Interviewed and Written by Patrick Mc Gavin 5/09, Edited by Larry Lynch ’75

The 19th century Irish illustrator Henry Doyle (1827-92) created designs that sharply evoked the national mood and daily activity of Ireland. The wanderer is central to that myth. The sense of escape and adventure is a natural, inevitable part of the Irish experience.

One of his most important drawings is titled, plainly, “Emigrants Leave Ireland,” showing a young extended family, a father and mother, flanked by their children, waving solemnly as the large and impressive ship docks harbor. The look of the father is plaintive and filled with sorrow. The mother is devastated, her body coiled and distraught, her face buried in her hands, as she is unable to watch her grown son depart for a better life.

The “Irish Diaspora,” those of Irish ancestry that alighted out for other parts of the world, is now estimated at some 15 times the number of Ireland’s current population. Irish history is an intensely bittersweet one, ruptured by turmoil, occupation, famine and the horrors of the 11-month civil war that ripped apart the fabric of the country from 1922 to 1923. Many Irish sought a better life elsewhere, one unencumbered by the country’s tragic past.

In departing the home country, many didn’t “leave,” they only resettled and yoked together the best and most beautiful parts of the country. A great many, like Mary (Molly) Corcoran and Michael O’Malley, wound up in their own Irish “island,” of Leo and St. Sabina parish. They inculcated the best of the Old Country, of the familiar, the profound, the music, the language and made it an essential part of their first generation offspring.

In departing the home country, many didn’t “leave,” they only resettled and yoked together the best and most beautiful parts of the country. A great many, like Mary (Molly) Corcoran and Michael O’Malley, wound up in their own Irish “island,” of Leo and St. Sabina parish. They inculcated the best of the Old Country, of the familiar, the profound, the music, the language and made it an essential part of their first generation offspring.

In departing the home country, many didn’t “leave,” they only resettled and yoked together the best and most beautiful parts of the country. A great many, like Mary (Molly) Corcoran and Michael O’Malley, wound up in their own Irish “island,” of Leo and St. Sabina parish. They inculcated the best of the Old Country, of the familiar, the profound, the music, the language and made it an essential part of their first generation offspring.

That is the world, the cultural atmosphere, that Tom O’Malley was heir to upon his birth in February of 1940. The Depression raged and America was about to enter the frightening world wars of Europe and the Pacific. Coach O’Malley has had the most professional distinguished of lives, success at every level he has coached, but his dovetailing identities of student, athlete, husband and father are indelibly shaped by his formative years as a first-generation Irish-American who grew up in the halcyon moments of St. Sabina.

Coach O’Malley was the second born in his family, following his brother John. His sister Maureen was the family’s youngest. “I was born in 1940 and we lived at 79th and Green, a block away from Leo, but we moved to St. Sabina when I was a year old, so I don’t have a lot of memories of the first house we lived in,” he said. St. Sabina was a paradise, particularly for the newly arrived, the émigrés desperately trying to both fit and assimilate but also retain and cherish their Irish identities. “I stayed at St. Sabina until I was married,” he said.

away from Leo, but we moved to St. Sabina when I was a year old, so I don’t have a lot of memories of the first house we lived in,” he said. St. Sabina was a paradise, particularly for the newly arrived, the émigrés desperately trying to both fit and assimilate but also retain and cherish their Irish identities. “I stayed at St. Sabina until I was married,” he said.

“St. Sabina was a great place. It was a basketball haven. Other schools didn’t have a gym, and we had a gym. I loved to play basketball, and it was like an ‘Old Irish’ ghetto.”

Origins

“My dad was from a little town near county Mayo. My mother was from the center of the country. I’ve only been to Ireland once myself, but I visited both places and they were both terrific, quaint small towns.

“My mother came to Chicago when she was 14, and my dad came here when he was 16. She was always referred to as Molly, but Mary was her birth name. My dad’s name was Michael. They came here in the early 20s, during the Roaring Twenties and then into the Depression.

The fathers of most of the neighborhood kids did traditional jobs: cops, fireman, train conductors and the like. Coach O’Malley’s father was a different man, a kind of break the rules iconoclast. “My dad was quite an entrepreneur. He opened up a series of drinking and eating establishments, at 87th and Halsted, 87th and Vincennes, and other places on the South Side.”

