los Angeles high school. Mr. Doyle’s only movement was an indirect, even circuitous one. He still knows it is possible to go home.

“I think the allure and the history and the reputation of Leo was always important for everybody that went to school there. Even now I’m a staunch supporter of Leo Alumni Association, and I participate in the fundraisers. I’m proud of what they’ve done with the students right now, many of whom attend on scholarship supported by the alumni association that still support the school.”

Speak Your Mind