At the end of the First World War (1914-18), the “temperance,” or anti-alcohol movement, gained sufficient strength and political clout in the United States to help pass a series of state initiatives that banned the consumption of alcohol. Despite President Woodrow Wilson’s veto, the 18th amendment passed in 1919. Known formally as the Volstead Act, or the National Prohibition Act, it made into law the banning of delivery, consumption or possession of alcohol.

At the end of the First World War (1914-18), the “temperance,” or anti-alcohol movement, gained sufficient strength and political clout in the United States to help pass a series of state initiatives that banned the consumption of alcohol. Despite President Woodrow Wilson’s veto, the 18th amendment passed in 1919. Known formally as the Volstead Act, or the National Prohibition Act, it made into law the banning of delivery, consumption or possession of alcohol.

The states and federal authorities lacked the physical means to enforce the laws, creating in turn a vigorous underground black economy for the dispersal of alcohol. Running afoul of the law was widespread, but it was also a dangerous way to make a living.

“My father was a lot of things. After the Depression, he got out of [the alcohol business] and became a [building] contractor. He got into cement mixing, became a contractor and after that got into trucking. It wasn’t always that prosperous.” The October 1929 stock market crash that triggered the Depression carried lasting consequences.

“There were times during the Depression, I had an aunt who lived downtown at a hotel and she had to bring food home for us. Those were tough times for a lot of people,” coach O’Malley said. The family had at its resources the generosity and social cohesion of the neighborhood, many of them also first generation, what coach O’Malley fondly calls the “Old Country Irish.” In Sabina, families took advantage of the mobile factories that grew vegetables, fruits and other produce. Neighbors shared the yield. It was just another social factor that brought the community together, a shared bond.

Growing up Irish on the South Side

“I grew up on a block, there were 115 kids on the block and so you always had somebody to play with. Without a doubt, you didn’t leave the neighborhood much. With Jerry Schmitt, we probably started playing softball when we were probably five. There’d not only be the Old Country Irish, but we’d be out to eight, nine, ten o’clock at night, you didn’t have to worry [about your safety] because there’d always be another parent out on the front to look out for you. It was inventive era rather than today where everybody is glued to a [television], or the [electronic] gizmos that people walk around today playing, we grew up making up our own games.”

we probably started playing softball when we were probably five. There’d not only be the Old Country Irish, but we’d be out to eight, nine, ten o’clock at night, you didn’t have to worry [about your safety] because there’d always be another parent out on the front to look out for you. It was inventive era rather than today where everybody is glued to a [television], or the [electronic] gizmos that people walk around today playing, we grew up making up our own games.”

His parents were old-fashioned Irish who maintained a near religious devotion to the sanctity of education. Coach O’Malley learned at a precocious age how vigilant they were about school. “I actually started grade school at Sabina when I was just five-years old. My parents were Old School Irish and they thought the best way was to get into school as soon as possible and get started.” For the emerging young athlete who adored football, basketball and softball, the move meant was probably a drawback athletically. All of his friends, like his best mate Jerry Schmitt, were at least a year older and a little more physically developed.

Coach adapted quickly and proved his mettle. He was a natural athlete who took great satisfaction in showing his talent and skill. The American involvement in World War II finally unleashed a sluggish economy and created new opportunities, particularly in his father’s new interest in construction. Conflict was probably inevitably between Irish émigrés and their first-generation children. The fact that so many young American children gravitated to sport and competition was sometimes difficult for their parents to fully understand.

“My brother John ended up going to St. Rita and he was a pretty good football player,” coach O’Malley said. “He played there a couple of years, and then my mother made him stop because she didn’t want to get him hurt. The coach at St. Rita was not very happy about it. The guy who was coaching there actually came over to the house and that sort of thing was very unusual.”

The family trumped everything in Irish culture. “Growing up we always had family members living with us, whether it was my mother’s sisters or family from my dad’s side,” he said. It was the coach’s cousin, a star football player at Mount Carmel that initially caught his eye about going to school there. He played on the dominant Caravan football teams from 1949 to 1951. His exploits certainly captured the coach’s attention.

The family trumped everything in Irish culture. “Growing up we always had family members living with us, whether it was my mother’s sisters or family from my dad’s side,” he said. It was the coach’s cousin, a star football player at Mount Carmel that initially caught his eye about going to school there. He played on the dominant Caravan football teams from 1949 to 1951. His exploits certainly captured the coach’s attention.

“He ended up going to the University of Illinois,” the coach said. “I used to go to his house and I was very enamored with the things that he used to do. For a while I did want to go there, but then all of my friends were going to Leo, and it was a place I could walk. I lived at 77th and Racine and Leo was at 79th and Sangamon.

“I was probably the only guy there who walked home for lunch every day. It was about a four-block walk, but it was worth it, I got the hot applesauce at the bakery on the way home. My mom used to always have a good lunch, instead of having to wonder what the cafeteria was serving. By the time I was a senior, I used to go Top Notch, have some fries.”

Because he entered school so early, the very young Tom O’Malley entered Leo in the early fall of 1953, a member of Leo class of 1957. He was 13-years-old, about five and a half feet tall and avid for sports, activity and accomplishment. Because of his speed and agility, he regarded football as his best sport. He ruptured his appendix as a freshman, meaning he could not participate in any sports his first year. “I wasn’t able to do a lot because of the injury. I started playing basketball because it was a little easier. In my sophomore year, I always had to work because my father was a great believer in the work ethic.

Coach O’Malley delivered newspapers and worked a second job running a grocery route for a Greek owned store at 87th and Aberdeen. “I always had to leave right after school for my paper and grocery route,” he said. Even so, in gym class, he made an impression with his friends with is quickness and uncanny shooting ability.

Leo Advocate

“The great thing about living in the neighborhood and going to Leo is that everybody knew you. It was as though you were a celebrity. Everybody knew you because you played for  Leo. Part of the Irish heritage was they knew the Irish Christian Brothers,” he said.

Leo. Part of the Irish heritage was they knew the Irish Christian Brothers,” he said.

That played a crucial role in his father’s allowing young Tom to play sports at Leo. “I was always the first to leave the building because I had my bike tied up outside, which I used for the grocery and paper route.

“Brother Coogan met me and said, ‘Tom, I think we have to go up to the gym. A couple of your friends have told me you’re pretty good at basketball.’ I remember saying to the Brother: ‘I respect you a whole lot, but my I respect my father even more so. My father wants me to work.’

This amazing thing happened. That night, as we were sitting down to have family supper, the phone rings and it was for my father. Brother Coogan had spoken to this Irish Christian Brother who was from the same part of the old country as my father. He told my father that he asked me to go up to the gym and I didn’t go up there because I had to work. The next thing that happens, my father walked back in the kitchen and said: ‘Tom, why don’t you do what the Brother tells you to do.’

“Ever since that time, I had no problem going up to the gym and playing. I just changed my route to do the paper a little later or changed the grocery route to get it done at different times.”

Catholic and Public League basketball was divided for nearly 80 years by two divisions: lightweight and heavyweight. Regardless of skill level, any player under 5-feet, 8-inches, was automatically assigned to the lightweight teams. By the time young Tom was a junior, he was right at the cut off point, straddling the line around 5-9. “By the time I was in school, they raised it an inch and you had to measure up to 5-feet, 9-inches,” coach O’Malley said. He played in the lightweight class his junior year, and he was thrilled by the speed, intensity and ferocious competitiveness of the games.

Catholic and Public League basketball was divided for nearly 80 years by two divisions: lightweight and heavyweight. Regardless of skill level, any player under 5-feet, 8-inches, was automatically assigned to the lightweight teams. By the time young Tom was a junior, he was right at the cut off point, straddling the line around 5-9. “By the time I was in school, they raised it an inch and you had to measure up to 5-feet, 9-inches,” coach O’Malley said. He played in the lightweight class his junior year, and he was thrilled by the speed, intensity and ferocious competitiveness of the games.

“We only lost four games the whole year, and they were all to De La Salle, and they didn’t lose a game that year. I came in right there and probably grew two inches my junior year. I didn’t even try measuring in my senior year, and I just played heavyweights. Lightweight was a much different style than what the heavyweights played. It was a very fast, motors speed style with people really flying all over the court. You usually had a couple of football players who were [short] but strong and they provided some size and strength to the team. Also, the average size of people was not as big back then as it is today.

“My senior year, our heavyweights were pretty good, we had a positive record, but it was nothing compared to the lightweights. We lost probably six or seven games and they didn’t lose any that year. People sometimes would come to the lightweight games and then take off a little early for the heavyweight games, just because the style was probably more interesting to watch.

Brother Coogan’s intervention with his father created a natural and immediate bond with the young man. Looking back on it, Brother Coogan’s paternal style was a radical departure from many of the other Brothers. Their quick tempers and often physically aggressive manner often drove young Tom to wonder if some of them were outright off-balance. The dominant coach at Leo was Jim Arneberg, the football and basketball coach, a famed Leo graduate and a dominant starting lineman on the 1941 Prep Bowl championship team that destroyed Tilden 46-13 in front of nearly 100,000 people at Soldier Field.

from many of the other Brothers. Their quick tempers and often physically aggressive manner often drove young Tom to wonder if some of them were outright off-balance. The dominant coach at Leo was Jim Arneberg, the football and basketball coach, a famed Leo graduate and a dominant starting lineman on the 1941 Prep Bowl championship team that destroyed Tilden 46-13 in front of nearly 100,000 people at Soldier Field.

Brother Coogan was young Tom’s first mentor. Because of his responsibilities with the football team, Brother Coogan worked first hand with the boys in Arneberg’s absence. Brother Coogan was exceptionally knowledgeable about the game, and his innovative offenses and strategies for attacking the other team’s vulnerabilities played a major role in coach O’Malley’s early development. By contrast, coach Arneberg made a different impact. Coach Arneberg was a former Marine who believed in teamwork, selflessness and honor. Everything was subordinate to the team.

“He was more of a football coach, but he was somebody you respected. If anything, Jim taught us more about being men and about being a strong individual and person than anything having to do with basketball.” They became close after coach O’Malley’s graduation from Leo, and their long conversations about approaches and ideas of coaching had a significant impact on the young coach.

College

Coach O’Malley did not put much emphasis on college. He briefly entertained the idea of going into the seminary. He also had interest from Loyola and DePaul. A different school caught his eye. Loras College in Dubuque, Iowa was a highly regarded Catholic liberal arts school where several of his friends were already enrolled. “I never even visited there before I made the decision, because it was already August. It was a great place, but I’m not sure how much I learned. I learned a whole lot more afterwards.”

Coach O’Malley did not put much emphasis on college. He briefly entertained the idea of going into the seminary. He also had interest from Loyola and DePaul. A different school caught his eye. Loras College in Dubuque, Iowa was a highly regarded Catholic liberal arts school where several of his friends were already enrolled. “I never even visited there before I made the decision, because it was already August. It was a great place, but I’m not sure how much I learned. I learned a whole lot more afterwards.”

Whatever philosophical or personal differences he held toward some of the Brothers for their manner, coach O’Malley quickly learned the importance of the educational foundation Leo provided. “After a while I started to realize there were some really good teachers that were involved there as well. When I left Leo for college, I was as well prepared as anybody [for the academic curriculum]. English was a breeze in college because you had a double period in English at Leo. My math background at Leo was so strong that I had no problems in English or math right away.”

He made a strong first impression at Loras, playing well for the basketball team. Interestingly, if basketball provided his early direction, it became a source of disillusion at Loras. “I thought I was better than I was playing,” he said. He was also upset over what he thought was the school’s reneging on promises about financial help. Unhappy at what he considered the inferior knowledge and coaching ability of the staff at Loras, young Tom stopped playing organized team ball and concentrated on his academic load.

He played intramural football and played basketball games organized by the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU). “I played a whole lot of AAU ball with guys that were probably better than the players at Loras. These were guys that sort of barnstormed through Iowa and the rest of the country. When I started at Loras, I was doing pretty well, but it just wasn’t the right fit for me.”

the players at Loras. These were guys that sort of barnstormed through Iowa and the rest of the country. When I started at Loras, I was doing pretty well, but it just wasn’t the right fit for me.”

He alternated school and work. He took two full years off to help his family out financially. He worked for two years at the Chicago Water Company and made excellent money. “I came back and became more serious as a student. My whole life kind of changed from there.

Teaching and Coaching at Leo

It took him six years to complete his graduate work at Loras. Even so, he was just 22-years-old and again ready to light out in the world. At Leo, Brother Coogan remained his friend, counsel and advocate. At Easter 1961, young Tom returned to Leo and was playing basketball with a group of students at Leo. “I went up to [Brother Coogan] and said, ‘Brother, I hear they’re opening up St. Laurence and Brother Manning, who I knew from Leo, was going to be the principal. I said to him, why don’t you get me an interview with Brother Manning and see what they might possibly do athletically.

“About three days later, I get a letter in the mail. It’s a contract. It said, ‘Tom, sign this, you’re working at Leo next year.’ That was my hire at Leo, no interviews or anything.”

His father pointed out to his $4,200 salary was about a 40 percent drop from what he was making at the water company. It hardly mattered. A coach had found his métier.

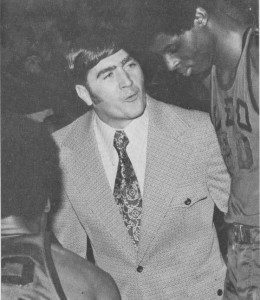

Coach O’Malley taught Spanish, economics and history at Leo. He founded the baseball program. His enduring achievement was his basketball success. He transformed Leo into a national power. He won 288 games during his time at the school, including a school record 34 victories in the magical 1972-73 year. He played an instrumental role in altering the cultural perceptions of Catholic League from a football dominated one to one that also excelled at basketball.

Catholic League basketball was its own universe, typified that it remained wedded to the lightweight/heavyweight division and remained outside the purview of the Illinois High School Association (IHSA). “Anybody that was any good or had talent from the South Side wanted to come to Leo and play basketball,” coach O’Malley said. The Lions dominated the Catholic League. Led by the great Tony Parker, the Lions stormed through the league in 1973.

Catholic League basketball was its own universe, typified that it remained wedded to the lightweight/heavyweight division and remained outside the purview of the Illinois High School Association (IHSA). “Anybody that was any good or had talent from the South Side wanted to come to Leo and play basketball,” coach O’Malley said. The Lions dominated the Catholic League. Led by the great Tony Parker, the Lions stormed through the league in 1973.

The year before, the IHSA adopted the controversial measure of eliminating the single-class state playoff format in favor of a now two-class format. Unlike the Catholic League, the Chicago Public League schools participated in the IHSA state playoff tournament. The classes were divided by class size, schools of 750 students and higher automatically assigned to the Class AA. Because they had open boundaries, all Chicago Public League schools were automatically assigned to the larger AA class. In 1973, Leo easily captured the Catholic League title.

For once, Leo’s great neighborhood rival was neither Mount Carmel nor St. Rita. It was the Public League power Hirsch, located at 7740 S. Ingleside. Behind its two great star Rickey Green and John Robinson, Hirsch beat New Trier West to win the Illinois state high school state championship. Historically, the Public League and Catholic League teams played each other in the basketball equivalent of the Prep Bowl. Because they won the state title, their coach Charles Stimpson, elected to forego the game against the Lions. “I went on with [Channel 2 sportscaster] Brent Musburger to get them to agree to play the game, but they didn’t want to,” coach O’Malley said. “The game would probably have drawn 15,000, but I don’t think Mayor Daley wanted to risk something [violent happening].”

The Lions played for the national Catholic championship in suburban Maryland, where they lost to Washington D.C. power DeMatha, its all-American forward Adrian Dantley and legendary coach Morgen Wooten.

Leaving Leo

In the aftermath of the magical year, coach O’Malley was inundated with offers to coach at the college level. He and wife Carol had three small children, ages five, three and one. “I was not going to move my family around the country just so I could say I was a college coach,” he said. A year later, with a job from a suburban school that offered better pay and improved benefits, Coach O’Malley made the difficult decision to leave his beloved alma mater.

He coached at Reavis for 11 years and Evergreen Park for 14 years. “They were great schools and terrific kids, but we didn’t have the talent and skill level I had at Leo,” he said. “At Leo I could go out and find the talent.” In 1997, coach O’Malley was named the coach at St. Xavier. In 11 years, he has won 75 percent of his college games (283-99). He has posted 11 consecutive seasons of 20-wins, the benchmark for success in high school and college coaching. According to St. Xavier records, he has averaged 26 wins per season over his 11-year collegiate coaching career.

He remains forever tied to Leo. Many Leo fans and graduates attend St. Xavier’s home games. His sons Tom and Mike are graduates of the school. (He and his wife also have a daughter, Carrie. Their 13th grandchild is expected at any moment.) A prominent student, athlete, teach and coach, he is a member of Leo’s Hall of Fame. He is looking forward to coaching for several more years. Reflecting on his life and career, he says, plainly: “I never had a bad time coaching.”

Speak Your Mind